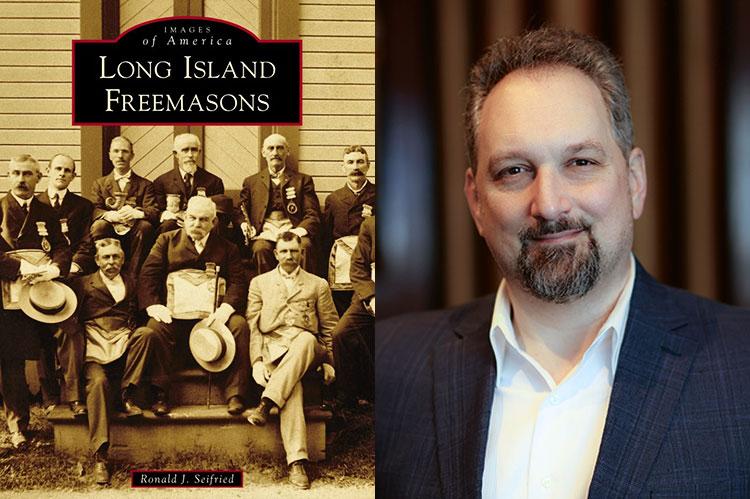

“Long Island Freemasons”

Ronald J. Seifried

Arcadia, $24.99

Let's pause a moment to reflect on the invaluable work of the Arcadia publishing concern. I'm talking about those slim paperback volumes, photo-heavy, under the Images of America banner. The seemingly endless array of titles can be almost comical in their specificity, as with "Movie Houses of Greater Newark." And yet you know there are some beauties in there.

In some cases, the books cover 20th-century territory that simply isn't being covered much elsewhere, or at all: "Black Artists in Oakland." Attention must be paid. Or, from Wisconsin, "Beloit's Club Pop House," its cover showing a bespectacled and mustachioed hep cat in sepia tones, head held high as he plucks a stand-up base. Tell me more.

This is an America that's vanished, and particularly for fans of a bygone urban lifestyle, heartsickness can result. "Slabtown Streetcars." That refers to a section of Portland, Ore., and, as in every other city where jaunty trolleys once coursed the streets, it goes without saying they should still be running.

Full disclosure, I happen to be married to an author of one of these titles, "Bridgehampton's Summer Colony," so I'm always on the lookout for that "local connection." Like Ronald Seifried's recent "Long Island Freemasons," which starts out on the East End, or, as chapter one has it, "Where the Sun First Shines on New York," and where the practice was introduced by none other than Brother George Washington on a five-day tour of the Island in 1790.

By 1804, the Island's fourth Freemasons lodge was established in Sag Harbor, but like the village itself, with its long history of destructive fires and renewal, the lodge had its fits and starts, first meeting in the Division and Union Street attic of one Moses Clark, and then on to the third story of the Nassau House on Main Street, destroyed by fire, onward into the building that replaced it, Hotel Bay View, where the People's United Bank parking lot is now, to the Presbyterian Church that preceded the Old Whalers Church and that subsequently was moved and renamed the Atheneum, "a 500-seat community lecture hall and theater," Mr. Seifried writes, with "dances, basketball games, stage plays, a basement bowling alley, and Sag Harbor's first movie theater. . . ."

Also destroyed by fire.

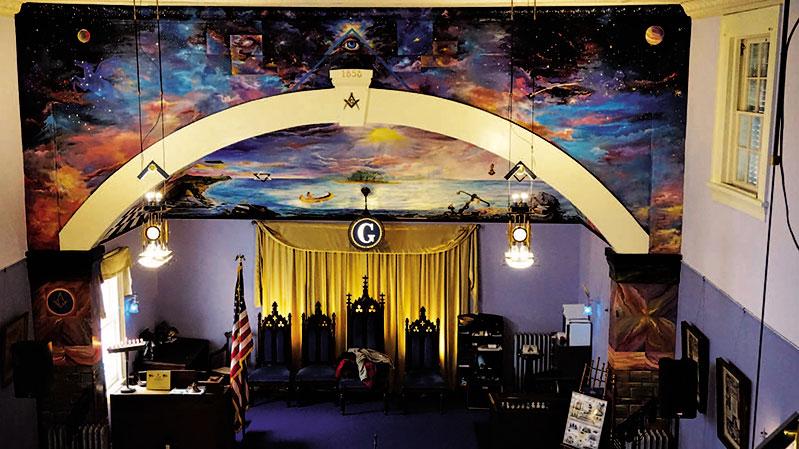

The Wamponamon Lodge, as it came to be known, apparently an American Indian term for "into the east," moved in 1920 into the former mansion of the grande dame of Sag Harbor philanthropy, Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage. The Whaling Museum, that is, built in 1845, where the lodge remains today on the second floor.

Mr. Seifried, a member of the fraternal organization in good standing for 17 years, calls Freemasonry "a system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols," originating with the stonemason guilds of the Middle Ages, when the great cathedrals of Europe were built. Interestingly, the "society with secrets, but not a secretive society," forbids the "discussion of politics or religion in the lodge, creating an atmosphere of harmony. . . ."

Among the organization's many luminaries, Theodore Roosevelt spoke in 1902 about what attracted him to it, referring to Washington himself and how the lodge was "the one place in the United States where he stood below or above his fellows according to their official position in the lodge." On his merits, in other words.

"In the late 18th century, most brothers were farmers or seamen," preoccupying jobs that delayed the growth of the fraternity. Between the Civil War and 1900, the number of lodges on Long Island grew from six to 13, and in the post-World War II years, membership "exploded" in the "birthplace of the modern suburb." In Nassau and Suffolk Counties today, 28 lodges still meet, the author writes.

The book offers a quick captions-only tracing of Freemasonry in East Hampton, at first well entwined with the Sag Harbor lodge and experiencing its own peripatetic journey, from Newtown Lane to the second floor of what later came to be the V.F.W. downtown, where the Star of the East Lodge resided until 1978, when, yes, a fire broke out. It now meets in Amagansett's Scoville Hall.

There are choice tidbits throughout, for example the "ride and tie" system of travel back in the early days of Freemasonry on Long Island, in which to cover the many miles to a meeting "two brothers would start out, with one on horseback and the other on foot." The first would stop, tie his horse to a tree, and continue on foot, while the second got on that horse and rode on. And repeat, thus adding a measure of rest to the trip.

Those same groaning distances were on Franklin Delano Roosevelt's mind in 1931 when, two hours late for his speech, he paid a visit to the Jephtha Lodge in Huntington. "Longer Island," it should be called, he said.