There I was, at my desk beneath the strange Pamela Ornstein dog painting, gazing up at the bookshelves flanking it, and noting that I was newly between novels, always an exciting time.

On an upstate kick, I’d devoured Richard Russo’s “Mohawk,” family stories in a dying town, and William Kennedy’s “Legs,” about Jack Diamond, a gangster’s tale of the Prohibition years, part of his Albany cycle, and a revelation.

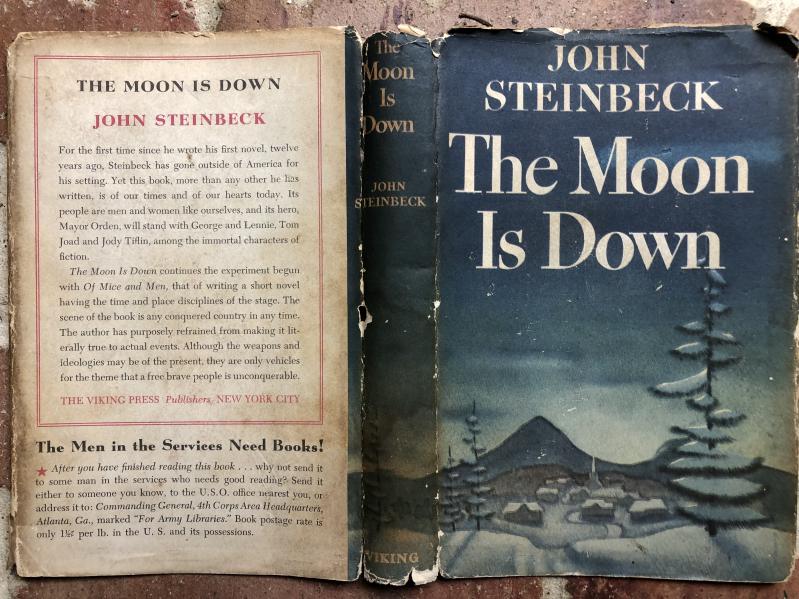

That’s when I spied a grimy 1942 copy of John Steinbeck’s “The Moon Is Down.” Viking Press. An atmospheric Frank Lieberman jacket illustration of a snowbound European village. Just 188 pages. And the author, “Sag Harbor’s own.”

Speaking of strange, it’s a kind of World War II allegory, its setting indeterminate, its players hinted at, in some ways like a play without stage directions, and a play I gather it in fact became. It’s also far more absorbing than that makes it sound.

Not everything needs to be spelled out. Writers of that era tended to leave more to the imagination, which is obvious, say, if you read William Faulkner’s “The Sound and the Fury” with fresh eyes.

Although, as Southern authors go, I fell pretty hard for Eudora Welty on reading her oddball short story “Why I Live at the P.O.” It might be that what I remember most about Faulkner was learning in a college classroom in the early 1990s that in a list enumerating the subjects of English department Ph.D. dissertations, it was Shakespeare and Faulkner at the top, and then a steep drop-off to the rest.

But if Steinbeck was striving for a timeless quality in “The Moon Is Down,” he nailed it. Occupiers and the oppressed. Conquerors either halfway sympathetic or hapless, mostly following orders. Unbeatable guerrilla tactics by spirited natives. Not unlike the colonial American revolutionaries? That’s certainly palatable. But also, you could argue, anticipating the Vietcong and the Taliban.

What’s unleashed can’t be controlled, Steinbeck knew, but still the bombs fall.