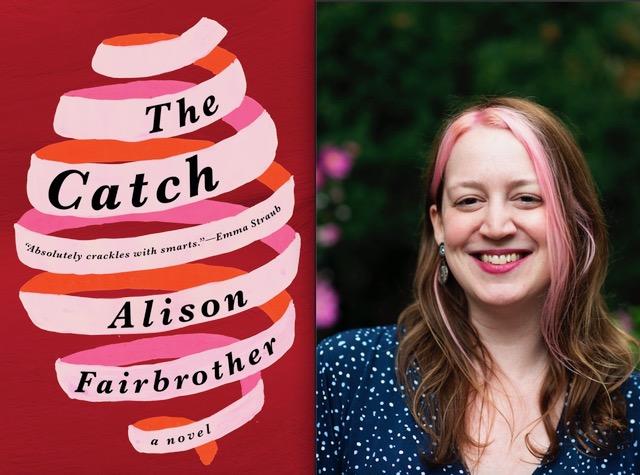

“The Catch”

Alison Fairbrother

Random House, $27

The one item my father left me in his will was a brass ashtray in the shape of Shea Stadium. It used to sit on the desk in his law office, the repository of his occasional cigar. Working for the nascent New York Metropolitan Baseball Club, he wrote the lease for the stadium the year I was born, so I had no choice but to become a fan. It was something we shared: playing catch, going to games — always to opening day, for which I swaggeringly played hooky from school. The ashtray, given to him by the Mets, was an uncomplicated bequest, as if my father had annealed his affection into its tarnished metal.

So I felt an immediate kinship with the narrator of Alison Fairbrother's sparkling debut novel, "The Catch." When her charismatic father dies of a heart attack, 24-year-old Ellie Adler assumes that he has willed her his lucky baseball, the one he kept by his desk as he wrote poetry, the one with which they played catch when she was young, a father-daughter communion that she assumes is the referent in his one famous poem, The Catch.

But James Adler throws his eldest daughter a posthumous curveball: He leaves her a joke tie rack in the shape of a gingerbread man, and the talismanic ball goes to an unknown person named L.M. Taylor.

The plot's engine is Ellie's search for this mysterious beneficiary, which leads her on a journey into her father's past, producing a book-length eulogy of a minor poet — though an odd paean that includes the deceased's peccadillos.

Yet this fast-paced, bracing novel is anything but mournful. It's set amidst the idealism of Obama-era Washington, D.C., where Ellie is starting her career as a journalist, living in a group house, dating an older married man who works at a think tank and can answer her questions about Sri Lanka.

Ellie's search for the person to whom her father bequeathed what she sees as her patrimony leaves an enthralling trail of destruction: to a marriage (involving a woman who turns out to have been her father's mistress); to the trusting nature of an osprey defender; to her own journalistic integrity; to the pedestal on which she put her father.

The question that haunts her seems to boil down to: If she was not beloved by her father, then is she lovable?

" 'I guess I wasn't his favorite after all — who gives their favorite a tie rack?' " Ellie laments to her lover, Lucas. " 'Why would he have led me to believe that I was his favorite? Like, what was he playing at? . . . But what kind of person is angry at their dead father?' "

In a recent interview, Ms. Fairbrother said that losing her own father in her early 20s caused her to think about how at that time of life you're "coming to terms with who you want to be in the world," but losing a parent "throws you back into the past. . . . Grief becomes a complicated laboratory of feelings."

Ellie looks for affirmation from Lucas, who is as unavailable as the father whom she shared with her three half-siblings, two ex-wives, and one current wife. As a psychoanalyst friend of mine says, "Freud wouldn't charge for this."

But this novel is built on layers of meaning, starting with the title. Catch as in: play with a ball; catch as in: an osprey catching a fish; but most of all, catch as in that word that douses excitement: But here's the catch. . . . Or, as Ellie reflects: "A divorced father put his children in competition with one another; the catch was that no one could ever win."

Though psychologically nuanced, "The Catch" is also firmly grounded in time and place. Ms. Fairbrother turns her anthropological eye on phenomena of the 21st-century American Millennial Tribe, including the mating rituals of internet dating — "I scrolled through dozens of men, as uncomplicated as skimming my hand over racks of silky underwear at a department store"; outposts of young activists and policy wonks like Ellie's housemates in D.C., observing as they play Monopoly: " 'The really preposterous thing about this game is that we all start with the same amount of money. When has that ever happened?' "; and journalism in the digital age.

Ellie works at a news site called Apogee (more of a nadir in her depiction). The Apogee office is, significantly, in a former snack cakes factory, where the reporters serving up their six tasty posts a day work beneath a Leaderboard that shows the top performers — which never includes Ellie, who covers the less sexy beats, like science.

As someone who started as a reporter at the venerable East Hampton Star on a manual typewriter, I was enlightened by the depiction of today's clickbait journalism, informed by Ms. Fairbrother's own work as a journalist in D.C.

The fitting backdrop of this book about a 20-something woman who feels she has been disinherited is the uncertain future of the planet. Ellie wakes up daily to an environmental-news bulletin for reporters:

"The earth had been diagnosed with end-stage cancer, and every morning I learned that diagnosis anew. At the end of this avalanche of disheartening statistics and thinly veiled recriminations, some volunteer administrator who had clearly been spending too much time with an adolescent granddaughter enclosed a GIF of a cartoon penguin leaping with joy. The penguin, meant to end things on a lighter note, was the worst part. 'Soon this will be the only penguin you'll ever see,' it seemed to say. 'Your grandkids will know only computerized penguins; and if in fact the planet still exists for your grandkids to process a computerized penguin, it is highly likely the planet will be so overcome that your grandkids will no longer know joy.' I dressed for work."

Ms. Fairbrother clothes her narrator's trenchant observations in humor so they become the sort of poisoned creampuff that might have been manufactured at the snack cake factory. She captures the looming apocalypse that millennials have to ignore in order to go on about their business in this one simple line: I dressed for work.

Although Ellie is a sharp observer of her surroundings, she has a blind spot when it comes to the interpretation of her father's most famous poem. The Catch (the poem) within "The Catch" (the novel) begins its free verse with a sentence fragment that has no beginning or end:

but,

if time could kneel, as a catcher

shifts to his knees when the pitch is wild

As she takes a breath before reading the poem at her father's funeral, Ellie reflects that "In The Catch, nothing came before but. The reader had to guess what the speaker had relayed before the poem began. The great absence at the beginning was the mystery."

The poem reflects her own fuzziness about her father's life before her, "the great absence at the beginning." She seems to know this poem so well, carries it in her purse even, and yet toward the novel's end, the beneficiary of the lucky baseball forces her to realize that she completely misinterpreted it, putting herself at its center.

The tonic note of the poem in "The Catch" is reminiscent of Vladimir Nabokov's novel "Pale Fire," which begins with a poem from which ensues a largely unrelated commentary by an academic relating the adventure story of his own life. A college professor of mine claimed that Nabokov wrote the whole novel as an excuse to publish the poem, which opens with a bizarre image of a bird killing itself by flying into a windowpane.

The Catch is similarly iffy as verse, and I wasn't sure if Ms. Fairbrother intended readers to take it seriously. But there's no question that her narrative voice percolates with poetry.

Here, for instance, is Ellie's stark depiction of mourners' attempts to reconstitute the dead at a funeral:

"I scooped food onto a plate and moved through a sea of people, floating. Their heads were enormous. They said, 'Your father bailed me out of jail — twice — when he didn't have any money to spare.' They said, 'Your dad saved me.' They said, 'You're a lucky girl to have had a father like Jim.' "

"Lucky, lucky, lucky girl. Beautiful speech. What a tragedy. Here's some cake. Here are some words."

The elusiveness of one comforting, definitive interpretation lies at the heart of this novel, as it does with James Adler's poem. "Dad always joked that getting royalties for poems was the equivalent of being paid for saying, 'Maybe,' " Ellie recounts. "Poetry was a way to be decisive about nothing, to ask endless questions, to be open to everything."

Likewise, Ellie's search yields troubling, ambiguous nonanswers and, in the end, a complex portrait of a father-daughter relationship for us lucky, lucky readers.

Ellie winds up with a much more nuanced sense both of who her father was and who she might become. What seemed to be the simple metaphor of a lucky baseball is now intricate: "I took my father's baseball from my purse and held it in my hand. Scuffed white, stitches faded to pink, a symbol of betrayal, of regret. Of love. A testament to the possibilities that existed between two people, the conversation that was passing a ball back and forth."

This narrator's odyssey is the sort where you round the bases only to return to home, but you're not the same person who set forth, and now the whole game has changed — for readers and baseball fans, a spectacle at once unsettling and thrilling to watch.

Alexandra Shelley, who lives part time in Sag Harbor, is an independent book editor and professor of fiction writing at the New School.

Alison Fairbrother studied in the M.F.A. program at Stony Brook Southampton. The late E.L. Doctorow of Sag Harbor was her grandfather.