Last week my generation mourned the first and only use of the atomic bomb, the creation of which is documented in the feature film about the theoretical physicist Robert Oppenheimer. Aug. 6 and 9, 1945. Hiroshima. Nagasaki. Two hundred thousand dead. Many more injured and sickened by radiation from the bombs. Those events spawned not only the terrifying and wasteful nuclear arms race, but also the modern anti-nuclear peace movement and the environmental movement.

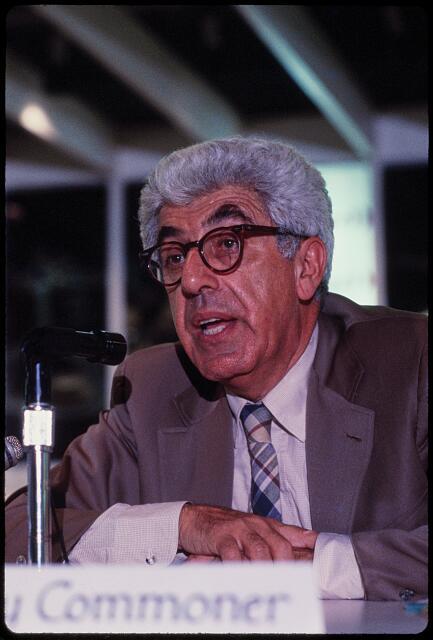

Watching “Oppenheimer” and the follow-up reports in The New York Times about the failure of the U.S. government to properly compensate all the residents of the South and Northwest and Pacific Islands who suffered from not only the Trinity experiment but the more than 1,000 tests that followed, I was transported to the late 1960s, when I met Barry Commoner, who led the scientific and political movement to ban nuclear testing. Those U.S. tests, initially in Nevada, spread atomic radiation fallout across the American West and farther.

Commoner’s Baby Tooth Survey collected children’s baby teeth throughout the region. What they found in those teeth was Strontium-90, which acts like calcium accumulating in teeth and bones, causing cancer of the bone, bone marrow, and soft tissues around the bone. Commoner, a molecular biologist, and his team published a scientific newsletter in the 1950s called Nuclear Information. In the early 1960s the name changed to Science and Citizen. His mission was to take the work of scientists to the public sphere. Commoner’s research on radiation fallout from nuclear weapons testing led to the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963.

When I met Commoner in 1968 he was the director of the Center for the Biology of Natural Systems, or the Science of the Total Environment, at Washington University in St. Louis, where I was a grad student in the sociology department. Nuclear Information had morphed into Environment magazine, where I had a part-time job as assistant librarian — a fancy title for someone who helped organize all the towering piles of academic papers and journals in a room designated for reading.

That’s when I began to read scientific articles about pesticides, as well as air, water, and soil pollution. Of course, that reading room included Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” (1962), about the dangers of DDT while popularizing scientific research on pesticides. “Silent Spring” also proposed the question “Who speaks and why?” So that reading room was my introduction to the environmental sciences and the effort by Commoner’s team to communicate that work to a lay public that was expected to debate what to do with that information.

Meanwhile, Commoner was lecturing widely on not only nuclear contamination, but air and water pollution, as well as the dangers of pesticides and the misuse of phosphates.

By 1970 I was writing and handing out mimeographed leaflets on the Washington University campus, reporting rivers erupting into flames while heaving up dead fish from industrial pollution. I and a large cohort of students were also protesting the Vietnam War. That spring — the same spring of the Kent State University student deaths at the hands of National Guardsmen — Commoner’s portrait appeared on the cover of Time magazine, which described him as the “Paul Revere of the modern environmental movement.”

In April that year we celebrated our first nationwide Earth Day, and Commoner was credited with influencing President Nixon to establish the Environmental Protection Agency and sign the Clean Air Act. My generation, which had lived through atomic drills in school getting under our desks with our hands behind our necks, was mobilizing against a very present war while participating in the launch of a movement that had its roots in a previous war.

The following year, 1971, Commoner published “The Closing Circle: Nature, Man, and Technology,” in which he outlined his four laws of ecology: Everything is connected. Everything must go somewhere; there is no waste in nature. Nature knows best; any man-made change to a natural system is likely to be detrimental to that system. And there’s no free lunch: Exploitation of nature always involves an ecological cost.

The idea that everything is connected in nature didn’t begin with Commoner. In fact, Alexander von Humboldt had revolutionized the scientific community in Europe and the Americas with this idea some 150 years before. But Humboldt had long since been forgotten. We needed a trailblazer to remind us once again.

In “The Closing Circle,” Commoner argued that the U.S economy should be restructured to conform to these immutable laws of ecology. He was the first to introduce the idea of “sustainability” to a mass audience. Commoner would continue to write influential books (“The Poverty of Power” in 1976 and “Making Peace With the Planet” in 1990).

In 1980 he created the Citizens Party and ran for president. Throughout this period he engaged in a very public debate with the neo-Malthusians, largely represented by the work of Paul Ehrlich, who argued that overpopulation was the cause of the planetary crisis of poverty and food insecurity. Commoner countered that capitalism was to blame. Rich countries should help poorer ones to develop, and with that population would decline.

By 2000 Commoner led the Dioxin Arctic Study, whereby he and his team discovered high levels of dioxin in the breast milk of Inuit women living in the Arctic Nunavut. This research identified 44,000 sources of dioxin pollution from the U.S., with the Harrisburg Incinerator in Pennsylvania as a top source.

So what’s the point of remembering Commoner now in 2023? Despite all of the studies, the scientific research, the efforts to interpret that work and engage a broad public, our planet is in even graver crisis than in 1968.

Perhaps we can remind ourselves of those four laws of ecology that Commoner so clearly laid out way back then. As we struggle with the existential challenges of global warming, the climate emergency, a catastrophic collapse of species including birds and insects, the threat of contaminated drinking water systems everywhere along with the disappearance of potable drinking water, we need this reminder.

Suffolk County is now the biggest consumer of pesticides of any county in New York State. We need more research into how those pesticides combine and leach into our ground and drinking water and bays and how they impact human health. We already know their calamitous effects on birds, butterflies, and beneficial insects.

We have the highest levels of nitrogen in our waters in the state.

We lack a functioning public transportation system and affordable housing that would relieve pollution and carbon emissions from cars and trucks.

We continue to squabble over alternative energy projects.

Our zoning and building regulations have somehow allowed for overdevelopment to the detriment of natural ecosystems. And while we have a dedicated core of environmentally conscious citizen activists, government representatives, and journalists, we have a lot of work to do — at all levels, from our federal government to our citizen selves — in the face of our very real planetary crisis.

Commoner never wrote with despair. He knew that hope for the planet came with action.

Gail Pellett is a documentary filmmaker, journalist, and author. She lives part time on Three Mile Harbor in East Hampton.