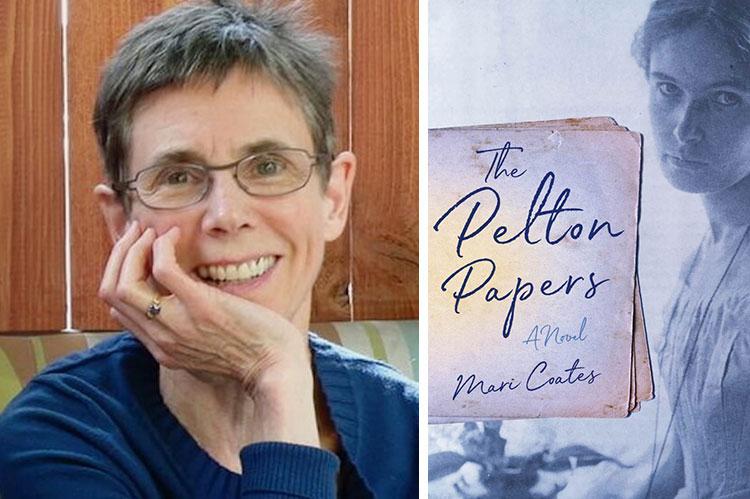

“The Pelton Papers”

Mari Coates

She Writes Press, $16.95

Almost a year ago, the Whitney Museum of American Art announced its spring 2020 exhibition of Agnes Pelton paintings. Her works would introduce “to the public a little-known artist whose luminous, abstract images of transcendence are only now being fully recognized,” promised Artmap.com. “The times have caught up to the color-drenched mysticism of the American painter Agnes Pelton,” reported The New Yorker in its March 9th issue.

Then the times were upended. On March 13th, the very day its run was set to begin, the coronavirus national emergency was declared, the museum immediately closed, and all events were canceled. But a sort of substitute would soon appear in the form of Mari Coates’s impressive new book, transcending to a degree the spring disappointments.

“The Pelton Papers” is subtitled “A Novel.” Yet it is more than a made-up narrative. Rather it is the story of a real person, told by the author through imagined thoughts, acts, conversations, and even dreams that the person relates, and which are based on real events involving other real persons. Ms. Coates presents this clearly and convincingly.

A core element of “The Pelton Papers” is the Agnes Pelton Collection of historical materials at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. Ms. Coates’s references include scholarly studies, and there are research institutions credited where she gained information and insights. Alternate fonts are used to indicate actual quotations. The author has thereby grounded what might be considered a fictitious autobiography in factual sources, and contextualized in facts her interpretation of Pelton’s life.

Agnes Pelton’s early years were difficult though rewarding. The small, bronchitis-susceptible only child of parents who periodically separated, she both sensed family tensions and instinctively appreciated the beauty of natural surroundings. Initially these were in European cities, such as Stuttgart, Germany, where she was born in 1881.

William Pelton and Florence Tilton, married the year before, each had fled unbearable situations at home. He originally came from Louisiana, then New York City. Neither post-Civil War Terrebonne Parish nor the nation’s metropolitan center suited his unstable temperament. But southwestern Germany, where his sugar merchant father lived, offered an alternative. It also happened to be where Florence was studying piano, violin, and music theory at the Stuttgart Conservatory.

For Florence, studying music abroad was a career move as well as an escape from scandal. In 1874, her mother, Elizabeth Tilton, had an affair with the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher of Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights. “Criminal intimacy” charges against Beecher were brought by Elizabeth’s husband, a top associate of the minister and colleague in publishing Beecher’s widely circulated journal, The Independent. This led to a sensational trial at which Florence testified. In Agnes’s telling, decades later: “She had intruded upon her mother and their family minister, found them in a compromising position, and frightened, had told her father about it.”

After six months the jury could not reach a verdict. Beecher was partially exonerated, whereas the women suffered unending humiliation. Elizabeth confessed, grew more devout, and “swathed herself in black and became a penitent recluse.” Florence tried to repress terrifying memories by concentrating on music lessons that she conducted. Agnes would take advantage of opportunities for personal and professional development. Still, 20 years after Elizabeth’s death, and decades since the event, a Brooklyn Eagle article about Agnes was headlined: “Local Artist Is Granddaughter of Beecher Paramour.”

“The history of who my grandmother was, and by extension who my mother and I were . . . the heaviness of our common past” lifted after Florence died, when Agnes was 39. “Closing my childhood chapter,” she decided to leave Brooklyn in favor of quiet and solitude, “to immerse myself in the natural world . . . in eastern Long Island.”

This chapter proved consequential in various respects. After spending the summer of 1921 in Southampton Village, she learned that the no longer operating Hayground windmill might be available to repurpose for living space and a studio. The owner and ex-miller was reluctant but finally relented, agreeing to interior modifications. Agnes envisioned: “Me . . . alone and loving all of it, from the ecstasy of solitude to the sharp anticipation of a season alone.”

One season ran into the next and she would stay — more or less — until the end of 1931. The Hayground decade formed an enormously productive period in her career. To make money she turned out local landscapes and neighbors’ portraits. On a mystical level it was a time of expanding awareness, of brushing on canvases inner reflections and states of consciousness that created abstractions such as “Being” (1926). These impulses were influenced by winter visits to kindred Modernists, particularly the Glass Hive community in South Pasadena, Calif.

There Pelton was drawn to Dane Rudhyar, a Parisian-born pianist and aspiring painter who became a special friend. She was older and established, while he valued her compliments; she felt “sheer delight in his presence,” and fantasized that “our friendship, already close, would bloom into love. For the first time in my life I could see myself marrying. . . .” However, as had been true of her mother and grandmother, there would be no happy marriage.

The relationship that she ultimately craved was with her natural surroundings. In Cathedral City, Calif., “the ring of mountains made me feel embraced,” she said in 1932, providing contentment for her last 30 years as well as the enduring “Desert Transcendentalist” designation.

One of Ms. Coates’s early retrospective chapters, effectively explaining Pelton as she was shutting down, and before the author tells Agnes’s story in chronological sequence, is headed “Inventory.” The date is Feb. 6, 1961, five weeks before Pelton’s death. While musing about her abstracts, she almost speaks to viewers who might have visited the Whitney exhibition: “I send blessings to those who received the messages conveyed in these pictures; especially those who absorbed the messages.”

Agnes Pelton died on March 13th, exactly 59 years before her show was to open. Surely there will come another in-person opportunity to absorb her messages — this time enriched by “The Pelton Papers.”

J. Kirkpatrick Flack’s “A Modernist in the Old Mill: Agnes Pelton at Hay Ground, 1921-1931,” appeared in the summer 2009 edition of The Bridge, the former journal of the Bridgehampton Museum, which can still be found online. A retired University of Maryland history professor, he lives part time in Water Mill.