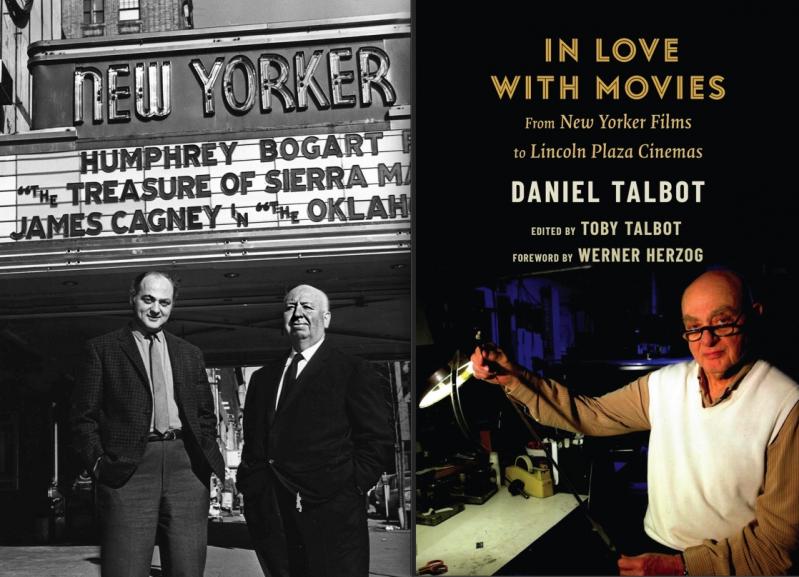

“In Love With Movies”

Daniel Talbot

Columbia University Press, $25

Broadly speaking, there are two kinds of people who go to the movies: The first, and much larger, group goes in search of entertainment and/or an escape from everyday life; the second, in search of art and/or intellectual stimulation. We call the latter cinephiles.

Daniel Talbot's recently published memoir, "In Love With Movies," reveals that he was equally comfortable, and equally well regarded, in both camps. Mr. Talbot, who died in 2017, was a New York City cinephile and movie buff who, for more than 50 years, played significant roles in movie theaters and movie distribution. His influence grew to be international in scope.

As a young man, Mr. Talbot left a publishing job for the luxury of spending a year "of quiet" during which he read widely. Returning to work, he followed his passion for the cinema. In March 1960, he opened the New Yorker Theater at Broadway and 89th Street on Manhattan's Upper West Side. ("Our first program was 'Henry V' and 'The Red Balloon.' A huge success. From that first day, the place had an electric atmosphere, virtually all of the customers young, with a genuine hunger for film — and not satisfied with the run-of-the-mill junk. All the shows ended with applause.")

Although it had not been his intention to become a film distributor, an encounter with the Italian film director and screenwriter Bernardo Bertolucci proved provident. ("From the outset, I resisted any impulse to distribute films. But it was the collector's high that kicked in when I first saw . . . Bertolucci's 'Before the Revolution.' I wrote to the Italian producer, saying that I wanted to launch it at the New Yorker Theater. He wrote back, 'No, I'm not interested in a single exhibition of the film, but if you want to buy the distribution rights, that's another matter.' ")

Thus was launched a significant aspect of Mr. Talbot's career. He founded New Yorker Films in 1965. The distribution firm became known for artistic, innovative, politically engaged films from around the world. It was this aspect of his work that impelled Mr. Talbot to attend a wide variety of international film festivals. (Excerpts from his notes from many of them form one of the valuable appendices of the book.)

At the Cannes Film Festival in 1991, Mr. Talbot was honored with the prestigious Rossellini Award. In his acceptance speech, he said, "If I have been working in cinema all these years, it is only because of Roberto Rossellini." He recounted how, as a young man, seeing two of the Italian director's films inspired him to pursue a life in the cinema world.

Mr. Talbot remained a film distributor for 49 years. During much of that time, he also owned and ran movie theaters. His last and largest was the Lincoln Plaza Cinema, which opened in 1981 on the lower level of a newly constructed apartment tower across from Lincoln Center.

This book is many things, and readers will find different aspects of it to be of the greatest value. It is virtually a reference volume on the most important art films of much of the 20th century, and on many of their creators. It is a sharply focused reflection of intellectual life on New York's Upper West Side during the same period. ("Rarely do I go below Fifty-Ninth Street or east of Central Park West.") It is a thoughtful consideration of the place of movies in our culture. Above all, however, it is a glimpse of one of the fortunate few — a man who turned his passion into a fulfilling lifetime career.

While it is full of names known only to dedicated cinephiles, there are many others that are widely recognizable. The author describes his encounters with Gloria Swanson, Marcello Mastroianni, and Roy Cohn, among numerous others.

The depth of content becomes accessible through the volume's organization. It is divided into 11 parts, ranging from "Unsung Film Pioneers" to "Directors [and More Directors] in My Life" to "Portraits" (of some significant contributors to cinema) to "Upper West Side Cinemas." In the section called "Acquisitions" there is a chapter on the 1981 cult film "My Dinner With Andre," the success of which Mr. Talbot had an impact upon.

Most chapters are short and concentrated. Longer than many of them is the letter Mr. Talbot sent to the estimable New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael, about her negative reactions to "Shoah," Claude Lanzmann's 1985 French documentary about the Holocaust. The single bad review of the film was Ms. Kael's. Mr. Talbot took her overwhelmingly to task, something most other mortals would not have been quick to do, given the influence she wielded.

One takeaway from this memoir is that authentic devotion to an art form engenders taste and an appreciation of quality, rather than snobbery. Another is that such devotion can make for a life well led.

Following the author's text, there is a loving epilogue by Toby Talbot, his wife and editor. "Our Lincoln Plaza Cinemas are no more," she writes. "Closed on January 28, 2018. After almost forty years. . . ." The last films shown there included "Happy End" and "Darkest Hour."

Mr. Talbot had died just a month before. "It was my darkest hour," she writes. "Gone, my dear husband of nearly seven decades."

A cinematic ending, some might say.

Jim Lader, who owned a weekend home in East Hampton for many years, has reviewed books for The Star since 2009.

Daniel Talbot had a house in Water Mill.