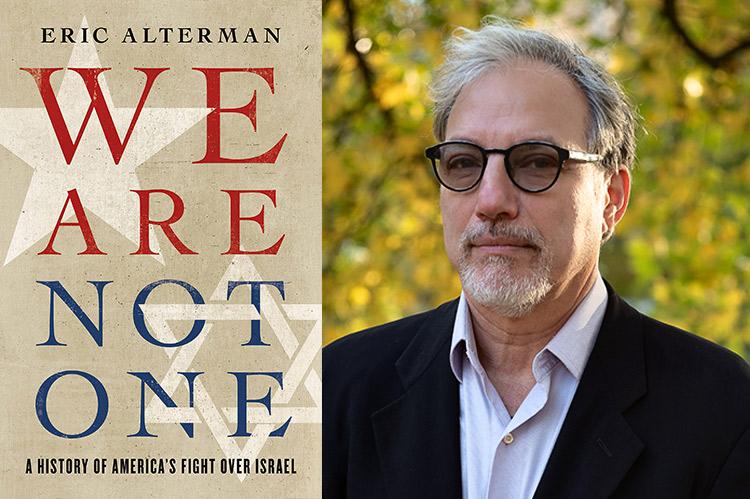

“We Are Not One”

Eric Alterman

Basic Books, $35

Early in "We Are Not One," the proudly liberal political-social-media commentator Eric Alterman admits: "I don't doubt that this work will invite considerable criticism by those who see their own side treated in a manner they consider to be unsympathetic or lacking in the crucial fact or insight that would, in their eyes, undermine my entire analysis."

It may well be the one line least likely of all to be contested in this hefty, diligently detailed, footnoted, and indexed exploration of the long-running, continuing debate over Israel among Americans — often most angrily, even bitterly, among American Jews.

And the recounting takes on new resonance today with escalating Palestinian attacks and typically controversial, asymmetric Israeli counterstrikes (some violating international law, various human rights groups have concluded) under the restored leadership of the right-wing Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, along with worrisome changes to the nation's judiciary and accelerated expansion of "settler" homes in Arab territory.

Only weeks ago, we learned, the number of such settlers now exceeds 500,000 — arguably a tide not easily turned in the future (if it ever was) for some form of more peaceful co-existence. "We've reached a huge hallmark," a resident of the Beit El settlement on the West Bank told the AP. "We're here to stay."

Here to stay as well, according to polls Mr. Alterman cites, may be a more or less steady decline in approval of Israel — at least its Palestine policies — among all Americans, American Jews, and especially their younger generation. Of which more later.

Terms of the debate have shifted along with facts on the ground, with some tricky ironies here and there.

In 1948, President Harry Truman went maddeningly back and forth with his State Department, led by the World War II hero George C. Marshall, and warnings that to recognize a newly self-proclaimed state of Israel would threaten U.S. interests in Arab oil and Arab support to block Moscow's Cold War Mideast designs, possibly dragging U.S. forces in to prevent another Jewish massacre. Not to mention allegations that some socialist-minded European refugees might make a "Red Fifth Column for Palestine," as Mr. Alterman finds in The New York Times.

Also opposed, surprisingly, were some major American Jewish leaders who feared that an established Jewish state could lead to charges of "dual loyalty" against assimilation-minded American Jews — and thus aggravate antisemitism.

These days, many such leaders argue that it is criticism of Israel and its treatment of Palestinians — especially from outspoken American Jews — that promotes a rising tide of antisemitism at home and abroad. Not the harsh policy itself, despite the world's current, post-colonialist concerns for all subjugated, persecuted, and disadvantaged minorities.

Truman himself was aggravated by the endless pleas of dedicated Zionists for U.S. recognition of the new nation — albeit less so those brought personally to the Oval Office by First Friend Eddie Jacobson, his World War I Army buddy, later business partner (see: The East Hampton Star's Aug. 19, 2021, book review).

Truman also was genuinely moved by the plight of homeless European refugees as well as their Old Testament history — which, Mr. Alterman suggests, he may well have seen himself continuing — and by the political realism of his new, non-Jewish White House counsel, Clark Clifford.

In a memo written as the 1948 election approached, Clifford noted of the rank-and-file Jewish "bloc" that "Unless the Palestine matter is boldly and favorably handled there is bound to be some defection on their part" — key to critical Northeast and Midwest urban votes.

And so Truman agreed. Indeed, Mr. Alterman argues, given the variety of Jewish practice in America — from ultra-Orthodox to Modern Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, even just two or three days a year — support for Israel soon became the common hallmark of American Judaism generally.

That support and the funds that came with it, both private and from constant political pressure on Washington, was really the only aspect of American Judaism appreciated by Israel's increasingly influential religious establishment. It disdained American Jewish practice, raised hackles by refusing to accept marriages performed by many less Orthodox U.S. rabbis and pronouncing that all Jews should move to their new homeland. "Every religious Jew has violated precepts of Judaism and the Torah by remaining in the Diaspora," Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion opined.

As Israeli nation-building accelerated, distance allowed American Jews to imagine the new nation as an "idealized dream world," in the words of Jonathan Sarna, a Brandeis University historian — a dream eventually given flesh, Mr. Alterman maintains, by such as the Leon Uris novel "Exodus" and even more so by the movie idol Paul Newman starring in the film version.

Which made less likely the hope of the influential and otherwise insightful American philosopher Mordecai Kaplan that Jews in the U.S. and elsewhere would "likely . . . act as a brake on the chauvinistic tendencies that the Israeli struggle for survival is only too apt to arouse in the Jews of Israel." Especially after Israel's initial David-vs.-Goliath victory over the combined forces of its Arab neighbors, accompanied by the expulsion or fearful flight of 750,000 Arab civilians whom Israel "evinced zero interest" in permitting to return, Mr. Alterman writes, despite persistent pleas and pressure from the U.S. government, among many others. The "Nakba" (catastrophe), Arabs call it.

But as Mr. Alterman sees it, the guilt of many American Jews over not doing enough to save their co-religionists from Nazi obliteration, nor from shameful postwar survivor conditions, made it hard for them to intervene with "what appeared to be an unprecedented and heroic experiment in the reinvention of an ancient, battered people."

As Israel showed more military strength and daring — conspiring with Britain and France to invade Egypt's Sinai Peninsula in 1956, and most notably again in the Six-Day War of 1967 that "Israel's leaders decided to start [with Egypt and Syria] themselves," as Mr. Alterman reads the evidence — it also seemed more a useful ally.

And in the U.S. it began transforming shame and guilt into a new pride for many Jews, a kind of testosterone from afar. For others it was proof of God's justice.

"Herein lay the origins of one of the many absurd aspects of American Jewish discourse on Israel," Mr. Alterman writes. "The Jewish state was now a regional superpower and would soon boast the world's fourth most powerful" army with a military budget "greater than any four of its potential adversaries combined, to say nothing of its not-so-secret nuclear capability."

"And yet, because the discourse reflected emotion far more than rational calculation, the fear that the same nations would one day 'drive the Jews into the sea' rarely — if ever — receded. Indeed, it remained at the foundation of almost every public pronouncement by mainstream Jewish leaders in the United States and in the literature of virtually every fund-raising pitch."

But that contradiction apparently comes with a cost. By 2020, a Pew survey cited by Mr. Alterman found that fewer than half of American Jews under 30 described themselves as even "somewhat" emotionally attached to the Jewish state, and of those fully 87 percent agreed that one could be both "pro-Israel" and critical of Israeli policies. Across all ages, 58 percent of U.S. Jews favored restricting military aid to prevent its use in the occupied territories.

Whether or not this shift has any more practical effect on America's pro-Israel policy than previous critiques remains to be seen, especially in the new G.O.P.-controlled U.S. House of Representatives. Zionists were certainly pleased by the recent expulsion of the Somali-born Representative Ilhan Omar of Minnesota from the House Foreign Affairs Committee, ostensibly because of antisemitic comments for which she previously apologized.

But was her remark — "It's all about the Benjamins, baby" — really much more than slangy recognition of the massive pro-Israel political support that Mr. Alterman describes, orchestrated by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, or AIPAC, and other major Jewish organizations?

Ken Roth, the former Human Rights Watch head, blamed "donor-driven censorship" for Harvard's Kennedy School dean denying him a fellowship following a major Human Rights Watch report on aspects of "apartheid" in occupied Palestine. The dean denied it but recently reversed his decision after protests by the A.C.L.U. and hundreds of Harvard faculty and students.

And there is new American support for a tough Israel from neo-conservative activists and Christian evangelicals. The latter see Jewish rule over Palestine as the essential gateway to Armageddon and rapture for true followers of Jesus. "Unfortunately," Mr. Alterman notes, not for "all the world's remaining Jews." Muslims, too, he might have added.

Until then, however, it seems safe to assume that debate over Israel as detailed in this volume will go on — here, there, and most everywhere.

Eric Alterman has been a columnist for The Nation and The American Prospect. A professor of English and journalism at Brooklyn College, he has a summer home in East Hampton.

David M. Alpern, a former reporter, writer, and senior editor at Newsweek, also anchored the "Newsweek on Air" radio broadcast for more than 30 years, later the nonprofit "For Your Ears Only" show, and now hosts programs for local libraries in person or via Zoom from his house in Sag Harbor.