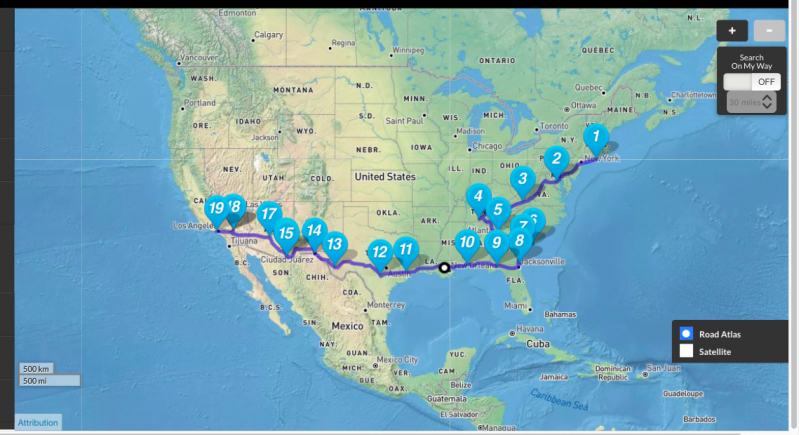

Not knowing in February 2020 that isolation would become a mandated way of life, I chose to go on a solo road trip across the United States. I had been kicking the idea about for a while, spurred by a burgeoning desire to better understand this monster land that has been home for over 30 years. Having lived on four continents and traveled to almost every corner of the world, it occurred to me that I was utterly clueless about the interior of America. I knew all about its many myths but what about the realities? I needed to get to the heart of Americana and meet its people -- flaws, shining qualities, miseries, triumphs, and all.

"I discovered I did not know my own country," John Steinbeck wrote in 1960 in "Travels with Charley," explaining why he drove from Sag Harbor with his poodle, through 38 states, age 58, in the months leading up to the Kennedy-Nixon presidential election. The following are the only parallels I will ever draw between myself and Steinbeck: I, too, was 58 and it was an election year when I hit the road to speak with strangers. Steinbeck's first stop was Connecticut to say goodbye to his son, one of "200 teenage prisoners of education just settling down to serve their winter sentence," he wrote. Mine would be Washington, D.C., where my teenage son was doing time in an institution of higher education.

The nation's capital seemed like a good place to start. Here, after all, is where our political system began its descent into a surreal exhibition of postmodern, anarchistic art. The area is also home to 20 colleges and universities, serving almost 300,000 students each year -- all that wokeness! At American University I chatted with a couple of political science students who could easily saturate a room with their optimism, especially on the subject of social injustices, Bernie Sanders, and a need for a "revolution." Socialism will never win in America. Not now but just wait. Today's disappointed youth may well find vindication by helping to build a future world free of avoidable injustices.

During the 5,000-plus miles I clocked over 25 days, I was drawn to human interaction as if in preparation for this new reality where I swerve around fellow beings.

From D.C. I drove about 240 miles southwest into Virginia, between the ancient peaks of the Shenandoah Mountains to the west and the Blue Ridge to the east. On the outskirts of Roanoke, a group of conservationists and historians working to preserve the natural heritage of western Virginia had been gathered by Liza Field, a writer whose words I came across in The Roanoke Times. I had scoured local newspapers that are still being published across America, looking for real issues that Americans were dealing with. That was before we all started dealing with the same one.

In the Virginia countryside, rapid development is wreaking ecological havoc. The environmentalist group invited me, a complete stranger, for lunch at the Fields' home. Over homemade chicken soup and cornbread they discussed, with sadness but also with great determination, the issues and their efforts. After lunch, we went on a quick tour of the area, which included a drive up Mill Mountain to see the Roanoke Star -- the largest, free-standing, man-made, illuminated star in the world. Under the giant installation, a young couple were in a deep embrace, swaying gently to a slow tune coming from a small boom box at their feet. It was Valentine's Day.

Heading farther west, I overnighted in Wytheville, pronounced With-vull as I was quickly corrected. The town, traditionally Republican, is very low-waged: $7.25 is the minimum. Best known as the birthplace of the spunky first lady Edith Bolling Wilson, the state's oldest hot dog joint, and the only town in America named Wytheville, it recently received a $700,000 makeover. I strolled down the town's newly revitalized center -- basically up one side of a small street and down the other -- around 5 p.m. on a pre-Covid Friday, and I was entirely alone. The newly-installed street-side speakers were playing the Bee Gees' "Staying Alive."

"Are you going to Nashville?" was the usual question whenever I mentioned I was heading to Tennessee. It's a fair question given Nashville's XXL honky tonk reputation, but I wanted to avoid large towns whenever possible. Instead, I headed about 100 miles south to Mulberry, population: 775.

I was told that on my way there I had to see Dollywood, Dolly Parton's home-turned-adventure park in the Smoky Mountains. But I never did because I was so mesmerized by the beauty of the Smokies that I veered off somewhere and lost my GPS and cell service. The Great Smoky Mountain range sits at the southern end of the Appalachian Trail, and the entire landscape is shrouded in a haze (hence the name). I found myself entirely alone in this wondrous, perspiring forest. I have trekked through pine-covered mountains in Bhutan and marveled at the majesty of the Swiss Alps, but I'd never experienced this feeling that everything around me -- the trees, the mist, the clouds, the shoots of new growth -- were there just for me.

Well, for me and bears, and moose, which I'd heard were aplenty. It wasn't until I reached a verdant valley with a house across from a babbling brook that I got out to take photos.

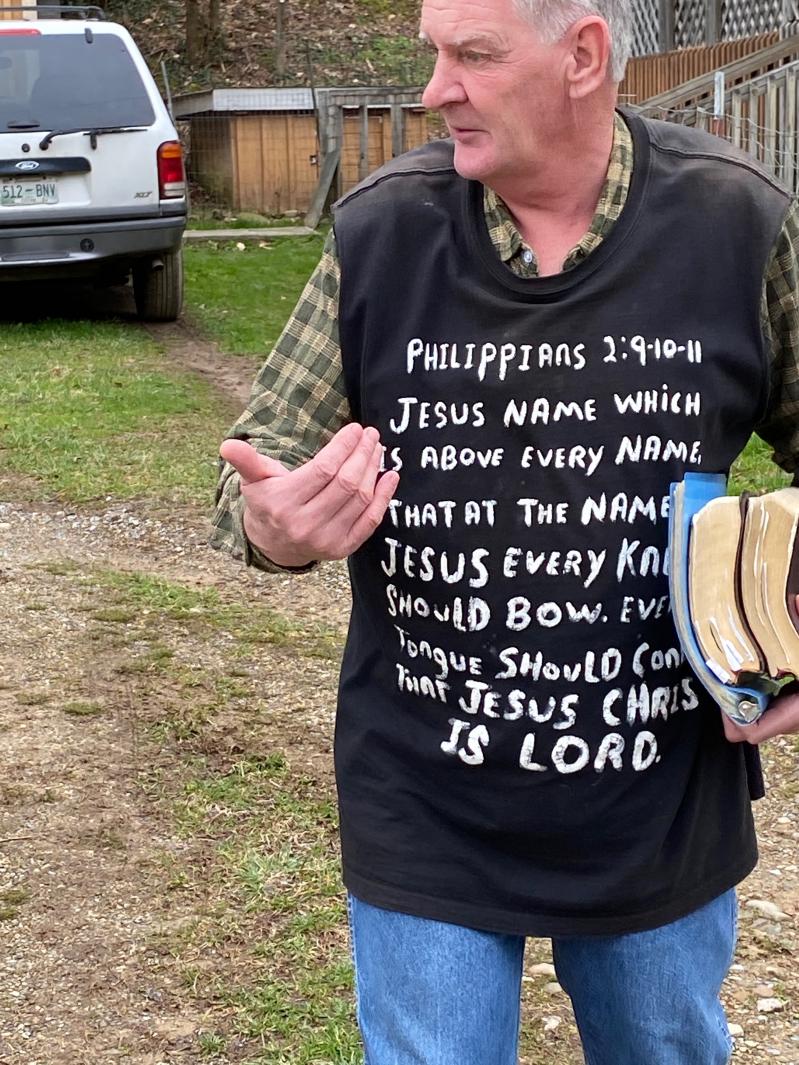

"Hello?" a man said, emerging from the house. "Are you all right? Do you need help?" He was wearing a pinafore with writing on it.

"I'm fine, thank you," I said. "It's so beautiful here."

"Yes, the Lord has blessed us," he said, introducing himself as Jimmy Morrow, a local pastor and native Appalachian. I asked him about the biblical verse on his pinafore and he told me he was getting ready to deliver a service at the Edwina Church of God in Jesus Christ's Name. I was in what's known as "the buckle of the Bible Belt."

When he heard I was from England, he told me he's been in a BBC documentary and written several books. About what, I asked.

"About the command of Jesus Christ," he said. "Our faith in these parts is strong because we fear no one except God." Later, Google told me that Mr. Morrow is one of the few serpent-handling preachers left in Appalachia. I watched YouTube videos of him speaking in tongues and handling several venomous snakes, an ancient and illegal practice that goes largely unchecked. When eventually we said goodbye that day, he promised that the good Lord would guide me onward. I thought better of telling him that my God was named Waze.

I clocked well over 1,000 miles zigzagging through the south. In strip-mall-centric Lilburn, Ga., about 20 miles from Atlanta, I discovered BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir, the largest Hindu temple in North America, constructed of more than 34,000 individual stone pieces carved by hand in India, shipped to America, then assembled in Lilburn like a giant jigsaw puzzle, utilizing 1.3 million volunteer hours. What an unexpected and humbling sight.

I had always wanted to see Charleston, S.C., but found Savannah, Ga., far more seductive. Gnarled trees weeping with Spanish moss surround sleepy squares and dignified streets of colonial-style houses. It's a complex place with a dark history of playing a pivotal role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. But today, old Southern money seems to coexist with a largely African-American population, and the town's bustling eateries, such as Mrs. Wilkes Dining Room, where President Obama ate, are full of talk as peppery as the food. So many mystery books have been set in Savannah, including the most famous, "Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil," that one could be forgiven for thinking of it as a murder mystery theme park rather than a youthful, energetic, liberal Southern town, largely thanks to the arts college here.

Driving across an unremarkable stretch of the Gulf panhandle, a highway billboard advertising Vietnamese pho soup was such an incongruous sight that I decided to follow the signs to the Pho Noodle and Kaboodle restaurant. Two truckers were the only others there. My steaming bowl of pho turned out to be deliciously authentic, cooked by a Vietnamese woman from an immigrant family who now owned several businesses and real estate in the area. The American Dream realized in Bonifay, Fla., a pinprick of a town with 2,000 residents. Whitney, my server who told me all this, was a Bonifay native probably in her early 20s. She was fascinated and wistful about my road trip. Then, she perked up and said she was going on her first plane ride in mid-March, to Jacksonville on the East Coast. Her friends, she said, had pitched in to buy her the ticket and she was very excited. I wonder if she ever got on that plane.

At the Oak Alley Plantation Inn in Vacherie, La., about an hour northwest of New Orleans, the antebellum mansion is one of many "big houses" (for slave owners long ago) that still stud the landscape. Oak Alley is now a combination of museum and guest quarters and I stayed the night in one of its eight cottages.

The literature in my room seemed to encourage reminiscing rather than reflecting: "Experience a bygone era in one of the South's most beautiful settings. . . . Learn about southern plantation life before the Civil War. Tour the elegant 'Big House' with a costumed guide who will reveal the stories of the home and its history."

Its history is that of an enormously successful sugarcane plantation where about 125 men, women, and children were enslaved. In the back garden are the original slaves quarters, now a museum with displays including instruments used to harness unruly ones and reprimand small children. In one cottage, all the names and prices of the individuals are listed. Should that be too depressing, frivolity can be found in the cavernous gift shop selling commemorative aprons, spoons, and sugary treats. Or, perhaps, with a visit to the bar for a quintessential mint julep. The mansion can also be rented for weddings and film shoots. What was it that William Faulkner once wrote? "The past is never dead. It's not even past." Apparently it is in Louisiana.

Texas legend had grown in my mind to . . . well, Texas-size proportions, having spent a childhood watching spaghetti westerns and Larry Hagman. I wished I had a month to drive through Texas alone -- it is the largest state in the contiguous U.S., covering almost 300,000 square miles. It seems layered and perplexing.

Luling, a small town along the San Marcos River, was once known as "the toughest town in Texas" because it attracted a rowdy mix of workers who stopped there for jobs on the oil rigs. Today, it's famous for a watermelon seed-spitting contest (in June) and for the reason I went there: the Original City Market BBQ, a down-home smoked meat joint. I ordered straight from the pit master in the back room that's blackened from years of smoking: sausages, brisket, ribs, served on butcher paper, succulent and heavenly. Vegetarians should drive on.

I continued another 450 miles west on Interstate 10, through uncompromising mountain ranges and sun-grizzled deserts that seemed to play on a loop. The sense of space is absolute and endless, broken only by eagles swooping down and a parade of Amazon delivery trucks. We are a nation of shopaholics.

I finally arrived in Marfa, one of the least-populated, most-isolated corners of the U.S. with continuous desert or mountains on its horizon in all directions. This is surely the funkiest village in America. The late minimalist artist Donald Judd moved here from New York City in 1971 and turned it into an art capital of far west Texas. Marfa is still tiny -- barely one square mile and a population of under 2,000 -- but it's alive with American ingenuity. Galleries, gourmet restaurants, a public radio station, a weekly newspaper, and hand-crafted-everything emporiums. It's like Williamsburg in the dessert.

Except for the swarms of U.S. Customs and Border Patrol agents. Khaki-clad and mostly appearing to be of Hispanic origin, the officers hang out with family members and colleagues in the town's restaurants and hotel lobbies. The Marfa C.B.P. station, responsible for 68 border miles between the U.S. and Mexico, sits in an old lumber yard on the main street, right next to the upscale Saint George hotel and a row of galleries.

The C.B.P. also has a partially-tethered blimp, Goodyear-size, as part of its "eyes in the sky" narcotics surveillance. I was told to look out for it as I left Marfa for El Paso along U.S. 90. But I stumbled upon something far more wondrous instead: A roadside plywood tribute to the 1956 James Dean, Rock Hudson, and Elizabeth Taylor film "Giant," which was filmed in the area.

In the U.S.-Mexico border town of El Paso, it was domestic terrorism that made headlines in 2019 when a white nationalist shot and killed 22 people in a Walmart. The town is 80 percent Mexican. I walked to the Paso del Norte Bridge, one of four border crossings between El Paso and Mexico. It was a Friday evening and scores of people were hurrying on foot and in cars to leave the U.S. Hundreds of people do the crossing daily, living and working in these two worlds that seem to depend on each other. The line coming back into the U.S. extended the entire length of the bridge.

"It's about a two-hour wait to come back," said a Mexican-American woman on her way to Ciudad Juarez for the weekend. A transitional shelter was erected inside a chain-link fence under the bridge after dozens of illegal immigrants were captured by border agents a couple of years ago. From the makeshift compound, its residents can probably see the huge metal gateway to the city with the words "El Paso Bienvenidos."

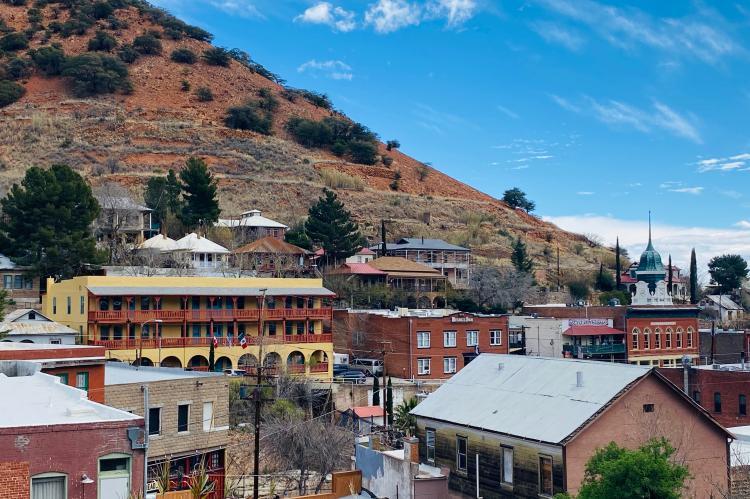

After El Paso came another border town: Bisbee, Ariz., is about 10 miles from the Mexican crossing. As I pulled into a public parking lot in the center of this beguiling old mining town once frequented by John Wayne, the parking attendant smiled as I got out of my car and said, "New York plates! Did you drive all the way?"

The town is an eclectic mix of artists and writers, new-agey eccentrics, old-world charm and, sadly, a visible meth problem. Wandering through a vintage furniture store, I overheard a tattooed and pierced man tell the young woman who worked there that his ear was badly infected.

"Do you have health insurance?" she asked.

"No."

"Just drive into Mexico, man. They'll take care of it for, like, 10 bucks."

The richest country in the world is structurally ill-equipped to care for its citizens, something the pandemic has certainly exposed.

Although Arizona is home to the world's most famous canyon, I headed to another legendary site: Tombstone -- "the town too tough to die." Here, an eight-second gunfight at the O.K. Corral took place in 1881 and continues to keep the town alive. There's a daily re-enactment of the famed shootout that's cringey but fun. And at the many dude ranches in town and nearby, like the Tombstone Monument Ranch, where I stayed, they're milking the Wild West lore for all it's worth, with replica swing-door saloons, shooting galleries, and barn dances. But the cowboy and cowgirl culture felt insular and exclusionary, and despite being surrounded by breathtaking natural beauty, I was happy to ride out of Arizona.

It wasn't until I reached Pioneertown, Calif., on March 4, the day after the California Democratic primary, that the news began shifting away from politics to the coronavirus. A cruise ship near the Golden Gate Bridge had a dozen passengers and crew members who had tested positive, but it still didn't seem like urgent news.

At the edge of Joshua Tree National Park in Southern California's high desert, Pioneertown was built in the 1940s by a group of spaghetti western legends, including Roy Rogers, as an easily accessible film set for their cowboy movies. About 30 miles from Palm Springs and 125 miles from Los Angeles, everything in town is a facade -- literally faux exteriors of saloons and trading posts. But real people live here -- about 350 in the hamlet -- now that the cameras have stopped rolling. The Pioneertown Motel is immaculately designed with 20 Western-theme rooms, each named after a Hollywood cowboy legend. (I stayed in the Gene Autry.) It serves as a weekend escape for "every bearded hipster and his brother from L.A.," according to the hotel manager. Luckily, I was there midweek, and because the weather was still cool, the "snakes and tarantulas aren't out yet," he added.

Then, after three weeks of perpetual motion and crossing 20 state lines, I arrived in Santa Monica, the Pacific Ocean in front of me. I had run out of western roadways.

The great American road trip is no ordinary car journey. When done alone, it's an epic meditation session. The quiet solitude gave me a chance to reflect on my travels and focus on things that are certain in life (good Covid training). Like the physical beauty of place and the gentle magic of small towns. And that of the humanity I encountered along the way. I've decided that Americans are some of the most open, kindhearted people a traveler could hope to meet. And that optimism is deeply embedded in their DNA. I also came to really appreciate, during this trip and certainly in the hellish year since, how precious human contact is. And how far just a little of it can go.