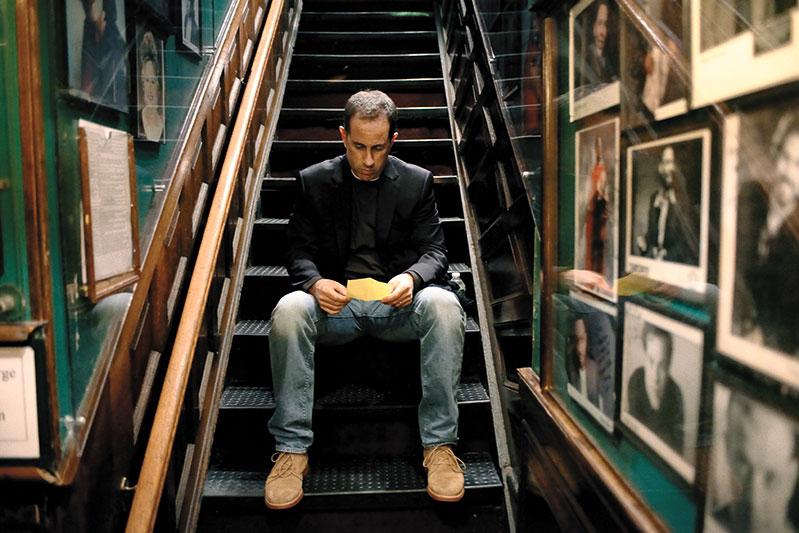

“Is This Anything?”

Jerry Seinfeld

Simon & Schuster, $35

"Is this anything?" is what one stand-up comic asks another about a new bit or joke he's thought up — meaning is this funny, worth working on to incorporate into my act? Jerry Seinfeld's book is a transcription of notebooks he's kept for the past 40 years, in which he jotted down his ideas for the gags that made up his act, and I promise you, most of these entries — ranging in length from a few lines to a few pages — are very funny; I don't remember the last time I laughed out loud while I was reading a book, and even without Jerry's distinctive deadpan delivery, the material speaks for itself.

I admit I'm biased in Jerry's favor, a huge fan not only of the iconic show that bore his name but of his stand-up as well, a snippet of which, you'll remember, began and ended each episode of "Seinfeld." And stand-up is pretty much all he's been doing since the show ended 20 years ago (except for "Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee"). I'd love to have had Seinfeld's life and career, standing in front of a microphone, looking out at a sea of upturned, expectant faces waiting to laugh. For most people, public speaking is a nightmare; to Seinfeld (and to me), it's a dream come true.

But I knew I could never sustain the career of a professional comic, so I did the next best thing, I became a college professor, which actually resembles but has some advantages over doing comedy: My audiences didn't walk out or heckle me if they didn't like my act. And one girl in my Shakespeare course at N.Y.U. came up to me after a lecture and asked me if I'd ever done stand-up, the nicest compliment I'd ever gotten.

Because it's organized chronologically over the past five decades, "Is This Anything?" is both a history of American habits and preoccupations and also an autobiographical record of the thoughts of an analytically minded American male as he progressed from his 20s to his 60s. Like his show, his comedy isn't political or tendentious or edifying; it's made up of the minutiae of ordinary life — out of subjects like whether Superman's boots fit into Clark Kent's street shoes, or why a cereal is called Grape-Nuts when it contains neither grapes nor nuts, or why women need so many cotton balls when men don't need any.

The strangeness of female behavior, which has been a staple of male comedy since Aristophanes, is one of Jerry's favorite topics. "I know I will never be able to understand how a woman can take boiling hot wax, pour it on her upper thighs, rip the hair out by the root, and still be afraid of a spider."

He didn't love doing "Seinfeld," he tells us in one of his brief chapter introductions; it didn't give him time to develop his monologues. But he adds that Larry David, the producer and co-creator, in some ways approached the show as if it were stand-up, in the rhythm of the dialogue and the mind-set of the storylines. And there were storylines, despite the oft-repeated legend that Jerry pitched the show to TV executives as being about "nothing." It's about the daily life of four self-absorbed, unlovable people, and the prime directive given to the writers, it's said, was "No hugging, no learning."

His career took off in the early '80s, when he appeared on Johnny Carson and, as they say in the business, killed. I don't know which routines he performed that night; probably not the ones about what we do in the bathroom, which are among the funniest, but there are plenty of other things tumbling around in his fertile mind.

He's bemused by the fact that Neil Armstrong's toothbrush is on display in the Smithsonian, in a glass case, with a sign that says "On loan from Neil Armstrong." On loan? "Neil — give them the brush," thinks Jerry, unless you come back every night to use it. Old people driving in Florida leave the directional indicator on all day, which signifies, says Jerry, a turn that is legal if you're over 80 in that state, called the Eventual Left. And there are throwaways, like, "Men are not interested in what's on TV. Men are only interested in what else is on TV," which is absolutely true.

Jerry's life is just like our lives; that's why he's so easy to connect with. Like him, I can never find my car in a parking garage; I battle strangers for the armrest on airplanes and in the movies; I filled out the ID card that came with my first wallet when I was 10. No matter how much we may love shopping for clothes, don't we all hate "shopping bags . . . receipts . . . tags, pins, labels, hangers, buttons, zippers, drawstrings, lapels"? "I hate fabric softeners and static cling," he says, "so I lose either way." And I agree with him that cars are an improvement over horses. "I get out of a car that has 500 horsepower. So I can sit on an animal that has 1," notes Jerry, who loves and collects automobiles.

I think, though Jerry never mentions him, that George Carlin was his comic muse (with Kafka pulling their strings); they're fascinated by the absurdities that the rest of us take for granted, especially ordinary language. A decade ahead of his time, Jerry was riffing on bogus job titles in the '90s, people saying things like, "Right now, I'm managing regional development systems. Doing research, production, overseeing and administrating, assistant to the supervisor."

The language of merchandising is one of his favorite targets: "No one wants any amount less than 'EXTRA-STRENGTH.' . . . You can't even get 'STRENGTH.' . . . Some people are not satisfied with 'EXTRA.' They want 'MAXIMUM.' . . . 'Give me the MAXIMUM ALLOWABLE HUMAN DOSAGE. Figure out what will kill me and then back off a little.' "

When I ran into Seinfeld in the Amagansett Square parking lot last summer, he and his family were preparing to drive an ancient Volkswagen van, with four bald tires and rust eating the fenders, to California. What a dumb but inspired idea! It made me want to go with them. We need Seinfeld to inspire us like that. In some ways he's like a child, or one of Shakespeare's fools, the innocent observer who points out what the rest of us have missed, that the emperor has no clothes on.

You don't have to sit down and read this book from cover to cover; just dip into it when sheltering in place is getting you down. For a few minutes, at least, you'll forget your obsession with Covid and the election mess.

Richard Horwich taught English at Brooklyn College and New York University. He lives in East Hampton.

Jerry Seinfeld lives in East Hampton and New York City.