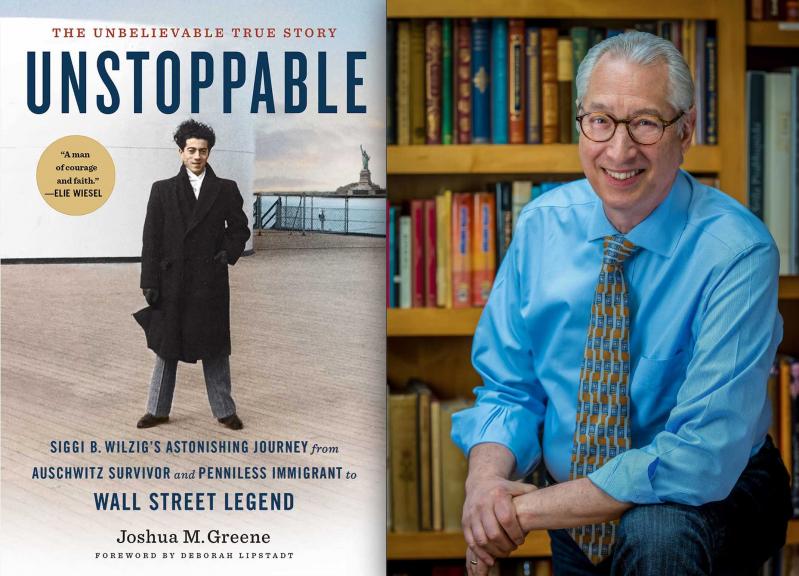

“Unstoppable”

Joshua M. Greene

Insight Editions, $29.99

A toddler in the early 1950s, I crossed the Atlantic with my parents on a boat from Bremerhaven, Germany, just a few years after a 21-year-old Siegbert Wilzig made the same journey to America. He defied Hitler, as my parents had, by remaining alive. Like my mother, he passed through Auschwitz on the way to liberation.

In 1981, at the first World Gathering of Holocaust Survivors in Jerusalem, I met many such refugees, settled in many lands, and learned an inalienable truth: Some survived better than others. Not the broken, nightmare-ridden character of Rod Steiger's "The Pawnbroker," by every standard, on a scale of 1 to 10, "Siggi" Wilzig was a 10+, the "unstoppable" of "Unstoppable."

To learn about their pasts, to defend against Holocaust deniers, families have asked their loved ones to go back to this memory, of life before, to rewitness the murder of mothers and babies. Each story unique, the Holocaust survivor memoir — published or not — is a significant genre: Steven Spielberg's influence in collecting testimonies for his Shoah Foundation and Visual History Archive platforms, funded by his 1993 "Schindler's List" success, is important, formidable, as is the imperative: Never again.

Storytelling becomes its own heroic act because, in the aftermath, no one could speak of it, no one could listen, no one could believe it. My family took the more passive stance of silence; better to leave the children to a fresh new world. Siggi Wilzig was loud, an activist, and he left his family much more than a Holocaust legacy.

Wealthy — surely the only ones with a castle in Water Mill — Wilzig's family did him a great service by connecting with a real writer with real Holocaust credentials: Joshua M. Greene, an Old Westbury resident and noted film documentarian and lecturer who has written several books, including "Justice at Dachau." When Siggi's son Ivan contacted Mr. Greene, he refused at first, claiming he was finished with writing about "darkness," but then Ivan persuaded him, saying his father was a beacon of "light, inspiration, and hope for humanity." Anticipating the book would take 18 months, Mr. Greene worked on it for seven years.

A well-researched biography, "Unstoppable" limns Siggi's braggadocio, outsized swagger (he was 5-foot-5), and black humor, addressing an oft-asked question: How did anyone survive?

To read Siggi's story is to see how even luck requires talent. A friend got him to "Canada," the least horrible place to work in Auschwitz. Using his wits and wiles, lying, he worked jobs — doctor's assistant, mechanic, laundry worker — for which he had no aptitude. Faking it hard gave him the next day.

Like Elie Wiesel, whom he later befriended, he saw his father die: "To have found my father in there was more than a minor miracle," he is quoted as saying. The next day, his father was dead after eating poisoned potatoes.

But these were just Siggi's salad years, outsmarting Nazis and then coming to these shores, landing in New Jersey and outsmarting American gentiles. The remarkable part of Siggi's story is killing it in industry, reviving companies in oil and banking, his business acumen, his deal making, and, despite everything, his sustained passion for Judaism. He showed up in Texas boardrooms, brandished his tattoo, and told self-aggrandizing/self-deprecating jokes.

What chutzpah! And yet, to be fair, midcentury America was tough for immigrants, for Jews. Embarrassing, pushy, and disarmingly charming, in business Siggi was, as one friend said, someone no one could say no to.

And then there was Bitburg. Mr. Greene is very good at describing the triggering for Siggi's Holocaust tics: Blemished bananas would send him reeling, reminding him of rotting food. But his outrage over President Reagan's insistence upon visiting the cemetery at Bitburg for a political accord with Chancellor Kohl, a protest shared by Wiesel and many survivors, sent him into despair: Nazis had been interred there. Insensitive to the survivors' concerns, Reagan proclaimed that the S.S. were victims too.

Really? Jewish community leaders, Siggi among them, attempted to reason with Reagan, to no avail. This callous affront was huge. Siggi had been lecturing at top universities about his past; he boasted of being the first survivor to address the cadets at West Point. Disheartened that an American president could equate the experience of victim and perpetrator, Siggi stopped lecturing for a dozen years after that betrayal.

An emotional talker, Siggi's English could echo the inflections of Borscht Belt comedians. At the opening of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, an event attended by President Clinton and the Dalai Lama, Siggi kibbitzed from the front row. "Do you know which car is the best car in the world? A Mercedes. Not once did a Mercedes vehicle break down delivering Jewish children to the ovens of Auschwitz."

No surprise, Siggi was a big fan of Jackie Mason. For his 70th birthday, his family bought tickets to see the comedian on Broadway, and the next night at dinner at Le Marais, a kosher theater district steakhouse, the two men vied for who was the funniest Jew at the table.

A proud parent of his Ivy League-educated children, Ivan, Sherry, and Alan, Siggi was rigid about their friends, who they dated, every decision. Children of survivors could not bear to hurt them further. The novelist Melvin Bukiet described the "cosmic responsibility": "Other kids' parents loved them but never gazed at their offspring as miracles in the flesh. . . . How could you rebel against these people who endured such loss?"

No matter where he was, he could not let anyone forget the story, so overwhelming no other story was possible or mattered. Siggi's wife, Naomi, was left in the shadows; at dinners, couples found it surprising that she had a personality at all. By 2000, they were living apart but never divorced. She went on to found the World Erotic Art Museum in Miami.

I would not have met Siggi at that world gathering in Israel in 1981. He never went to the Holy Land; like my father, he excused himself to watch over the business. But he gave back in his charities, dined with presidents at the White House, obsessively kept memory alive even when it pained him to revisit Auschwitz, the hell he never quite left.

Read this compelling book, for Siggi's heroic struggle, for financial tips on how to invest or broker a deal, and in this untoward time for immigrants — to see the American Dream in action.

Regina Weinreich is the author of "Kerouac's Spontaneous Poetics," editor of "Kerouac's Book of Haikus," and co-producer/director of "Paul Bowles: The Complete Outsider." She lives in Montauk and Manhattan.

Siegbert Wilzig died in 2003.