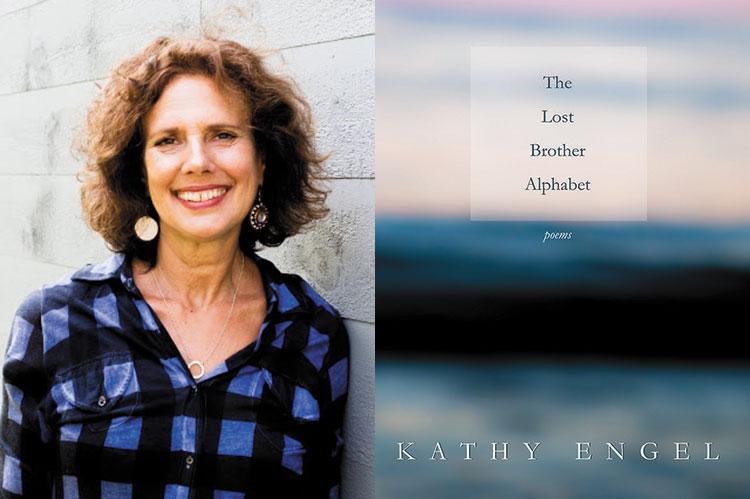

“The Lost Brother Alphabet”

Kathy Engel

Get Fresh Books, $16

Kathy Engel’s “The Lost Brother Alphabet” concerns itself with mortality or, more specifically, with the mystery of how we endure and what we become after those we love die. In Ms. Engel’s case, the loss of her father in his 80s and her brother’s suicide dominate her consciousness.

Ms. Engel never hides behind a persona; her loss and her grief are too personal, too powerful to obscure with a mask. She wants us to know that this is her experience, her existential struggle, which must somehow be overcome or transformed for her to live, and she lays bare her emotional response to it. The poems attempt to create meaning from loss, that quintessential human endeavor; they ask the questions that grief provokes.

An alphabet, of course, is a language’s rudimentary elements, and Ms. Engel creates in these poems a starting-point to make sense of a family’s deaths. She writes with the heart’s intellect, desperately attempting to process feelings that may, in fact, resist processing. The poems are edgy and angry and interrogatory, often concluding with questions beyond answering.

The book begins with “the body i write for,” a poem serving as a prologue and the only one in the collection whose title is rendered entirely in lowercase letters. It serves as a manifesto of sorts, wherein Ms. Engel resolves to struggle for authenticity and accuracy in the expression of her feelings, ending with the phrase “craving redemption.” My Webster’s defines redemption in part as “to extricate from or help to overcome something detrimental”; “the body i write for” announces an intention to discover and reveal powerful emotions — of anger, sadness, perplexity, and perhaps a touch of survivor’s guilt — and thereby arrive at “Gratitude,” the collection’s penultimate poem. But the use of lowercase letters in the title makes it seem that we’ve arrived, childlike, at the beginning of the evolution of discovering how to live when one’s loved ones die.

Most of these poems are written in free verse, with a few Tanka and haiku added. These shorter poems seem the weakest in the book because they do not surprise or provide moments of startling clarity. Another device the poet employs ineffectively is anaphora, where the repetition seems the result of some random workshop prompt.

But interspersed through the volume are poems that take for titles a letter of the alphabet. All these poems concern themselves with Ms. Engel’s brother and his suicide. These alphabet poems are wondering, accusatory, grief-stricken, and brief, as though the exercise of addressing her dead brother and sustaining the emotion of doing so would be untenable in a longer poem. Ms. Engel in these poems condenses her emotional energy, resulting in poems that bristle and flare. Each of these alphabet poems also utilizes a preponderance of words that begin with the title letter. Here’s “G” in its entirety:

Good

or not good

Hand at groin

on the couch after dinner

Grandiose, a

gazillion everythings

Grief is a body part

Gone, brother,

gone

But a gun

Here, Ms. Engel’s grief is palpable. It’s a body part, this poem harkening back to “the body i write for.” It gives in to the inexplicable; the last line appears to begin a new sentence that remains a fragment. The poem seems disjointed and mirrors the poet’s emotional state. In fact, all of these alphabet poems reveal a poet living on the edge of control. In “K,” Ms. Engel restrains her anger and allows it to merge with an accusatory question, creating powerful closure that may stun the reader:

Kiss what’s gone

Kiss the sad kidney

Kiss the pain

Don’t explain

Kiss kill killed yourself how could you

Here, the emotional upheaval is indicated by the odd juxtaposition of “Kiss kill killed” and the run-on sentence. Unlike Wordsworth, Ms. Engel understands that poetry is not always the result of powerful moments recollected in tranquillity, that tranquillity may not be preferable for such a project, dealing with the abrupt and unexpected loss of a brother who has taken his own life.

At the end of “R” Engel writes, “I’m not racing toward clarity / I ask for release / Remission.” The final word puts me in mind of cancer treatments and reminds me that these short alphabet poems that attempt to explain the unfathomable function therapeutically even if they do not result in satisfactory answers.

In contrast, many of the collection’s other poems deal with the death of Ms. Engel’s father. These poems tend to be longer and are imbued with a sadness that feels palpably rendered. If the poems about the brother feel tortured and torqued by pain, the poems about the father feel resigned.

My favorite of these may be “Staying in My Dead Dad’s Apartment.” Ms. Engel handles a visit with her dead father’s spirit seamlessly. The poem begins in pedestrian fashion; Ms. Engel has blown a fuse, disturbed the super, and broken a Chemex coffee pot. Just when readers might wonder where the poem is going, she writes, “I bumped into my dad in the narrow kitchen where he used to stand . . . / We had a cup / of coffee; he gave an odd disappearing smile then went back to death.” The poem’s longer lines slow it down, emphasizing the nonchalance with which Ms. Engel announces this visitation, shocking the reader the way in which good poetry is capable.

Another excellent poem is “My father,” placed near the book’s conclusion, where the poems seem to shift mood. The collection’s final four poems, of which this is the first, reveal a change in Ms. Engel’s perception of grief, a kind of acclimatization toward her subject matter. She indicates this first in “My father,” which begins as a typical memory poem, listing certain of her father’s quirks. In poor health, her father, who “gave up God,” asks, “what do you mean / when you say spiritual?” Ms. Engel, with her own characteristically powerful closure, answers, “Maybe it’s what we don’t know.” This concession to idiopathic spirituality opens a way for her to finally begin processing her grief because it admits to finding comfort in the unknown.

Other poems in this book include wisdom expressed by a teenage daughter, who tells Ms. Engel in “Advice” not to “be a tortured / poet: write about something else,” sound counsel for when a poet becomes obsessed with and overpowered by emotion and uneasiness. Ms. Engel also makes use of horses as a motif; memories of the poet’s interactions with horses and particularly the appearance of horses within her dreams all symbolize the strength and work needed to deal with devastating loss.

This book is a chronicle of working through one’s grief, which leads, by its conclusion, to gratitude for what’s here and now instead of continuing to grieve for what isn’t. It’s where, I suspect, all of us hope to arrive after the loss of loved ones. I look forward to Kathy Engel’s next book, in which I hope she’ll provide her readers with more “poems of love,” the processing of monumental grief behind her.

Dan Giancola’s collections of poems include “Songs From the Army of Working Stiffs” and “Part Mirth, Part Murder.” He teaches English at Suffolk Community College.

Kathy Engel is chairwoman and associate arts professor in the department of art and public policy at N.Y.U.’s Tisch School of the Arts. She lives in Sagaponack.