A 2005 New York Times article credited the architect Norman Jaffe, who lived in Bridgehampton until his death in 1993, with pioneering the “design of rustic Modernist houses in the Hamptons.” Yet his houses, despite their significance in the architectural world, are largely unprotected. Even his own house was demolished after his death.

And last month, another Jaffe house, this one at 100 Further Lane in East Hampton Village, met the same fate.

Happy Wife, a limited liability company that owns the property, paid a $1,000 demolition fee on May 1, and, by the end of the month, the house was gone. Only a tennis court remained on the three-acre parcel.

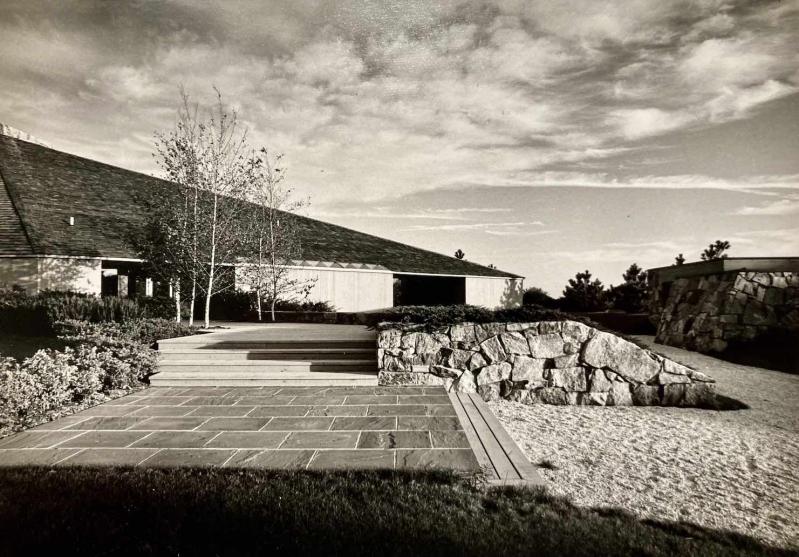

Known as the Stern House, for Joel and Karen Stern, who applied for a building permit to construct it in 1978, the house had fallen into disrepair since Mr. Stern’s death there in 2019.

Still, the listing broker for 100 Further Lane, Rebekah Baker, took pains in a video posted to the Sotheby’s website to highlight the importance of the architecture. Speaking of Mr. Jaffe, she said, “Once he would take an assignment to design, he would look at a site and say, ‘How does this land speak to the design?’ He wanted to celebrate the agricultural vernacular of this area.”

Happy Wife had a different approach. Attached to the demolition permit issued to Drew Katz, its comptroller, was a description of the L.L.C., formed on Jan. 9, 2023, around the time the house was purchased for $15 million (not including an auction premium). “The purpose of the company is to acquire, own, improve, finance, rent, sell, exchange and otherwise deal with and dispose of real estate,” it read in part.

“Everybody says the same thing when something is torn down: Oh, how terrible, it’s so sad. But everybody knew. For over a year, we knew the Stern House was threatened,” said Alastair Gordon, author of “Romantic Modernist: The Life and Work of Norman Jaffe.” Mr. Gordon has been documenting Jaffe’s work for decades and is also working on a documentary about it. The demolition of the Stern House, he said this week, is just the latest instance of a “slow leak” of Modernist houses on the East End.

In the case of this one, he believes a motivated new owner could have built on what was there. “The street facade was incredibly beautifully done, and I think it could have very easily been expanded in the back.” He acknowledge that “The inside needed a lot of work. It was a mess.”

According to Dell Cullum, who was working in the house to remove raccoons during some of Mr. Stern’s last days, even before his death, it was already trending in that direction. “Outside was in fair condition, a little run down. I had to cut holes in the house to catch the raccoons, 17 of them,” he said. “That tells you the size of the floor plan. It’s not common to have two raccoon families living in one house.”

He struck up a rapport with Mr. Stern. “He was such a neat guy. I was happy to know him. He had a collection of about 200 hats. Fine hats from Italy, Spain, everywhere around the world. They were in one of the only spots in the attic the raccoons didn’t get into, his cedar closet.”

When told about the demolition, Mr. Cullum, who grew up locally but has since moved away, said, “It never gets easier to see it happen. It still hurts.”

The only hope Mr. Gordon sees for preserving what remains of these Modernist houses is to demonstrate to municipal governments, and to the public more broadly, that these designs are worth the investments of time and money needed to restore and preserve them.

“It is a shame we can’t save every house, but the village has taken many steps into protecting very old homes, such as the timber-frame homes and homes in our historical districts,” said Mayor Jerry Larsen. “But picking out homes that are 50, 60, or 70 years old is a little difficult. That could be a topic for an expert to bring up as we work on our new comprehensive plan.”

Caroline Zaleski, author of “Long Island Modernism, 1930-1980” and a trustee at Preservation Long Island, said real estate values can make preservation here particularly difficult.

“You’re in a place where the land is so much more valuable, and that’s what you’re bucking against. There has been a weakening in East Hampton Village, or a lack of appetite to designate buildings as landmarks, but the government does have that power. It’s most important to have an owner that will allow for the house to be designated, because they think it’s important for it to remain part of the village’s heritage.”

Mr. Gordon said he had spoken to the architect working for Happy Wife and informally to officials in the village’s Building Department asking for a “heads-up” if a demolition permit was going to be granted, hoping that he could film the process.

“If it’s going to be torn down, I want to document it,” he said in a recent phone call. He had even implored neighbors to let him know if they noticed bulldozers or other signs of impending demolition. He never received those tips.

East Hampton Village transitioned to a new building inspector around the time the house came down. Joseph Palermo is the new chief building inspector, having taken over from Tom Preiato, and he said he has yet to receive plans for a new house at the location.

The next Jaffe demolition Mr. Gordon anticipates is of the Bliss House at 88 Meadow Lane in Southampton. The owner, Orest Bliss, who commissioned the house and had to apply to the village’s architectural review board in 1978 for permission to build the house in the historic district in the first place, applied again to the board in 2021 for a certificate of appropriateness that would allow for it to be torn down.

Though board members were reluctant to approve the “radical design” when the house was built, the 2021 board denied Mr. Bliss’s application, reasoning that the house made a “significant contribution” to the district. (It had engaged Mr. Gordon to do an assessment and produce a report about the house.)

Mr. Bliss challenged the board’s decision in Suffolk County Supreme Court, and a judge found the board’s reasoning “arbitrary” and unsupported by “facts and law” and ordered it to issue the certificate within 10 days.

The village appealed the decision, and while the appeal was still pending attempted to start proceedings to landmark the house (though it did not meet the 50-year age requirement for landmarking), which would prohibit demolition. It ultimately tabled the plan pending the outcome of the appeal.

In March, the Supreme Court’s decision was upheld, and the certificate of appropriateness ordered to be issued. The new owner can demolish the house.

“The problem with municipal governments is they change rapidly and suddenly,” said Mr. Gordon. “So, you have to have private citizens who just, you know, take it on that they’re going to kind of be watchdogs for that kind of thing.”

“Unless there’s a really strong preservation core that’s involved in local government, who really cares about it and is making an effort to be inclusive of late-postwar and late-20th-century stuff, then it’s not going to happen. It’s going to continue until there’s almost nothing left like that.”