Isolation, anxiety, and uncertainty over the future has resulted in a declaration of a national state of emergency in child mental health by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. It is a fraught narrative repeated by pediatric psychiatrists across the country against the backdrop of a drawn-out pandemic.

On Tuesday evening, as a response to this growing concern about the lasting impact of the pandemic on children's well-being, a free trauma-informed coaching session was offered by I-Tri, the East Hampton organization whose goal is to empower middle school girls through fitness, and the Center for Healing and Justice Through Sport, a national organization offering solutions and resources for coaches and sports programs for children experiencing trauma.

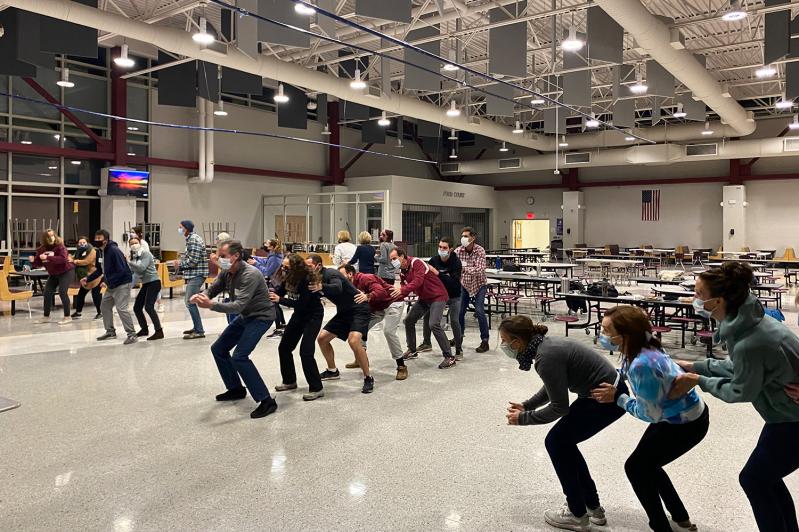

About 25 athletic directors, coaches, administrators, and community members gathered in the cafeteria of East Hampton High School for a participatory workshop led by Jillian Green Loughran, a lead trainer with the Center for Healing and Justice. The group was coached through a series of activities aimed at building confidence, connections, and simply having fun.

"It provides movement," Ms. Green Loughran told the group, of the activities in which the group participated. "And that's the goal of a lot of our sports programs we're doing with our young people, especially now. They've been in front of computers for a year and a half. They have to get back to movement."

Many of the techniques employed by C.H.J.S. are backed by neuroscience research that shows the physiological and psychological healing effect on children who participate in sports.

Dr. Bruce Perry, whose groundbreaking book (with Oprah Winfrey), "What Happened to You? Conversations on Trauma, Resilience, and Healing," which was published in April, provides much of the science behind the model of trauma-informed coaching offered on Tuesday.

"Sport is naturally structured to provide relational dosing that is much more therapeutically sensitive than traditional therapy," Dr. Perry is quoted as saying on the C.H.J.S. website. "If we make coaches 5 percent more trauma-informed, or developmentally sensitive, we will have more therapeutic impact on children than if we trained an entire new cohort of trauma therapists." He is also a senior fellow of the Child Trauma Academy in Houston.

"There's a myth that children are resilient," Dr. Perry said. "If anything, we now know that children are more vulnerable to trauma than adults."

Tuesday's participants were led through a series of exercises, such as fast feet, playing air tennis with a partner, and shuffling from side to side. These repetitive actions, or Patterned Repetitive Rhythmic Activity, said Ms. Green Loughran, have been shown to mimic the sound of a mother's heartbeat in utero, and can often act as an antidote to stress.

Another strategy discussed was the importance of personal greetings and goodbyes at the beginning and end of sports sessions. The use of first names, high-fives, and engaging in light conversations with a quick check-in enables coaches to build connections and trust with their athletes, and provides an all-important opportunity to talk.

Ms. Green Loughran also pointed out that a simple strategy such as starting and finishing coaching sessions with students in a circle, has been proven to have a calming effect on children who might be experiencing trauma.

"Circles are inherently safe," she explained, "because everyone can see each other. No one can creep up on someone from behind, without somebody in the circle seeing them. Everyone has everyone's back," she said. By ending a session in a circle, children feel more secure as they return to a stressful world, and the knowledge that tomorrow they'll be back again in this safe circle offers security and positive reinforcement that's key to helping children recover from trauma, she said.

The aftermath of a long quarantine and a severely altered lifestyle has virtually obliterated support systems and coping mechanisms for children of all ages. Psychologists point out that those who have additionally experienced childhood and adolescent trauma are particularly vulnerable right now.

According to Dr. Perry's research, in a normal brain, the stress-response mechanism, perfected through evolution, will switch on and off, priming the mind and body for danger. It then returns the nervous system to an equilibrium once danger has passed. But in extreme or prolonged trauma, reminders of the incident can keep flipping the switch on, overstimulating stress hormones, causing the heart to race and the mind to focus solely on survival. With a generation of young people experiencing this heightened state of stress on a daily basis, creative thinking is urgently needed to prevent a generation of children being scarred for life, mental health experts have warned.

Craig Brierley, East Hampton's swimming coach for high school boys and girls, who attended Tuesday's session, said he found the workshop very helpful. He also said that many of the techniques discussed were ones he already employs, adding that he was a big proponent of Dr. Perry's theories.

"As soon as kids jump into water, their bodies go into a state of stress," he said. "So, I work with kids to keep them comfortable in the pool. And I do that through connections and love." He admitted that maintaining these important connections through Covid, with social distancing and face masks, has been challenging. "But, as I always say to my athletes, "You win or you learn," he said.

Ms. Green Loughran also emphasized the need for administrators to coach parents, because children so often mimic their parents' responses to stress.

"I see it all the time," said Bridget Ehmann, a volleyball coach at the Southampton Middle School. "Parents regularly say, 'I don't know what to do with him,' and he's sitting right next to them! So, this was very helpful because we have to change the language."

Jessica Sanna, a phys. ed. teacher at the John M. Marshall Elementary School in East Hampton, echoed the underlying challenges facing teachers today. "We have a lot of kids who are still coming into school and we don't know always where they're coming from. Some are coming from very stressful situations. So, I think this was good because it gave us some tools and resources to get to know the kid and make them feel comfortable to deal with other people and new situations. And it gave us the tools to let them know that it's okay to feel sad, and scared, and angry."