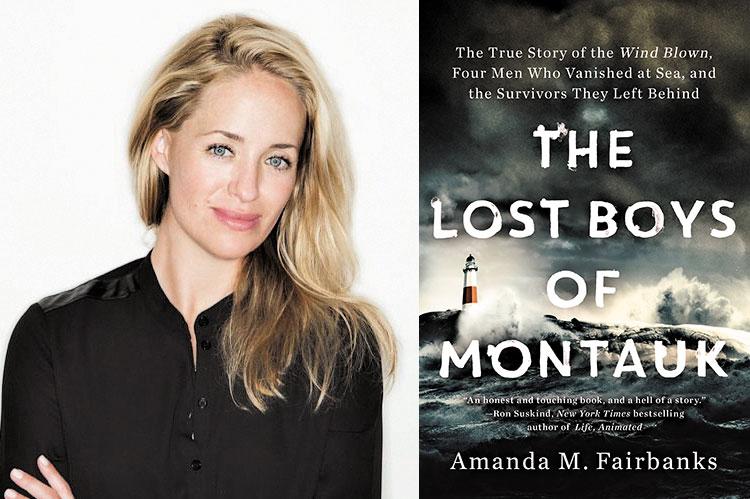

“The Lost Boys of Montauk”

Amanda M. Fairbanks

Gallery Books, $28

Why should we care about four men who drowned 37 years ago? As I read Amanda Fairbanks's new book, "The Lost Boys of Montauk," I asked myself this question, but only occasionally, because the prose moved fast and promised to expose secrets, and the rawness of the story pulled me along like an unrelenting undertow.

Ms. Fairbanks grew up in California and worked for a time as a reporter for The East Hampton Star. An editor told her that the tragic disappearance of the Wind Blown and its crew in March 1984 was "one of the great untold stories of the Hamptons" and deserved a more thorough telling than it had received. Ms. Fairbanks was intrigued and eventually took the bait. She interviewed family members and friends of the victims, traveling as far as Hawaii to do so, read source documents, studied trauma, and even tracked down a recommended shipwreck expert through online fishing forums.

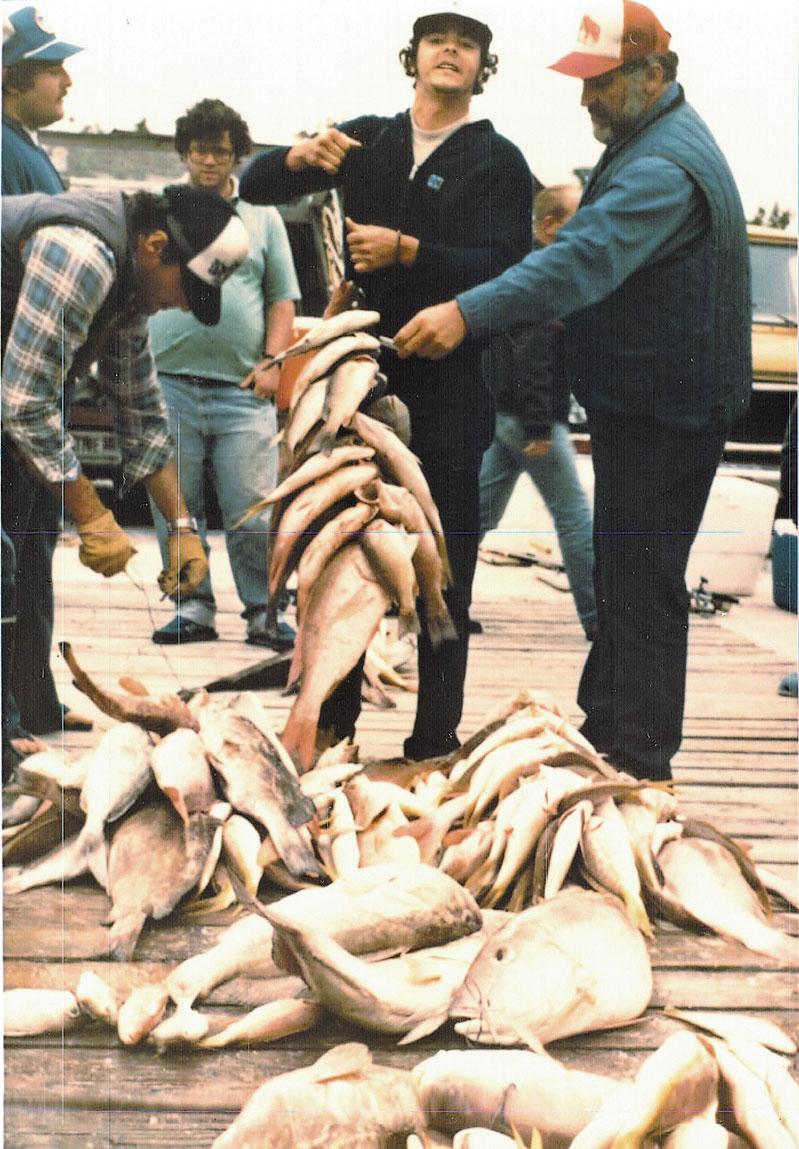

The result is a book with a broad reach, and many residents of the East End will find a connection to the material through the people and places mentioned and local stories told. "The Lost Boys of Montauk" is not "The Perfect Storm II." In addition to all we learn about fishing and a working life at sea, there is much history and nuance about landlubbers.

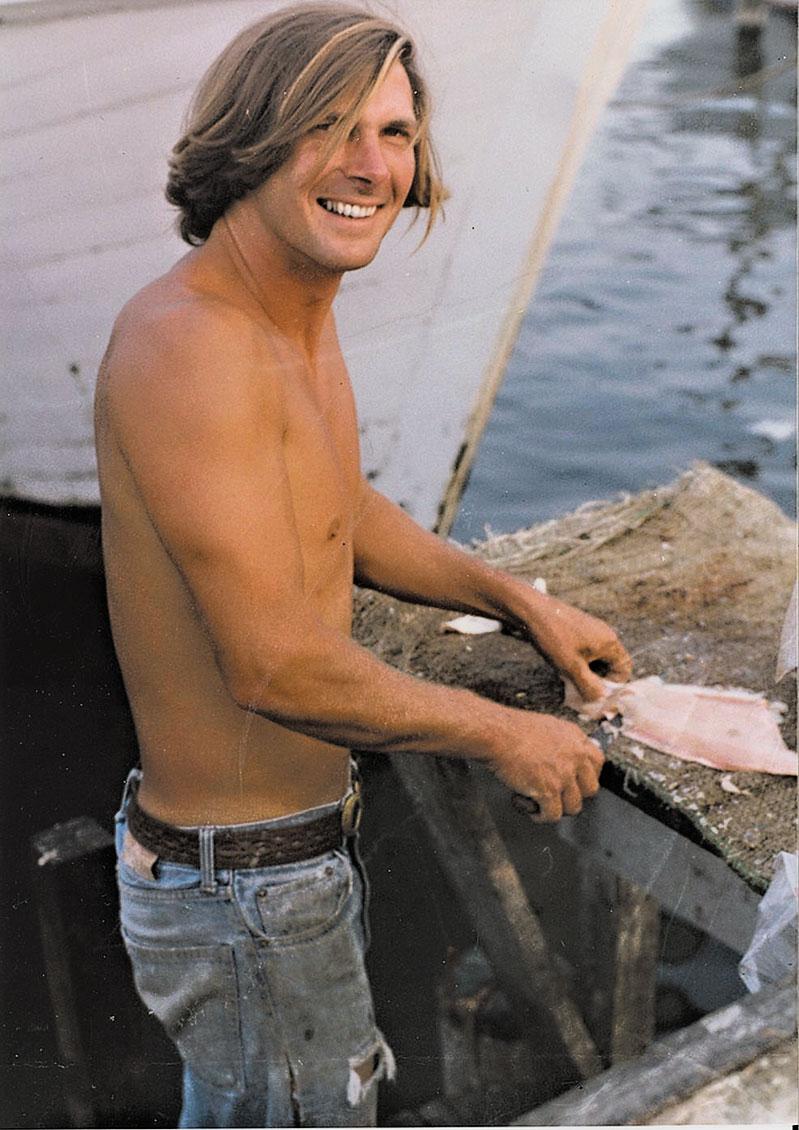

The author's expansive view of what kind of telling the story needed came home to me in Chapter 4, where I found mention of the family who introduced me to the South Fork, back in the 1970s, when a college friend and his brother were part of "Mahoneyville" — a Georgica Beach surfing and friend group that included David Connick, a charismatic young man who had taken to the water from an early age.

From the perspective of craft, the author faced a challenge. The "action" is over early. The first paragraph has Connick and three other men boarding the Wind Blown in Montauk in late March 1984. They are off to catch tilefish, a lucrative way to spend a week. By page 14 a freak storm has assaulted the western Atlantic, and by page 17 we read the East Hampton Star headline: "Fishermen Feared Lost in Storm Off Montauk: The Town Is Battered."

With such drama and near-finality early on, what propels the narrative for the next 275 pages? Mostly blame, grief, and the compelling nature of disaster, especially one occurring in a place as foreign to most of us as the deep sea. Ms. Fairbanks feeds our fascination with the watery world and writes with well-researched understanding about the lives of commercial fishers, especially the close-knit fishing community of Montauk that gave the men on the Wind Blown a way of life they loved, albeit for too little time.

Yet just as the author describes the profound lack of closure for family members arising from the victims' bodies not being found, there is a lack of definiteness to the Wind Blown's fate that no amount of research can solve. Did the captain, Mike Stedman, stay out too long after storm warnings, did he make an error in judgment while navigating, or was the cause of the wreck his choice of a top-heavy, low-quality vessel?

Alternatively, was there a rogue wave so massive that no boat, no matter how well constructed or piloted, could have withstood it? We will never know. There are no witnesses, black box, or cellphone video. There is only speculation.

And so, Ms. Fairbanks takes us on a long trip into the four men's backgrounds, an examination of how they came to be on the Wind Blown on the deadly day of March 29, 1984. Life shows time and again how random acts and seemingly unrelated decisions can mean the difference between life and death, and this is painfully illustrated by the happenstance that one of the mates, Michael Vigilant, was a substitute for the usual fourth crew member who had decided at the last minute to go surfing in the Canary Islands.

But where does one stop? Was every aspect of the victims' lives, every choice made by their parents and grandparents, mere prelude to the four men's final voyage on the Wind Blown? Readers are likely to reach different conclusions about the value of some of this material. Ms. Fairbanks also faced an imbalance of information in that Stedman and Connick had family histories that were better documented than those of Vigilant and Scott Clarke. Nonetheless, she clearly sought to give each man as full and sensitive a telling as possible.

There are passages in "The Lost Boys of Montauk" of stunning beauty. The book is at its best in showing the long-lasting impacts of the men's disappearance on their spouses, lovers, parents, children, friends, and members of the Montauk fishing community. The tributes that people continue to make for the men are affecting, an uplifting reflection of the depth of human bonds. As Ms. Fairbanks eloquently writes toward the book's end, "grieving is the last way we get to love someone."

The men were at the beginning of their adult lives' arcs. They worked with their bodies in a place and profession that emphasized physicality, and a good amount of their leisure time was spent surfing, partying, and loving. The sensuality of their lives as illustrated by Ms. Fairbanks makes their loss seem especially palpable.

One hopes that the late Janet Malcolm was not universally right when she wrote in "The Journalist and the Murderer" that it is fundamentally irrational to speak to a reporter. A number of Ms. Fairbanks's interviewees likely felt some catharsis going back in time with her, for her strong interest and research allowed them to reflect on a traumatic and pivotal period in their lives in a rare way. Nonetheless, some of her subjects do seem to have had second thoughts, and others may wish they had demurred when they see that their accounts were challenged by others.

Stedman's eldest son is reported to have assured Ms. Fairbanks that he wanted to cooperate because he believed in her "authenticity." At points, however, we learn details about people's personal lives that perhaps could have stayed confidential. These are not public figures, but private people drawn into a public tragedy decades ago. The author had to make difficult decisions about what to include and what to exclude, and presumably she did so in good faith, believing the full story required candor.

There is something to the idea of a community needing to get a collective lump out of its throat, and perhaps there needed to be no holding back for that to happen. Or maybe my reading is wrong, and there was even more sensitive material that Ms. Fairbanks decided to withhold.

Ms. Fairbanks means us to grieve not just for the men, but for a lost way of life, and a lost place. She devotes much of the book to laments that Wall Street money and young partiers have changed Montauk and the East End forever. She gets to this subject because Connick was from a well-off "second home" family, the product of private schools and boyhood days at the Maidstone country club. She wants us to regard the four "lost men" as a metaphor for the Montauk that was — before big money moved in — but the East End has much more diversity than fishers and financiers. There are many in between those poles, the teachers, artists, musicians, writers, scientists, nonprofit staff members, paralegals, landscapers, farmers, shop owners, self-employed professionals, and retirees who have chosen this place because they love the water, the light, and the astonishing beauty that still exists.

And while nostalgia for the pre-traffic, freewheeling days of the 1970s is understandable, community involvement and activism have done much to sustain the best of the East End. Since the 1980s, voters have time and again approved measures to preserve land, and nowhere on Long Island has land protection been more successful than in Montauk: An impressive 60 percent of the area is protected from development. From that perspective, Montauk is not lost, it is saved.

The dark skies movement, government buyouts of properties vulnerable to sea level rise, large investments in restoring water quality, the new Long Island Wildlife Monitoring Network, and the planting of pollinator gardens are but a few of the ways in which people on the East End are coming together to protect our lands and waters and abate the influences of money, poorly sited development, pollution, and climate change.

"The Lost Boys of Montauk" shows how complicated death can be, especially traumatic, early death. The book can only expand readers' compassion for the survivors of loss and appreciation for the impacts our choices have on others. The deaths of Mike Stedman, David Connick, Michael Vigilant, and Scott Clarke were a tragedy, but let us not despair over the loss of the East End, not yet, anyway.

Marian E. Lindberg is the author of "Scandal on Plum Island: A Commander Becomes the Accused." A lawyer and land protection specialist, she lives in Wainscott.

Amanda M. Fairbanks lives in Sag Harbor. She will discuss her book at Guild Hall on July 11 at 4:30 p.m.