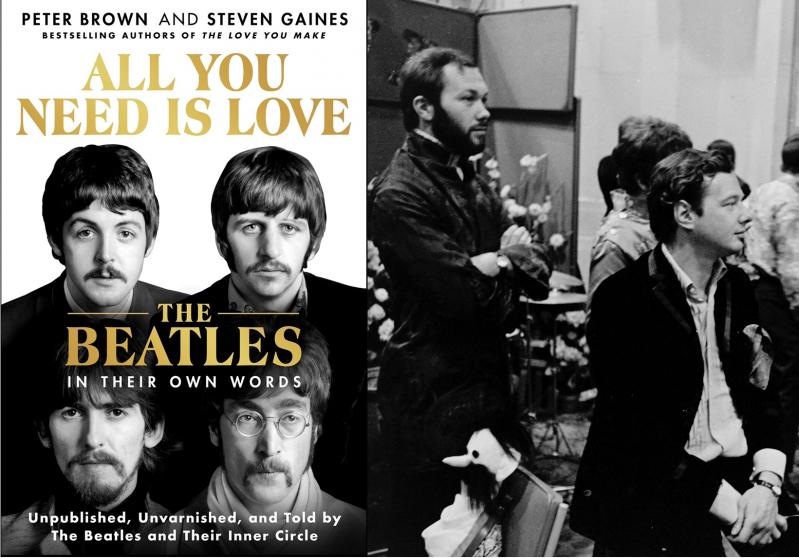

“All You Need Is Love”

Peter Brown and Steven Gaines

St. Martin’s, $32

About 25 years ago I was in a rehearsal studio on the West Side of Manhattan, a multilevel music facility that always had a lot of bustling rock-and-roll activity. In addition to its many rehearsal rooms, notable national acts stored their gear there, so you’d always see panicked roadies racing against the clock loading them in and out, shouting to each other up the stairs, amps in each hand, sweating cardiac buckets of last night’s hangover into their bandanas — all looking like Rambo in the last frame of “First Blood.”

There were also a couple of plush showcase rooms on the first floor that big names like David Bowie or David Byrne would block out for a week or two to get their bands ready for a tour. It was commonplace to walk into the front desk lounge and hear someone like Patti Smith belting one out in the big room down the hall.

One day I heard this odd-sounding two-part vocal, a high-pitched woman’s voice blending with a male singer over some noise rock. I got excited and thought it was Sonic Youth or maybe Yo La Tengo, so I asked the gruff guy at the desk if it was either of those acts, and he said, “Nope, it’s Yoko and Sean. They’re gonna be here all week. The boss instructed us to tell everyone not to go up and try to talk to them or say anything stupid, so let all your guys know. Got it?”

I said, “Yeah, of course.”

A couple of days went by, not ever seeing them, and I had to go into the office to inform the powers that be that the soda machine wasn’t taking dollar bills, and who do I see in front of me at the desk getting quarters but Yoko. I was a bit startled but I remembered the protocol and waited quietly, eyes down, maintaining the poker face of a pedestrian task, concealing the fact that change for a dollar had never been so thrilling.

The office always had a few of the sound techs in there with the manager, Jim, holding court. You would occasionally hear them wheezing up riotous road stories, smatters of small chuckles that would intermittently crescendo to an uproarious group laugh. Sometimes when you walked in, a sudden hush would fall upon the room, and you’d feel that thing of not wanting to be a lingering killjoy.

The boys were all in there on this occasion as Jim handed Yoko the quarters. She uttered a pleasantly meek “Thank you” and made for the door — a routine exchange by any standard until she got a few feet away, when, under his breath and to his cronies only for comic effect, he replied, “No, thank you . . . for breaking up the Beatles,” and right at the incline of their stealthy snickers she stopped short, her back still to them.

Sheer terror had now entered the room. Had she heard it? Time stood still and within it an agonizing silence. She started clinking the quarters back and forth from one hand to another intensely, like Captain Queeg and those two steel balls in “The Caine Mutiny.” It felt like it could be a tick-down to her wheeling around and exploding on them. She continued the repetition of that for what seemed like an eternity but was probably only about a minute or so, and then casually strolled on, never turning around.

There was no need for a showdown. She had employed psychological warfare and handily won . . . or she hadn’t heard the comment at all and was just counting the quarters and doing math in her head for the soda machine. I guess we’ll never know. We heard the quarters go into the machine, the cans come tumbling out, and she made a swift exit. The synchronized sigh of relief we let out was almost enough to blow back the blinds.

On my way back up the stairs to our rehearsal room I wondered how many times through the years Yoko had been forced to navigate something like that. Admittedly, it was a brief contemplation followed by my charging up the rest of the steps and half out of breath blurting the whole suspenseful sequence to my bandmates and a few of our musician friends from neighboring rooms.

After my campfire captivation of the second-floor common space, we all started to kick around the age-old question, did Yoko Ono break up the Beatles? Our consensus was no, that she was merely the most cited symptom of the band’s ending, but what the hell did we know? We didn’t know any of the people involved or how things really transpired, so our conversation could never be anything more than fan conjecture.

In Peter Brown and Steven Gaines’s highly illuminating new book, “All You Need Is Love: The Beatles in Their Own Words,” you actually get to meet the ones who do know and get their take on whether Yoko’s presence sped up the corrosion of the group, or did the death of their beloved, yet troubled, manager, Brian Epstein, set them adrift irreversibly? These and many other nagging questions and pervading theories regarding the Fab Four story are addressed.

It’s all done by way of an oral history with inner-circle friends, ex-wives and girlfriends, former employees, misbegotten gurus, important influencers of their careers, and the Beatles themselves. There are fascinating interviews with names you’ve only heard referenced in Beatle lore, like Alexis (Magic Alex) Mardas, John Lennon’s ex-wife, Cynthia Lennon, Patty Boyd Harrison Clapton (the muse, she speaks!), swindling business manager Allen Klein, legendary press agent Derek Taylor, and their no-nonsense rock-sturdy road manager, Neil Aspinall (my favorite interview in the book), among many others.

The result is an unparalleled dish on the inner workings of the mop top magic machine and a fun peek behind the curtain of swinging ’60s London.

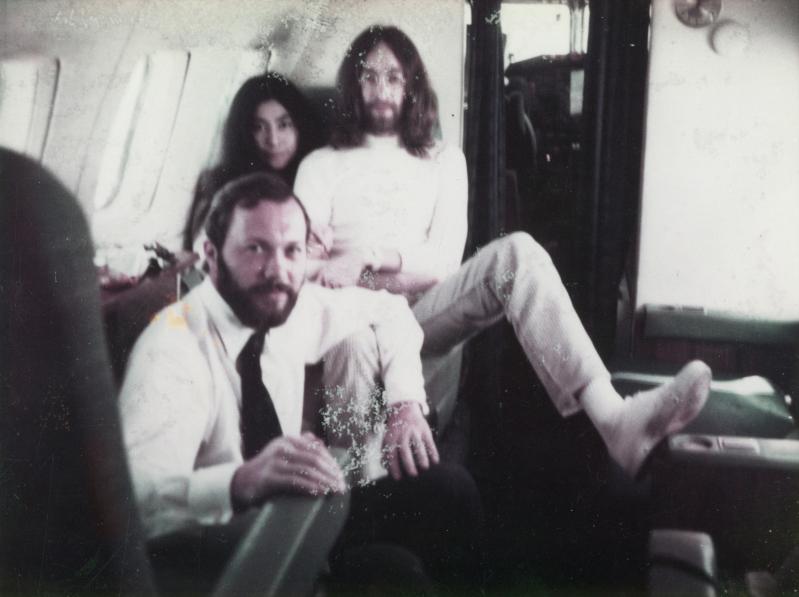

Perspective is everything. What’s most compelling about this collection of interviews is that, with the exception of Yoko’s, they were all conducted in November of 1980, only weeks before John Lennon’s assassination — one of the saddest days of the entire decade and beyond. It was all done for a book that was to be published the following year and never reached the shelves, for obvious reasons.

The band had ended only nine years prior, so all of the subjects’ resentments are still pretty fresh, their accounts of things crystal clear, and because, in most cases, it no longer would affect their jobs or their relationships within the group, they give unflinchingly unfiltered answers.

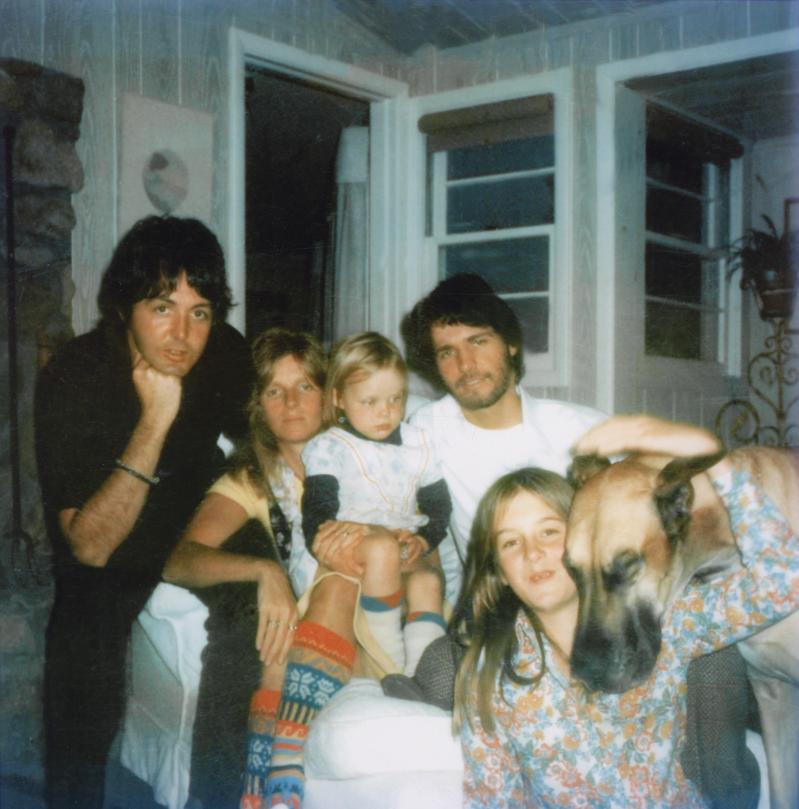

George Harrison and Paul McCartney are overtly angry with John Lennon in their interviews and don’t pull any punches about it at all. In fact, when Mr. Gaines informs George he’ll be interviewing Lennon when he returns to New York, Harrison curtly replies, “You’ll probably think John is a piece of shit. He’s so negative about everything.” Moments like that serve as an eerie time capsule, knowing the dark month of December that approaches and how that interview will never take place.

The line of questioning always lifts out to a more casual and off-the-cuff conversation. The reason for this is they’re talking to someone they know well in Mr. Brown, the former C.O.O. of Apple Corps and a trusted friend/employee hired by Brian Epstein who had been with the Beatles from their early days in Liverpool, through Beatlemania, and in the fire with them every step of the way till the end.

Epstein famously saw the Beatles at the Cavern Club and thought they “had something.” That something turned out to be more than just enduring but eternal. His story is deeply discussed in this book, and it’s tragic but beautiful in the relationship he had with the four lads and their love for one another through uncharted waters of constant chaos.

The image of the suited-up mop tops doing their group bow on “The Ed Sullivan Show” is emblazoned in our brains. This book gives Brian his bow.

Christopher John Campion, a singer-songwriter and regular visitor to Amagansett, is the author of “Escape From Bellevue: A Dive Bar Odyssey,” published by Penguin-Gotham.

Steven Gaines lives in Wainscott, and Paul McCartney lives part time in Amagansett.