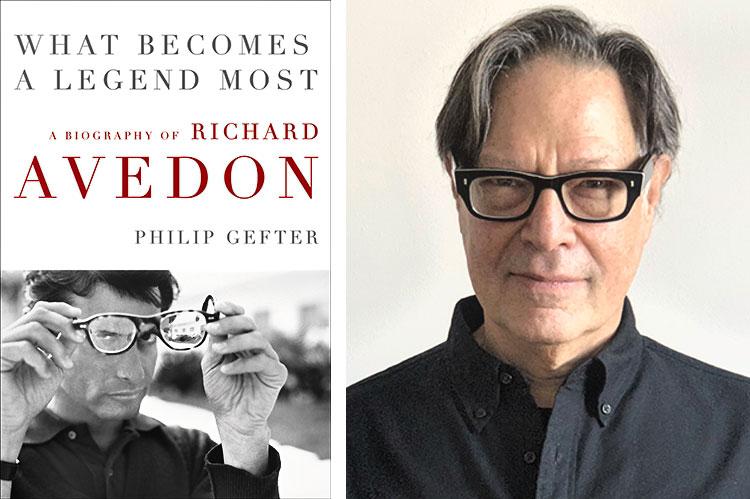

“What Becomes a Legend Most”

Philip Gefter

Harper, $35

Is this book's title a question? Or could we ask: What is it about Richard Avedon the man, or about Avedon's work, that would make him legendary? As Philip Gefter tells it in "What Becomes a Legend Most," he was physically a slight man but made an impression that was larger than life, and his work is more than well known, it is eminent.

My reading left me with a sense that the man was tragic. Driven by the insecurities of a second-generation Jewish family and an undistinguished education, he wanted material success and he also wanted recognition as a great artist. "Dick always had his eye on the prize, and that was greatness."

He accumulated substantial wealth by taking photographs for commercial use, but he resented the disdain of the "official" art world toward his noncommercial work.

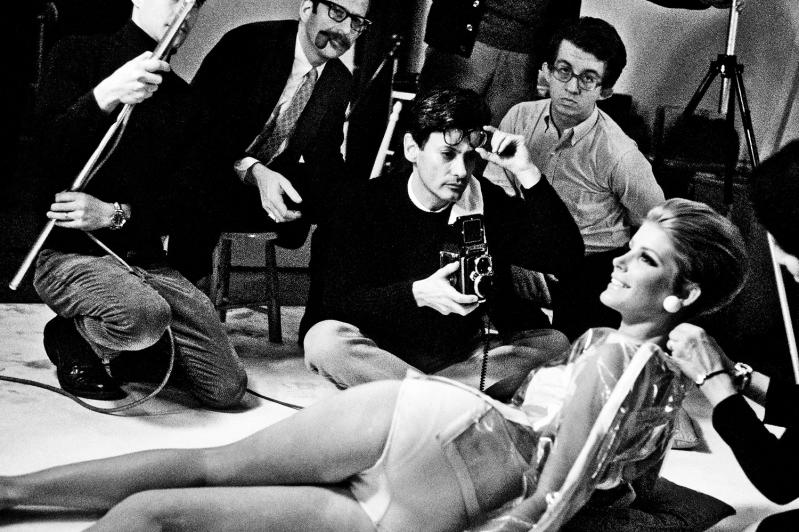

To begin with, the art world did not consider photography to be a legitimate part of its realm until late in the 20th century, finally anointing 19th-century artists like Nadar in retrospect. So it was already a tough gate to crash. And then, Avedon's early work for Harper's Bazaar and then Vogue, for Carmel Snow and Diana Vreeland, respectively, was in the service of fashion, albeit of the most exclusive kind.

John Szarkowski, MoMA's curator of photography, "refused to acknowledge [Avedon's work] because his artistic imperatives were obscured by the glitz of his commercial prominence." Perhaps resentment is not a sufficient word. I have come away from this biography with the impression that Avedon was inconsolable over this disdain. Mr. Gefter gives us numerous extended descriptions of Avedon's lifelong efforts to overcome it. When Avedon turned to making art, his subject was portraiture for which he became as famous as for his stunning fashion illustrations.

Eventually he got one-man museum shows at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the University Art Museum in Berkeley, Calif., the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Tex., and finally the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1994, by which time he was over 70 years old. Later there was a major show at the Met in 2002 and posthumously at Guild Hall in East Hampton in 2017. But never at MoMA, the be-all and end-all cathedral of modern art.

Controversy remains over the artistic value of Richard Avedon's work. For some leading critics (commenting on the Whitney show), he is a master: Philippe de Montebello, the Met's former director, wrote in The Times that "Just as Nadar made telling portraits of rare individuals and in doing so captured the creative genius of his generation, so Avedon, a century later, collected the key players and directed them in a brilliant portrait of an era that is questioning, unruly and self-consciously alive. . . ."

For Michael Kimmelman, then chief art critic at The Times, "The problem is that the theatricality of Mr. Avedon's portraits isn't absorbing . . . they are too hollow to constitute ART."

Avedon's pre-eminence as a fashion photographer is undisputed. Who doesn't remember "Dovima With Elephants, Evening Dress by Dior, Cirque d'Hiver, Paris," first published in the September 1955 issue of Harper's Bazaar? It is the portraits that invite controversy. They are described here as "stone-cold, corpse-like representations of individuals," or, as Time magazine had it, "Avedon is possessed of a lens that is a subtler, crueler instrument of distortion than any caricaturist's pencil."

Mr. Gefter's judgment is that Avedon's "intention was not to get at human emotion or to render the human connection between subject and photographer; rather, his vast project of photographing individuals as specimens of a species [italics mine] was a forensic exercise in visual contemplation as much as an aesthetic determination to achieve the highest resolution that could be had from the medium."

"His photos from the last two decades are increasingly the work of a despairing, often pessimistic social observer," Vince Aletti wrote in The Village Voice, "a man who sees, finally, through life's sad, corrupt masquerade."

Avedon's own words concerning his work are revelatory. "A portrait is not a likeness. The moment emotion or fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion. All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth."

"I trust performance . . . the way someone who's being photographed presents himself to the camera and the effect of the photographer's response on the presence is what the making of a portrait is about. . . . The surface is all you've got."

"My photographs don't go below the surface. They don't go below anything. They're readings of the surface. I have great faith in surfaces. A good one is full of clues."

"Photography for me has always been sort of a double-sided mirror. The one side reflecting my subject, the other reflecting myself."

"All my portraits are self-portraits."

When asked if he thought he had stolen something from his subjects, he said, "Stealing implies a crime. No harm is done here. I've just recorded their faces in the way I see them. I give it my soul, and they give it their surface." That's pretty tough stuff, it seems to me. We are back to the Daumier caricature analogy.

I remember attending the Whitney show in 1994. I was struck at the time that the wall-size enlargements of the portraits did seem "stone-cold, corpse-like," as if they were giant butterfly specimens pinned to a wall. Only Groucho Marx, "balding, black-sweatered, solemnly dreaming of something off-camera" (italics mine), seemed to have escaped Avedon's tyranny; he looked to me very much alive and defiantly amused.

There is much, much more to this biography. Lots of interesting stuff and fascinating people in its 570 pages that I will leave to the reader to discover. But to sum up, the portent of this book is framed by Emily Dickinson in a poem Mr. Gefter uses as a foreword:

Fame is a bee.

It has a song —

It has a sting —

Ah, too, it has a wing.

Readers can see and study many Avedon images at the Richard Avedon Foundation website under the heading "the work."

Ana Daniel is retired from business and teaching. A regular book reviewer for The Star, she lives in Bridgehampton.

Richard Avedon had a house in Montauk for many years. He died in 2004.