“Long Island State Parks”

Kristen Matejka

History Press, $24.99

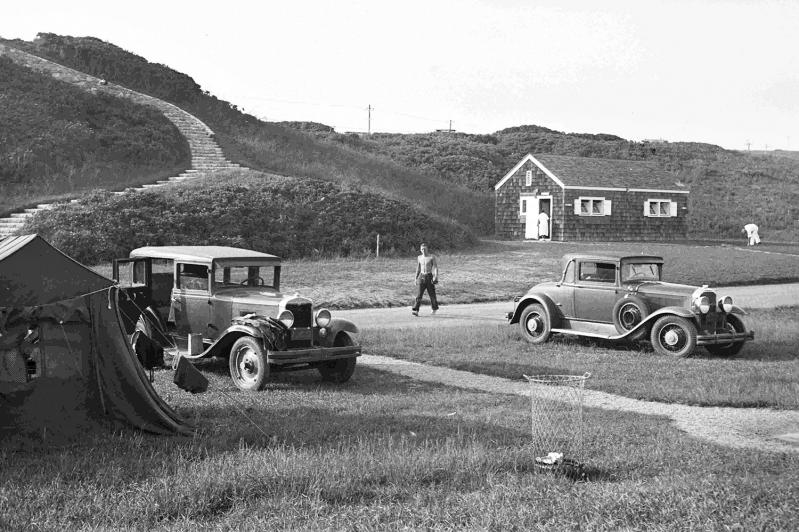

I doubt I’m alone in saying my first experience with a state park on Long Island involved car camping at Montauk’s Hither Hills. It may be mostly a parking lot, but what a parking lot. The roar of the ocean. The evening’s twinkling lights. The proximity to the camper with the guy in the wife beater, beer can in one hand, middle finger ready in the other, issuing orders from his lawn chair to his long-suffering spouse, memorably dubbed “You dumb [rhymes with witch].”

But times have changed. And while a social history of New York’s parks would be most welcome (the maulings at Bear Mountain brought on by inappropriate feeding, and so forth), what Kristen Matejka has given us in her new “Long Island State Parks” is straightforward background, almost a guidebook to lands that, in all sincerity, we’re lucky are there at all.

First we must address the colossus in the room, Robert Moses, king of the urban planners, whose innumerable titles included chairman of the Long Island State Park Commission, which at its outset in 1924 looked upon a very different place — “sparsely developed, there were no major highways, and most of the island comprised rural farmland with unpaved roads,” Ms. Matejka writes. Six years later, sufficient acreage had been acquired “for thirteen major parks and the land to construct major portions of the parkways leading to them.” Today, there are 27 such parks on Long Island.

And you can’t have Moses without his biographer, Robert Caro, East Hamptoner, and his epic “The Power Broker,” which Knopf rereleased this week as an e-book for its 50th anniversary. These days Moses may be primarily known as a destroyer of New York City neighborhoods, but here Ms. Matejka quotes Mr. Caro to highlight another legacy: “As for the parks he created, fly over New York in the year 1999, and the two thousand acres of Brookhaven Park and four thousand acres of Connetquot on Long Island, and the twenty-one thousand other acres of parks that Robert Moses wrested away from the developer’s bulldozer to insure that the people of New York would always have green space that will still be green is a tribute to his foresight.”

As for hindsight, let’s face it, the Montauk park history has been done. Sunken Meadow State Park in Kings Park, now that’s a different story, and always a relevant one, given the legions of high school cross-country runners and their parents who visit it every year for meets traversing one of the most difficult courses in the country.

Taking its name “from a vast, sundrenched meadow that once extended from the calm waters of the Long Island Sound to the high, forested bluffs behind the park,” Sunken Meadow was cobbled together over the years from the estates of several landowners, including one Caroline Platt, a descendant of Zephaniah Platt, who during the Revolutionary-era British occupation of Long Island aided a spy network in getting information about British troops to patriots across the Sound in Connecticut, then on to General Washington. The Platt house still stands nearby.

“In 1992, Sunken Meadow was renamed Governor Alfred E. Smith Sunken Meadow State Park,” Ms. Matejka says of the man who served in that capacity for almost all of the 1920s. “While Robert Moses receives much of the recognition and credit for creating the state parks and parkways on Long Island, Governor Smith was the one who gave him the ability to do so. Smith, known for his progressive agenda in education, workplace rights, housing, and welfare, was an adamant supporter of creating parks for the public’s use and enjoyment.”

In that way taking a cue from the ultimate Long Islander, Teddy Roosevelt. And as with the string of state parks up and down the Oregon coast, the timing was auspicious. Such public-mindedness is long since dead and buried.

Kristen Matejka serves on the Town of Smithtown Historical Advisory Board and on the board of the Kings Park Heritage Museum.