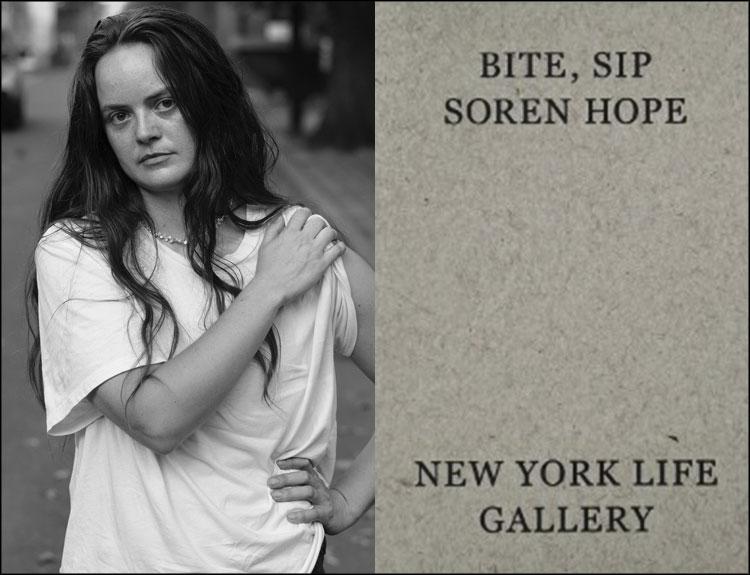

“Bite, Sip”

Soren Hope

New York Life Gallery, $35

Circa 1860, Pierre-Hubert Desvignes, an engineer, architect, and artist, invented what he called the folioscope. In 1868, John Barnes Linnett, a lithograph printer, came up with a patent for the kineograph. These are the 19th-century foundations for the flip book, a.k.a. the flicker book. It’s an early form of animation in which a series of images stacked in sequence gradually change to create the optical illusion of movement when the pages are thumbed. In the early 20th century, the Cracker Jack company popularized flip books by putting them in their product boxes as prizes.

Various artists have experimented with the flip book form — online, examples from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Thomas J. Watson Library show a fruitful range of works. And now, the artist Soren Hope chimes in, hermit-crabbing the flip book format with a certain exploratory, emergent, airborne feel, a gesture toward the capture of flux itself.

Flip books are much more humble than high-brow, yet the touch of nostalgia, even the adjacent whisper of kitsch, is a kind of currency. Published by New York Life Gallery on the occasion of its exhibition “Soren Hope: Two Time” (the artist’s first solo show in New York City, on view at the Canal Street space through Nov. 1), the book lands at a juxtaposing juncture: It’s a sophisticated limited-edition art book printed in a format for Cracker Jack eaters.

“Bite, Sip,” the light-touch title of the work, suggests both a sequence of action and a context, the bodily activity of intake, consumption, partaking. In the series of black line drawings on white fields, initially thicker, dense, dark marks give way to lighter lines, splotches, dots, irregular rings, unclosed loops, mote-like particles. Loosely represented figures with hands and mouths move and shift. Hands come to mouths. There are noses, expressions, definitely some eyes. Faces are legible, then less legible, then illegible yet still understood as faces. Marks spill over the field of the page, regroup.

Maybe this is what happens when ideas make their way inside? There’s a sense of absorption, reconstitution. The images in the book do not tell a story or present a concrete progression, but describe a flow of density and diffusion, clustering and dispersing, gathering, scattering. Bringing it in, giving it up.

Clear, utilitarian book design by the writer/designer/creator Claire Hungerford has materialized an object of some heft, sturdy and ready for action, bound rewardingly. The action of flipping the book is satisfying, like opening and shutting a certain type of clasp.

A hard-working, economical but not skimpy essay on Hope’s practice by Jennifer Pranolo accompanies the book, unconventionally placed in the middle of the volume. And so, it is demonstrably not an introduction, foreword, or preface. This resituating of accompanying text acts as an interruption to common consumption patterns, yet does not interrupt the actual experience of the book because it is printed on the other side of the pages the flipper is flipping. The essay does not usurp the privilege of orienting the viewer nor does it angle in on the action. Titled “Un-Finitudes” (an inverted plural!), the essay mingles sense of mission with fine discretion. It does not presume. A well-wrought addition.

This is a real and actual flip book; e.g., it doesn’t work if you thumb it back to front, or upside down. No, you flip it beginning to end. This gives way to the experience. Contradictorily, there are some drawings, appearing in sets, placed on the “wrong” side of the page, which make their own sequence, perhaps in reverse. A hand? A can? Or a shaker shaking out elemental bits, but also becoming elemental bits. Maybe a footnote. Or maybe an allowance, an indulgence for the uncontained, and that which develops from it. Perhaps Hope simply suggests that we consider the flip side.

If there is deconstruction of the flip book afoot, it comes with a handy, dual approach: The images are abstracted, in turn abstracting the flip book form, lofting the question of the flipper’s experience: What is it to come together and what is it to come apart? There’s a frankness here in spite of the elliptical quality of the progression. Nothing is hidden, interpret what you see, airiness coupled with solidity. The flip book requires its viewer to activate its technology. It’s an intimate experience between the flipper and the object being flipped.

And so, the viewer is implicated. Whatever mysterious bunching and diffusion of experience is happening here, you are making it happen, and it is happening to you — conjoining, coming apart, and apart in other directions as movement itself creates new space for further becomings.

Soren Hope, who grew up on the South Fork and attended the Hayground School in Bridgehampton, lives in New Haven, Conn.

Evan Harris is a writer and librarian living in East Hampton.