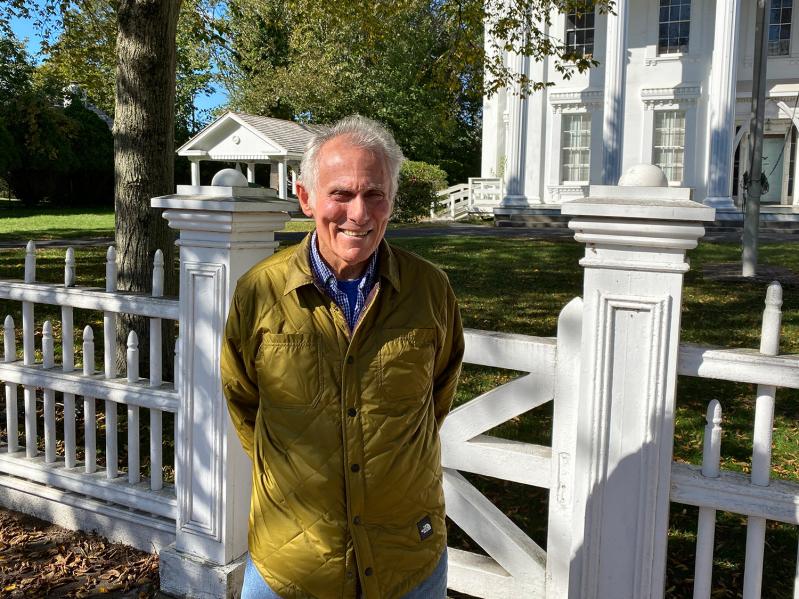

Rudolph Serra was still in his twenties, only a couple of years removed from earning his M.F.A. from the University of California, Berkeley, when his work was selected for the 1975 Whitney Biennial. "The kind of work I was doing in the Biennial was about figuring out a physical problem to build and then building it," he said recently, noting that he studied architecture in high school.

It takes only a few minutes with Mr. Serra to understand that just because his work had been validated by a major museum didn't mean he would settle into that as his signature style. While at Berkeley, he studied with Peter Voulkos, whom he calls "the Jackson Pollock of ceramics."

"I found fluidity in the expressionistic character of what I saw Peter do with material more interesting. What interested me is that he was running more of a risk making these things out of ceramic, and if he threw the pot and it fell, he might decide it was better than his idea and go with it."

"So in leaving the genre of part-to-whole construction, I got to working with material that was always more fluid," including plaster, Hydrocal, asphalt, even sweeping compound. He made a series of works in plaster that were essentially molds, but without the thing the mold was made for, so they were hollow and smooth on the inside, rough on the outside. "I felt, the more tension I could make between the inside and the outside, the better."

Mr. Serra eventually settled on clay, and worked with it for many years. "Clay offered me a material that was fluid, that I could plop, and fold, and do this and do that, that could draw different ways that seemed to be freer." As he explored and revealed the possibilities of the material, he achieved seemingly endless variations with it.

Then came the pandemic, and he could no longer get clay. Because it was the fluidity that he liked, rather than the material itself, he sought another route to what have been called his three-dimensional drawings. He found it with surfboard foam, which he finishes with aqua resin, a water-based fiberglass.

When working with resin or fiberglass, he remarked, "you're knocking on the door of cancer -- but with aqua resin there are no fumes, no dust, you don't have to wear gloves." (Aqua resin was developed by a sculptor who lives on the top floor of Mr. Serra's Greene Street loft building.)

While ceramics allowed him to draw in space, his recent work begins with shaping the surfboard foam before applying the finish. "This is, in a way, going back to Arp, to Brancusi, to Moore," he said, "but it's not biomorphic, it's not figurative. It's gestural, but it's carving. There aren't a lot of people carving anymore, that's out to lunch."

"Curling, Swirling Contours in Space" was the title of Mr. Serra's July show at Sag Harbor's Mark Borghi Gallery. That exhibition featured pure white three-dimensional sculptural forms as well as gestural drawings on paper, all made since 2020.

Mr. Serra calls the recent work "asemic" writing, or writing that has no specific content. He likens it to Arabic writing he saw in Spain that he found beautiful, even though he didn't know what it said. "When you're looking at it, asemic writing lets you get lost in your imagination, and I hope you have a nice journey there," he told Julia Szabo during an interview for The Purist magazine.

Mr. Serra grew up in San Francisco, "straight middle class, in the avenues near the ocean. I fished there with my father, and later my older brother gave me a surfboard, and I'm still surfing today." The sculptor Mark di Suvero lived two doors away.

"Before I was born, my father and Mark's father worked in a shipyard. I think that influenced Mark's and my brother Richard's work." His father built a lot of the furniture in the family house, not as a career but as a side note. "The lasting memories I still have of him are that he was focused, he was content, he was self-assured, he was proud."

Mr. Serra also spoke of his mother's influence. While not formally educated, she read Tolstoy and Dostoevsky at home, and took him to Stanford, to Berkeley, and to "every museum in the city" when he was a child. "I feel comfortable in the art world and in museums because that's where I was at age 4, 6, or 10. My parents never taught us to chase money."

Even though he has lived and worked on the East Coast for decades, Mr. Serra still feels like a Californian. He visits regularly. "When I came east for a teaching job in Storrs, Conn., everyone said, 'Isn't it great here, we're in the woods.' I thought, let me out of here, this is claustrophobic. The sense of California, of being able to see for miles -- the farther I can throw a stone, the more assertion I feel I have in the world."

After graduating from San Francisco State University with a B.A., his life changed completely. At Berkeley, "there were people from other states, other countries. And the teachers were artists, real artists." Among them were Voulkos and Jim Melchert.

Mr. Serra spoke about the impact on his work of a book called "Patterns That Connect: Social Symbolism in Ancient & Tribal Art," which draws connections between patterns and images across ancient cultures throughout the world. "I thought maybe some things have meanings that are deeper than" passing fashions.

Subsequently, in a village in Africa, he saw small totemic structures meant to keep evil spirits away during the night. "I thought, this need to make a symbol and put it into the world is more primary than the flavor of the month" -- his shorthand phrase for transitory trends in art and culture.

"Those stumps had power in them. Some things hold more weight, we hold them longer, they're dearer to us, at least to me. I'm trying to go there somehow. I told an interviewer that we as artists choose to take the power to put something into the world. I'm choosing to put beauty there."

Mr. Serra and his longtime partner, the artist Margia Kramer, divide their time between his SoHo loft and her house in Sag Harbor, which she bought in 2001. "I think I work harder in the city because the city is abrasive," he said. "It makes me burrow in and say, I've got to shut the door and get to work. Here, it might be nicer to go watch the sunset at Long Beach."