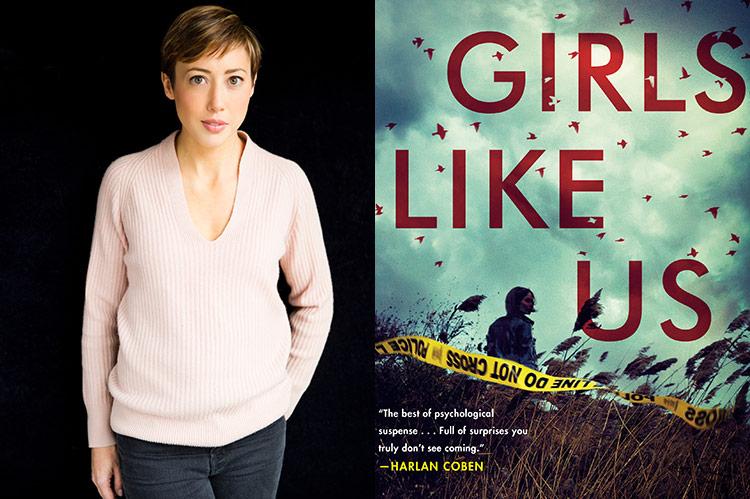

“Girls Like Us”

Cristina Alger

G.P. Putnam’s Sons, $26

By all accounts, the convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein never had property or a presence on the East End. Yet it isn’t difficult to imagine his well-funded loathsome behavior, involving underage girls and powerful older men, similarly enabled by willful ignorance and sanctioned by a corrupted justice system in any place where such conditions exist.

Suffolk County has had problems with police and prosecutorial corruption and an uber-rich and spoiled population heavily weighted on the South Fork. Many of the people in Epstein’s extended social orbit who make their summer homes here have their other residences in places where he lived, such as Manhattan and Palm Beach. With such crosscurrents, setting a comparable fictional story here is hardly unthinkable.

Cristina Alger has done just that, and her most recent book, “Girls Like Us,” gains gravitas and resonance that similar “ripped from the headlines” crime page-turners typically lack. A good winter vacation beach book for those who missed its publication this summer, it gains points for not insulting the intelligence of its readers (although some online reviewers sniffed at the ending).

Most books in this genre are forgotten the moment the last page is turned. This one lingers.

There are several victims in this book, but the “girls” of the title are two recent murder victims, each Latina and underage or close to it. The most recent victim has just been found mere yards from the house of James Meachem, a financier who just happens to have his own island in the Caribbean called Little St. James, the same as Epstein’s infamous hideaway.

Nell Flynn, the protagonist, whose mother was the child of Mexican immigrants, finds herself personally drawn to the girls’ cases and backgrounds when she returns home to Hampton Bays after the death of her father, Martin, in a motorcycle accident. An F.B.I. agent, she is recovering from bullet and psychic wounds from a recent encounter with a Russian mobster.

She went home to memorialize her father and keep a low profile, but soon her old classmate Lee Davis brings her in to consult on the murders. At the same time, she begins to wonder about what role her father, who was a Suffolk County police detective at the time of his death, may have played in the murders as well as the death of her mother, who was stabbed when Nell was young. Lee was her father’s partner at the time of his death, which further complicates things.

Nell stays at the shack that her paternal grandfather built and she grew up in at the end of Dune Road, to the east of the Ponquogue Bridge. It’s the kind of beach house many devised at midcentury and still in evidence here and there. These were either built from scratch or repurposed from disused buildings — an old post office, train station, or even a chicken coop — and dragged to the beach to serve as a small cottage.

Her father, with whom she had a tense relationship, and who was always an enigma to her, reveals even more puzzling behavior in death, leaving her a sizable bank account in an offshore location and an apartment in Riverhead with a mysterious tenant.

Nell finds herself at the center of the attempts by the local constabulary to figure out who done it after they rebuff her offers to bring in the feds. A convenient suspect gets all the attention, but Nell’s criminal sixth sense says otherwise. Soon she is inserting herself in a world of pimps and escorts and the rough-and-tumble area of certain villages and hamlets of the Town of Islip that are part of the county’s third precinct, a place where her mother’s parents settled after they came here illegally from Mexico. Her description of their lives here rings true:

“My grandfather owned a small farm back in Mexico. He found work as a landscaper. My grandmother cleaned rooms in a retirement home. They lived in a trailer with one other family. As rough as the third precinct was for them, it was better than Juarez.”

Ms. Alger, who has a house in Quogue, includes a good deal of social commentary in this book. Bubbling beneath the surface are questions of how much time and energy are given to victims who lack agency or prominence in the community, or how quickly do the moneyed classes close ranks when it serves their interest.

She also draws a line between the areas west and east of what she calls “the Cut,” i.e., the inlet in the barrier beach between Hampton Bays and Southampton Village created by the 1938 Hurricane. (Most people would refer instead to the man-made Shinnecock Canal farther inland as the main dividing line between the South Fork and the rest of Long Island.)

On the Southampton side, the cars are expensive, the privet is high, and the private school girls are still playing tennis in late September. Their careless behavior carries little consequence. Just down the street from where those girls almost cause an accident on Meadow Lane, Nell and Lee examine the second murder victim.

It’s worth noting that a good deal of the locales and streetscapes Ms. Alger describes are familiar, but some are just enough off the mark to be puzzling. She writes that the county park at the western end of Meadow Lane is where locals park their trucks on the beach and fish, when it is a village beach to the east of that park where that happens. And there are other little things (“the” Montauk Highway) that are distracting for someone who knows the area well. It’s barely worth mentioning the overgeneralization of the police forces on the East End, but to those who understand or care about the difference between state, county, town, and village cops, it might also be a distraction.

A number of online reviewers found the ending predictable. In the sense that the number of characters is limited and one of them has to be the main bad guy, sure, that’s true. Yet there are plenty of surprises and some unexpected twists to push you to the finish, and lots of tension along the way. The women whose lives were lost in the novel feel real — specific in their characterizations, yet universal as (like us) they try to make the best of their circumstances.