Alexander Svarre, a 17-year-old rising senior at Manhattan’s Dwight School, has been spending his last summer before graduation as an intern for the East Hampton Village mayor’s office, working on a very specific task: documenting the memorial plaques under 492 trees located throughout the village.

“This is the interactive map I created,” he said on Friday in the courtyard of the East Hampton Library, holding up his phone. The Google Maps app was open, zoomed in to frame the village. Small round tree icons were dispersed throughout the streets, most of them concentrated along Main Street and Newtown Lane.

The vast majority of the plaques were installed by the Ladies' Village Improvement Society, he said, and though they kept detailed records of the names and locations of all of their plaques, the records did not include any additional biographical information about the people memorialized.

"The mayor said that a lot of family members of these deceased people had come to him trying to find the plaques," Alexander said, and he learned that the mayor was looking to catalog and organize all of the information to make it more readily accessible. He suggested using Google Maps to create an interactive map that "anyone could just click – especially family members that don't know where their loved ones are."

The teenager has already plotted nearly 170 trees. Each listing, he explained, will contain a photo of the plaque beneath, and, ideally, a biography of everyone named. "Sometimes I can find them in the digitized archives of the East Hampton Star online, but whenever I can't, I jot down their name and then come here [to the library], and then I find the day that their obituary was posted in the Star, and they have it on microfilm."

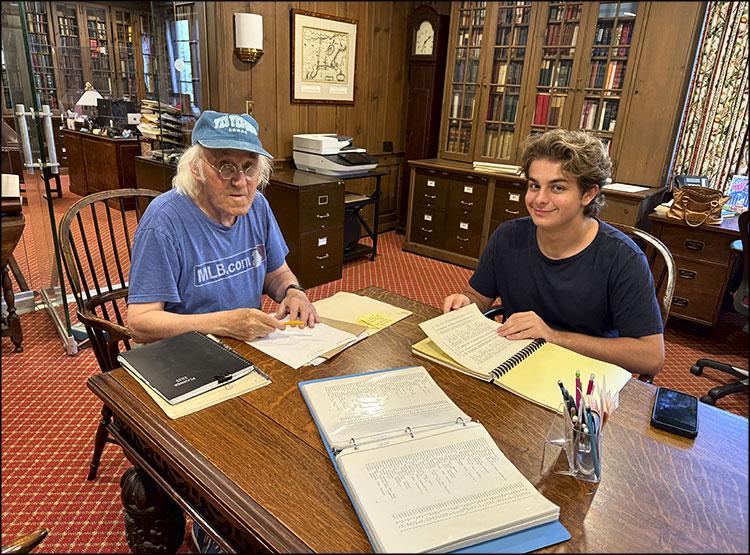

It was Hugh King, the town historian, who introduced Alexander to the library's microfilm archive, which has been "incredibly helpful" he said, in finding information about people he couldn't find online. He feels like he has the project "under control," but would welcome any additional biographical information about those honored on the plaques – particularly the ones that have no names attached, such as "Memorial Tree," or "Consider Removal," or "G.R.," for example.

It has been a lot of work, but he has always been interested in historic preservation, he said, inspired especially by spending summers and holidays in Wainscott — "one of the oldest regions of the United States" — from an early age.

"There's a lot of potential in the way that new technologies can be combined with these historical sites," he said. "A lot of preservation efforts don't take into consideration that times have changed. I get that the whole point of preserving something is for it to stay the same, but you still have to adapt."

He will continue to work on the map throughout the year. The plan is for it to available eventually on the East Hampton Village website. "I think history is sometimes taken for granted, and I feel like I always found it sad that some of these stories are lost to time," he said. "Each one of those is someone's life."

—

Correction: The original story, published online and in print, included a quote that incorrectly suggested the Ladies Village Improvement Society had not kept track of plaques it had installed by the trees. Alexander Svarre clarified in an email after publication that the L.V.I.S. had in fact kept a detailed and "very meticulous" list, containing the names and locations of the trees and their plaques, which he is using as the foundation for his research. His comment referred to the fact that the records did not track additional biographical information about the individuals memorialized by the trees. That is the main focus of his efforts, and is intended to augment the existing records and will ultimately appear alongside the L.V.I.S. data on the interactive map, so as to make all of the information more easily accessible to the public.