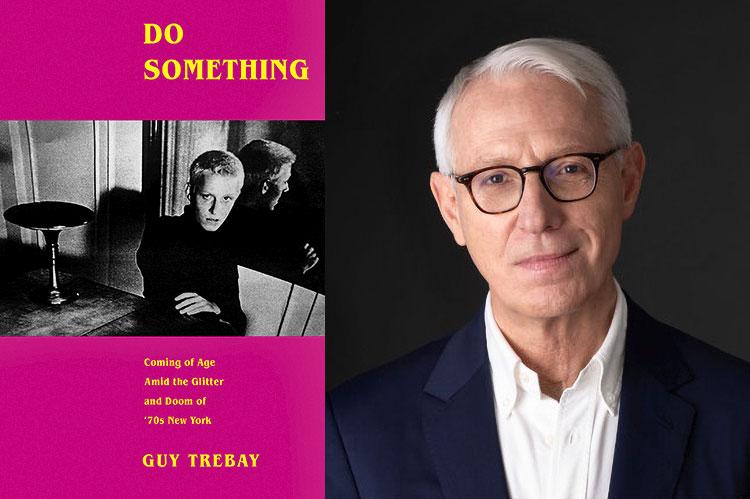

“Do Something”

Guy Trebay

Knopf, $29

Writing the story of one’s own life and time, in a manner that captures and holds the attention of others, requires considerable skill. In light of a surfeit of mediocre memoirs over the last few decades, a high-quality exemplar of the genre is immediately recognizable. And makes for a most satisfying read.

Guy Trebay’s new book, “Do Something: Coming of Age Amid the Glitter and Doom of ’70s New York,” is a small masterpiece — of writing and of thinking.

Mr. Trebay’s byline will be widely familiar, as he has for many years written on style, culture, fashion, and art for The New York Times. Readers of a certain age will also recognize his name as a writer for The Village Voice during its heyday in the 1970s and early ’80s — in other words, during the same period he writes about here.

The family into which Mr. Trebay was born, in 1952, lived on the Gold Coast of Nassau County’s North Shore (think “The Great Gatsby”). They found themselves in greatly reduced circumstances — except for the period during which his father made and lost a fortune manufacturing a men’s cologne popular at the time. (“We were interlopers, yes, although not quite imposters. My parents were nicely brought-up people, yet too uncynical and guileless to apply themselves to the hard work of social climbing. Maybe ‘impersonators’ is the word. . . .”)

As a family, the Trebays were broken, though not dysfunctional. They could not depend on one another, and each seemed to go their own way. The rogue of a father was essentially absent. The mother was scattered and distracted. One sister disappeared for a decade, during which she was on the lam, having committed armed robbery (for which she was eventually arrested and served time in prison).

As a result, young Guy, by his late teens, was rudderless and without any sense of what to do with his life. All he knew for certain was that he was not headed for college. (“As for me, any expectation that I would pursue higher education dwindled so steadily that I barely stumbled through high school. . . .”) He could easily be described as lost — experimenting with LSD, staying with a succession of friends on decrepit couches in vermin-infested apartments in a number of New York City’s most rundown neighborhoods. The word “shoplift” appears no fewer than seven times.

Unlike many other “lost” young people of the period, Mr. Trebay was at least motivated to find work, beginning with the utterly menial, in order to (barely) support himself. Along the way, he poured juice for patrons at a disco, modeled for men’s fashion illustrators, drove a school bus on Long Island, sold leather goods in a “hippie cobbler shop” in Greenwich Village, and worked as a night-shift busboy at the “in” nightclub and restaurant Max’s Kansas City. It was at Max’s, frequented by Andy Warhol and his circle, that Mr. Trebay got to know some of the Factory regulars, such as Jackie Curtis and Candy Darling.

A clerical job at The Village Voice introduced him to a colorful cast of bright, idiosyncratic writers who battled each other frequently, both in the pages of the weekly paper and in the office. In the minor writing he was finally allowed to do, we see the seeds of what became a long career that remains active today.

To observe that this book is in a minor key is in no way to denigrate it; some of the most sublime music ever written, after all, is in a minor key. It is to say, however, that happiness and excitement almost never appear. What is pervasive is uncertainty, worry, and fair measures of struggle and regret. The overarching joylessness that pervades the New York of this memoir is perhaps best represented by the elegiac allusions to the scores of Mr. Trebay’s friends who fell victim to the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s.

It is worth noting the extent to which the author’s personal story mirrors the decade in New York on which he primarily focuses. Like his family, the city is badly broken. The end of prosperity has led to disintegration. That very disintegration, however, gives rise to a burgeoning anti-establishment outpouring in music, art, and other creative fields. (“On the magical stage set of a broken-down city, these people — my friends, my dramatis personae — costumed themselves in an array of improvised and constantly mutating identities, revising them as needed, shedding them at whim.”)

Similarly, the lack of order in his life enabled Mr. Trebay to proceed step by step, day by day, along a circuitous path to finding purpose in his own life. Speaking in general, he writes, “Looking back, I see that there is something about the broke and crippled city that makes it hospitable to talent, something beyond the obvious explanation that rents are cheap. . . . Passion is a currency. So is the raw talent that, for now, seems enough to get a foot in most doors.”

Speaking about himself, he adds elsewhere: “Fortune is, as usual, the dominant force. How else to make sense of the way that years spent hanging around creative oddballs, drugged-up drag queens with washed-up Hollywood characters and the Warhol-adjacent, will turn out to have been enough education to enter any kind of profession, let alone one I have never for one second considered pursuing?”

A prominent feature of “Do Something” is that it comprises a single (long) chapter. There is no interruption between the dedication page at the beginning and the acknowledgments, 243 pages later. This creates the impression that it was written in a single burst, as one long memory. Although such cannot be the actual case. It puts one in mind of Proust, in whose work an explosion of memory serves to unearth an entire world and leads to the inevitable creation of art.

Satisfyingly, the author’s personal family story has a good ending. At the very beginning of the book, he describes his searching for a box of family photos in the burned-out shell of his family’s home, following a devastating midwinter fire. The symbolism is impossible to misinterpret. Much later, however, he writes, “Yet, for all my parents’ apparent carelessness, there was a core of love, and I am grateful to them. . . .”

In two other ways, moreover, Mr. Trebay alludes to the eventual repair of his family relationships. One is that this memoir is dedicated “To my siblings.” The other is that the enigmatic title he chose echoes his mother, at the exact end of her life. Awakening from a coma, “suddenly she clutched my hand with tremendous primal strength and spoke her last words: ‘Do something.’ “

Indeed, her son has done something quite marvelous.

Jim Lader, who owned a weekend home in East Hampton for many years, has reviewed books for The Star since 2009.