Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank were two of the three largest banks to fail since 1933. The contagion spread to Silvergate Bank, Credit Suisse, and First Republic Bank. But in sharp contrast with 1933, United States banks are now backstopped by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. That gift to American depositors, and to the U.S. financial system, depended crucially on the management skills of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first Treasury secretary, the former Lily Pond Lane resident William H. Woodin.

Woodin was a staunchly conservative East Hampton Republican who had served for 15 years as C.E.O. of the country’s largest railcar company. He used his money and power to play a key role in financing Roosevelt’s elections. He had the trust of the business community, but he supported Roosevelt because they were friends and both cared about “the little guy.” Woodin served on the board of Roosevelt’s primary charity, the Warm Springs Foundation for polio victims.

Roosevelt reportedly never spoke to Herbert Hoover again after their ride to Roosevelt’s inauguration. Yet it was crucial for Woodin that the Treasury leaders hand on to him their ideas for resolving the crisis. On Friday, March 3, 1933, when Roosevelt’s new team started work in a suite in Washington’s Mayflower Hotel, the financial system was in freefall. Phone calls flooded in like a tsunami. Gold withdrawals were “devastating.” The major stock exchanges, and banks in 38 states, closed down. The financial heartbeat of the United States had stopped.

At 1 a.m. on Saturday, March 4, Inauguration Day, Woodin went with Roosevelt’s “Brain Trust” leader, Raymond Moley, to join Hoover’s outgoing senior staff at Treasury. There Woodin worked on a financial recovery plan with the outgoing Treasury secretary, a New Yorker, Ogden L. Mills, and several other exhausted Treasury officials. Fortunately, Woodin and Mills knew each other well from Woodin’s five years as a director of the New York Federal Reserve Bank. As Moley wrote later, the team became “just a bunch of men trying to save the banking system.” They had “forgotten to be Republicans or Democrats.”

Later that day, in the rain, the U.S. Marine Band played Woodin’s “Franklin D. Roosevelt March,” and then, in his 20-minute Inaugural Address, Roosevelt asked for “broad executive power to wage war against the emergency.” (“The only thing we have to fear,” he said, “is fear itself — nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror. . . .”)

On Sunday, Woodin prepared two presidential proclamations that were ready that evening and issued soon after midnight, calling for a national four-day bank “holiday,” a pleasant euphemism for closing down all the banks. The idea was that at the end of the four days, Congress would convene and vote on a yet-to-be-written emergency banking bill that Woodin brashly promised Roosevelt he would have ready by then. Meanwhile, Roosevelt ordered the “suspension of all banking transactions,” closing all U.S. banks.

On Wednesday, March 8, Woodin handed a draft of the Emergency Banking Act to the congressional technical staff for legislative review. The bill confirmed the bank closings and ended private convertibility of currency into gold or silver. Woodin and Attorney General Homer Cummings briefed Roosevelt on the bill. Roosevelt then briefed congressional leaders, especially Representative Henry Steagall, the chairman of the House Banking Committee, and Senator Carter Glass, former Treasury secretary under President Woodrow Wilson and a key member of the Senate Banking Committee.

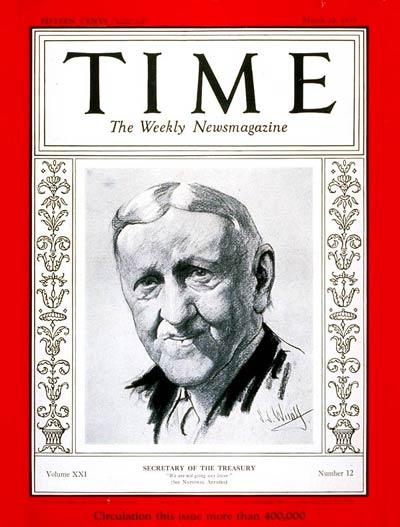

The next day, Congress convened at noon. Representative Steagall entered the House waving the only copy of the bill, which passed the House on a voice vote after 40 minutes of debate. Some members of Congress never got a copy to read. The Senate also passed it quickly, and it was signed on the fourth day of Roosevelt’s presidency. For Woodin, it was a triumph, putting him that month on the cover of Time magazine.

On Friday, March 10, Woodin personally supervised the Treasury printing of $2 billion in new greenbacks (equivalent to $47 billion in 2023 dollars). To save time, he used leftover, partly printed 1928 series notes. He organized a superb publicity campaign. He brilliantly had himself filmed standing by the presses and holding up stacks of uncut notes, and then waving off armored trucks heading from the Treasury to the banks. Pathé News and Universal Newsreel showed clips in cinemas everywhere. Word got out — cash was on the way!

On Sunday, March 12, Woodin met four times with Roosevelt as the president finalized his first radio fireside chat, which reassured the public that bank deposits were safe. The next day, the crisis was over. It had all worked. Marvelously, the lines of depositors clamoring for withdrawals disappeared. Depositors even patriotically returned gold they had withdrawn.

Will Woodin was at the heart of the creation and passage of the emergency legislation. Raymond Moley said: “If ever there was a moment when things hung in the balance, it was on March 5, 1933. Capitalism was saved in eight days, and no other single factor in its salvation was half so important as the imagination and sturdiness and common sense of Will Woodin.”

Meanwhile, the messy triage proceeded. After reopening the solvent banks, 4,000 banks remained shut. Some of them reopened later with help, the rest were out of luck. In the process, Woodin made some major friends for Roosevelt. California bank regulators wanted to use the crisis as cover for closing A.P. Giannini’s upstart Bank of America, whose 400 branches primarily served Italian immigrants and competed with bigger banks. Woodin told California officials that if they closed the bank, it would be their responsibility. Those officials backed off and the bank reopened. Woodin’s empathy for ordinary working people drove his intervention. A grateful Giannini switched his allegiance from the G.O.P. to Roosevelt.

It would be three more months before the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act was passed, formalizing Woodin’s emergency law and deposit insurance, which was strongly supported by smaller banks and the public. Senator Glass sought more stringent regulation of banks and Wall Street. Woodin, although initially skeptical of deposit insurance, worked with Treasury staff to improve the bill and worked on Roosevelt and Senator Glass to accept deposit insurance as a trade for more financial regulation.

The 1933 Glass-Steagall law gave America the F.D.I.C. and the framework for the Securities and Exchange Commission. It also gave the country a half-century of financial stability. It was the most enduring legislation of the famed first 100 days of the Roosevelt era. Deposit insurance has been praised by both left and right. Ending the panic created confidence in Roosevelt’s ability to govern.

East Hampton residents can be proud of Woodin’s legacy.

John Tepper Marlin, Ph.D., has served as a staff economist at two bank regulatory agencies and for Congress’s Joint Economic Committee. A Springs resident, he is writing a biography of William H. Woodin.