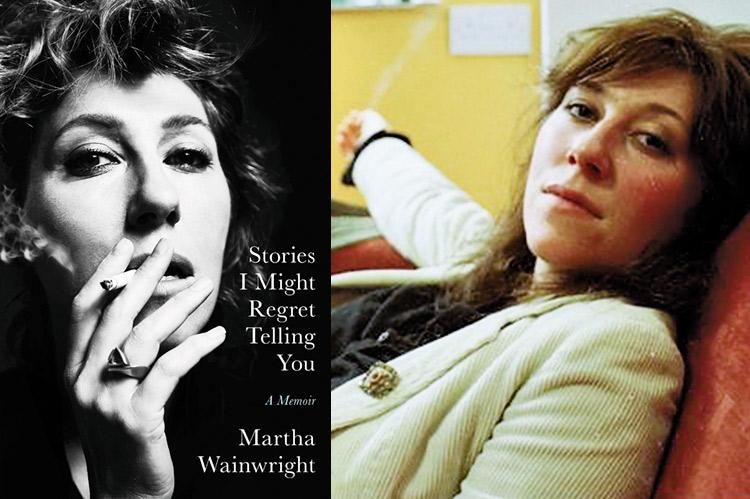

“Stories I Might Regret Telling You”

Martha Wainwright

Hachette Books, $29

Perhaps best known for her breakout song "Bloody Mother Fucking Asshole," Martha Wainwright's career as a singer-songwriter has grown up from the soil of her childhood. Sister to a well-known musician, Rufus Wainwright, and daughter of the storied American singer-songwriter Loudon Wainwright III and the beloved Canadian folk singer-songwriter Kate McGarrigle (of the McGarrigle Sisters), she notes, "For better or for worse, music is the family business."

This relationship to music, to her brother, father, and mother, and to better and to worse, is the nexus for Ms. Wainwright, who delivers the contours of her complex family, and her family complex, beginning on page one of her memoir.

She tells her story with an easy tone and a smattering of witty one-liners, cool like lines to a song. She writes with an explicit awareness that the reader has come for the inside scoop on the Wainwright/McGarrigle musical dynasty, which is complete with multiple generations of musical success and a deep bench of extended in-family musical talent that ranges over divorce, reconfiguration, and international lines. Ms. Wainwright's family legacy reads as extravagantly eccentric, brilliant, and well connected to the music industry.

Meanwhile, she is crystal clear on her sense of insecurity within the overwhelming allure, talent, intelligence, and notoriety of her family members. The title of the volume, "Stories I Might Regret Telling You," is both provocation and hedge, encapsulating the dual urges she rehearses throughout the book: to be seen and to protect herself from various pitfalls, including impending failure, or, much worse in her world, lurking mediocrity.

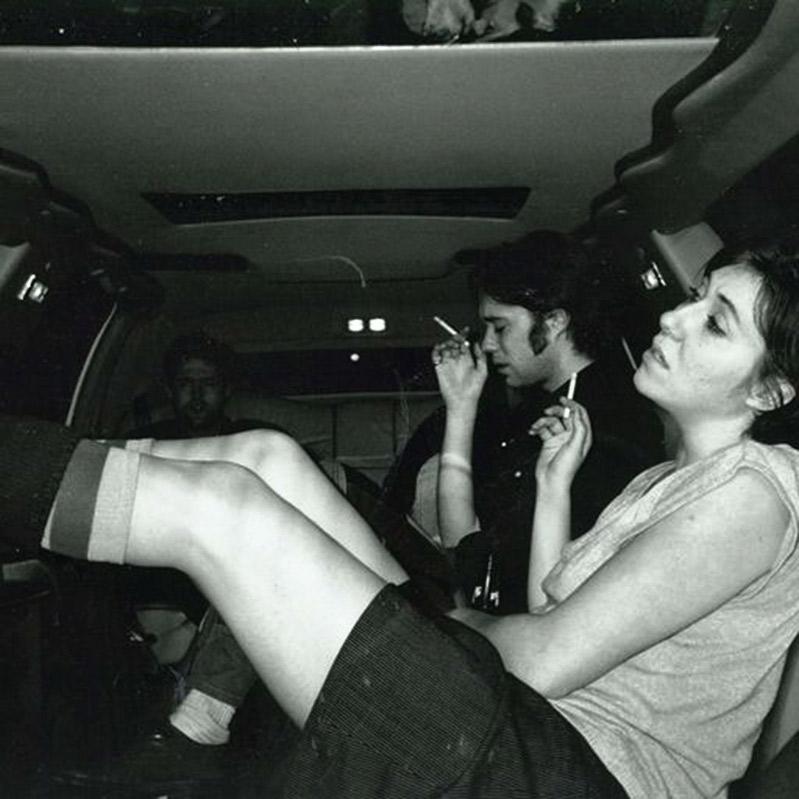

Bring on the exhibitionist flash of a celebrity daughter, revealing low self-esteem with plenty of self-sabotage in the form of reckless depravity around drugs and alcohol and much flirting with unsuitable relationships. Add in copious name-dropping of famous musicians and the like, and what could be termed experience-dropping (e.g., accidentally surprising Madonna getting dressed in a bathroom), and you've got a credible tell-all, though Ms. Wainwright's almost naive prose gives the book an unexpected wholesome, innocent quality, given the level of self-destructive behavior she is recounting. Insights into her own motivations are offered casually, as if caring too much, or seeming eager, even from the safety of the distance of time, is to be avoided like a poor slant rhyme.

Much of the book is set against the backdrop of the later 1990s and early to mid-2000s sex, drugs, and rock 'n roll scene in New York and London, during which Ms. Wainwright was surely, to use the technical term, a hot mess. Yet she paints a picture of musical projects that put her on the map in her own right and friendships that endure. She was able to accept mentorship and work with other musicians successfully. There's the feeling of an underlying, if obscured, solidity of character.

Numerous personages are mentioned here, including Rufus, her brother, at whom she takes many swipes: sibling stuff with a dramatic flair to match the fame, but zero intent to harm. Loudon, her father, plays a part but feels remote, and Kate, her mother, comes across as a charismatic woman, her supporter and champion, though the edge of self-absorption comes across, too.

Though Ms. Wainwright's former husband, who is the father of her children, is a frequent figure in the book, beginning with their meeting in New York, no real sense of him emerges. One feels a hole in the fabric there, but Ms. Wainwright creeps into your heart with her unpretentious style — you are rooting for her — and if the former husband is a story she would really regret telling, better that she exercise caution than succeed as a killer memoirist.

A distinct tenderness appears in the writing toward the end of the book, as she recounts her mother's cancer and subsequent death in 2010. She brings love and reverence to the loss of the stunning, inimitable, key figure in her life, whose death overlapped with the difficult premature birth of her first child. A devastating end and a miraculous beginning played out in tandem; the author captures that with honesty.

There is a sense of arrival in the epilogue, where Ms. Wainwright is on the other side of her mother's death and a painful divorce. She's embarking on new ventures; she's devoted to her children. Perhaps she is moving from the shadow of her family and finding some interesting patches of sunshine, too.

Evan Harris is the author of "The Quit." She lives in East Hampton.

Martha Wainwright's extended family has roots in East Hampton, and her father, Loudon Wainwright III, lives on Shelter Island.