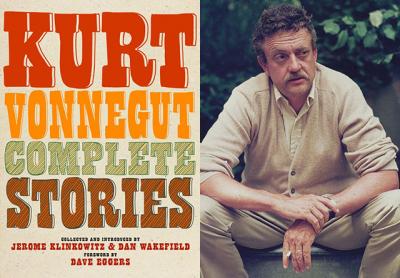

Vonnegut's 'Complete Stories'

“Kurt Vonnegut:

Complete Stories”

Collected and introduced by Jerome Klinkowitz and Dan Wakefield

Seven Stories Press, $45

Once upon a time Kurt Vonnegut walked the Hamptons. The last time I talked to him was outside the Sagaponack General Store. I was walking to my bike with my lunch; Kurt was slogging north toward the store. Kurt didn’t really walk; he slogged as if the weight of the cosmos were on his shoulders.

“Hi, Kurt,” I said.

“Hi, Bill,” he said, and slogged on.

The very first time I talked to him I was a drunk college kid enamored of “Player Piano,” his brilliant 1952 novel that predicted with horrifying accuracy the robotic future that is upon us. Thinking I’d never connect, I asked information for his phone number in West Barnstable, Mass. Amazingly it wasn’t unlisted. I dialed. Kurt answered. Good grief! What’s a buzzed college kid to do when a god answers?

“What are you doing now?” I blurted out.

“I’m playing poker with a friend,” Kurt said.

“Oh!” said I, and hung up in terror.

In between the first and last conversations, we met now and then at various Hamptons cocktail parties. At one I announced to him my literary disdain for “The Bridges of Madison County,” a purple-prose best seller of the time, expecting he’d agree. “Well, I tell you, Bill, that novel meant a lot to many women.” Kurt shut me up.

Kurt was a contrarian, and we need one badly out here on the East End. When men landed on the moon I was awash in tears at the triumph of the human spirit. Kurt pooh-poohed the entire adventure in The New York Times Magazine. “Moon!” he scoffed. “Big deal.”

When the most recent extravagant beachfront mansion was planned for Sagaponack — one with dozens of toilets — Kurt was horrified. In fact he vowed to leave the Hamptons forever if it ever went up.

It did.

He stayed long enough for me to say hi at the Sagaponack store that last time.

Boy, do we miss him — that shambling, head down, creased-face man in the beat-up raincoat who loved the world, and was broken by the foolish people who were trampling it underfoot, helpless to help themselves.

So what about this book? Is it any good? Answer: Not only is this book good, it is monumental — 912 pages of Vonnegut’s stories both published and unpublished, 98 stories total. If you love Vonnegut, you need this book.

A special thanks to Seven Stories Press, a small independent publisher that obviously put all its love and finances toward collecting and printing this handsomely designed and bound volume. One does not venture into a project this huge without lots of moxie and affection. No e-book this, it’s meant for the long run after our electronic mania has subsided.

In his foreword, Dave Eggers (novelist and founder of McSweeney’s) states, “This collection pulses with relevance . . . the satisfaction we draw from seeing some moral clarity, some linear order brought to a knotted world, is impossible to overstate.”

The stories were culled and are introduced by Dan Wakefield (novelist and author of the memoir “Returning: A Spiritual Journey”) and Jerome Klinkowitz (author and scholar of midcentury American literature). The stories are divided into thematic sections: “War,” “Women,” “Science,” “Romance,” “Work Ethic vs. Fame and Fortune,” “Behavior,” “The Band Director,” and “Futuristic” — each section introduced by Mr. Wakefield or Mr. Klinkowitz.

Along the way the editors relate the path of Vonnegut’s life — which might be a revelation to his multitude of fans who remember him as a countercultural icon.

Vonnegut in fact was for 20 years a writer of short stories about middle-class America that he sold to popular slicks like Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post. He was a determined craftsman, shaping his tales to the pleasure of his editors and enduring stacks of rejection slips with stoicism.

He was born in Indianapolis in 1922, played the clarinet in the local high school band, studied at Cornell (biochemistry), was a soldier in World War II captured by the Germans in the Battle of the Bulge, survived the firebombing of Dresden in 1945 (the setting for his first commercially successful novel, “Slaughterhouse-Five”), and labored as a publicist for General Electric from 1947 to 1951, hating the corporate life, composing short stories at night.

When his stories started to sell to the slicks (at 50 cents a word), he was able to quit G.E. and settle in West Barnstable with his first wife, Jane Cox (the true unsung hero here — his cheerleader, file keeper, and mother to their three children plus three more adopted when Kurt’s sister and her husband died). Somehow, with the odd jobs and a stint at the Iowa Writers Workshop, Vonnegut supported his family as a freelancer (almost impossible today) with his short stories and early novels like “Cat’s Cradle,” “Player Piano,” “Mother Night,” and “The Sirens of Titan,” which sold poorly until in 1969 “Slaughterhouse-Five” made Vonnegut a celebrity flush with cash, a situation that made him wary: “I feel uneasy about prosperity.”

He was always on the side of the underdog, and I suppose he felt out of place in the glittering Hamptons late in his life (he died in 2007).

When I saw him for the last time, his heavy-lidded eyes gave the impression of “unalterable weariness for the crimes of his fellow humans,” as Dave Eggers sums him up in his introduction to this wonderful labor of love.

Bill Henderson edits the Pushcart Prize and lives in Springs. His memoir “All My Dogs” is just out in paperback.