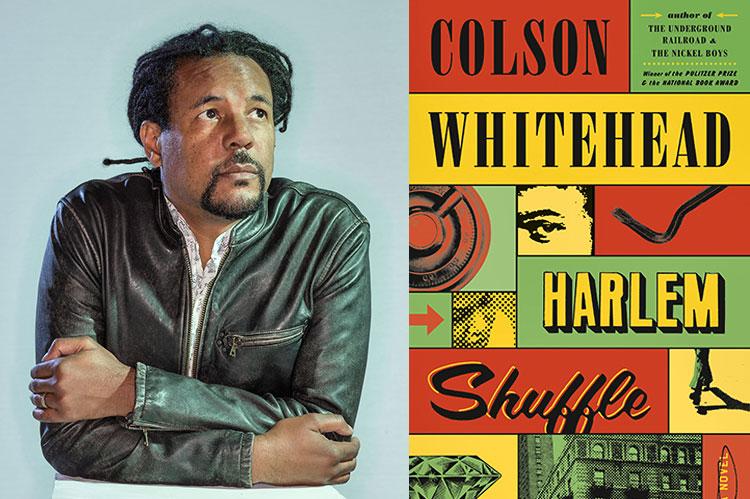

“Harlem Shuffle”

Colson Whitehead

Doubleday, $28.95

For the record, I am a Colson Whitehead dissenter. That is, I am a big fan of his first two, mostly unloved novels: "The Intuitionist," a dystopian noir about an elevator operator, and "John Henry Days," in which a middling Black journalist juxtaposes his life against the mythic African-American hero John Henry.

Conversely, I was the one reviewer in America — maybe on planet Earth — who thought "The Underground Railroad" was a fascinating experiment that didn't quite hold together. And I still carry the shame of knowing that with a swipe of my pen I derailed a promising young writer's career . . .

Well, not really. "The Underground Railroad" went on to sell millions and win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, as did his next novel, "The Nickel Boys." Back-to-back Pulitzers? Apparently, he survived.

Now comes a new novel, "Harlem Shuffle," and I have bad news for its publisher and Mr. Whitehead's bank account. I like this one a lot.

Set in uptown Manhattan in the early 1960s, the novel tells the story of Ray Carney, an African-American furniture salesman trying to move his middle-class family up the financial ladder. Ray is good-natured and generous to a fault, offering layaway plans to struggling Black families and showing an undeserved blood-loyalty to his cousin Freddie, a ne'er-do-well who occasionally shows up at Ray's shop with merchandise that apparently "fell off a truck."

Carney is one of the best characters Mr. Whitehead has ever written, almost inexplicably likable, given all his frailties. He knows a jeweler downtown, Moskowitz, who is willing to fence some of Freddie's items, with Carney taking a small kickback. It's this relationship, mostly harmless on the face of it, that gets Carney entangled with some more serious criminals. You know, for example, that when people with names like Chink Montague, Yea Big, and Miami Joe begin to drop by your furniture store, they're probably not looking for a china cabinet.

Mr. Whitehead is someone who loves to delve into different genres — he can seemingly do just about anything (he's also written a zombie novel and a book about poker). He seems like the kind of author who reads writers in different genres and says, "Hey, I'd like to do something like that."

At times, "Harlem Shuffle" recalls the work of Walter Mosely and James McBride, two other African-American novelists who work with urban noir themes. Mr. Whitehead's lens, however, is wider than those writers'; it's as if others shoot on digital film while Mr. Whitehead is working in 35-millimeter.

"For most of the day the hotel lobby bustled like Times Square, guests and businessmen crisscrossing the white-and-black tiles, locals meeting for a meal and gossip, their number multiplied by the oversize mirrors on the green-and-beige floral wallpaper. . . . At night, swells congregated in the leather club chairs and sofas and smoked cigarettes as the door to the bar swung open and shut. Porters ferrying luggage on carts, teams of clerks at registration handling crises big and small, the shoe-shine man insulting people in scuffed shoes and arguing for his services — it was an exuberant and motley chorus."

This, along with other depictions of the New York of this era, seems dead-on. And it's fun watching the writer bluff his way through the lingua of a department store furniture salesman, something he spends an inordinate amount of time on in "Harlem Shuffle": "Now the customers were going Argent, with those clean lines and jet-set emanations. Take that Airform core, zip it up in the new Velope stain-resistant fabric — they really knocked it out of the park." Pure baloney, but it works.

Similarly, there are two different heists in "Harlem Shuffle," both carried off with a satisfying verisimilitude. Mr. Whitehead understands, of course, that in fiction a heist is not a heist unless something goes terribly wrong.

Carney's wife, Elizabeth, isn't particularly distinctive, but almost every other character is well drawn — none less than Miss Laura, a reluctant prostitute who helps Carney get revenge on a swindling Harlem elite. Miss Laura recalls how she arrived at the New York apartment of an Aunt Hazel trying to escape a dreary life in North Carolina.

"She's the one that got me working at Mam Lacey's — you know it?" Carney says that he does. "I didn't work downstairs."

In the bar, in other words. "Right," he replies.

There is also a soaring passage, albeit late in the book, where we get Freddie and Ray's back story. It is a touching remembrance of childhood innocence, and goes a long way to explain Ray's blind loyalty to Freddie. It also shows life as a crapshoot of good and bad breaks, of which the cousins occupy opposite sides.

Obviously, a novel set in Harlem in the early 1960s will have its fair share of racial politics. Mr. Whitehead mostly deals with this with his usual deft hand, integrating events like a police shooting of a Black youth neatly into the seams of the plot.

There is, however, the occasional false note. For instance, a local bartender says of America, "This whole country's founded on taking other people's shit." Is this meant to be the half-baked cynicism of a marginal character, or are we to understand some authorial voice here? Either way, it comes off as a little glib.

In the novel's resolution, Carney decides that, despite some of the bad guys having gone down, nothing has really changed, "black boys and girls continued to fall before the nightsticks and pistols of racist white cops." There is the pith of truth in the statement — there is the ugly killing in 1964 of James Powell, a 15-year-old, for example, and the subsequent riots, from which this novel borrows.

But this also traffics a careless hyperbole. One murder is too much, obviously, and there were probably others, but if the statement is suggesting that the murder of Harlem's Black youths in the early 1960s at the hands of police was habitual and voluminous, then it is misleading. It is not too much to ask of a great writer, I don't think, to be less blithe on combustible topics, even if the opinions come from the mouths of their characters.

Writing this, as he must have, during and after the George Floyd murder, it is understandable that Mr. Whitehead wanted to give his novel an urgency beyond a "mere" corker of a noir. There is even an unprecedented message on the cover of the reviewer copy I received, where he addresses the reader directly, in a sort of apology, stating that "Harlem Shuffle" is a "change of pace." He adds, almost unctuously, "I'm crossing my fingers that you enjoy this one as well." As if this were an embarrassing toss-off!

In fact, with its grand depiction of a lost New York and sharply drawn characters, "Harlem Shuffle" is one of Colson Whitehead's best and certainly most enjoyable novels. Nothing, I'm sure — not even an endorsement from me — can sink it.

Kurt Wenzel is the author of the novels "Lit Life," "Gotham Tragic," and "Exposure." He lives in Springs.

Colson Whitehead lives in Manhattan and Sag Harbor.