Not Your Elegant Oysters: John Alexander at Guild Hall

“You don’t speak like you’re from around here,” said John Alexander last month, detecting a sense of otherness in a visitor’s neutral, slightly Philadelphia-inflected accent. It was a funny comment from a guy whose Texas drawl doesn’t sound like it has altered much since his own journey east several decades ago.

His blunt observations, lacking apparent irony, are disarming because they are far more direct than most people are willing to be and humorous, prompting some of his oldest friends to call him one of the funniest people they know.

At the time of this observation, Mr. Alexander was in the final stages of installing his show at Guild Hall, which is up until July 28. He will speak about it at the museum on Saturday at 4 p.m.

The exhibition is a snapshot of what has occupied the self-effacing artist most recently. Almost all of the paintings were completed in 2012 and 2013, some practically drying on the walls. This was more a function of his reluctance to let some paintings alone once they are completed than a lack of discipline for deadlines.

“I’m not a particularly facile artist,” he observed. “I struggle through a lot of it and when to keep going or to stop.” His compositions are primarily representational with surrealist elements or themes, but he said he works like an Abstract Expressionist, particularly Willem de Kooning, adding and then reducing the marks he puts on the canvas. “Some painters work across the canvas, section by section, and when they get to that last corner, they’re finished. I’ve never been able to work that way.”

Although Mr. Alexander may be best known for the politically charged figural paintings executed early in his career and at various times since, his current preoccupation is the natural environment, both as a touchstone to childhood memories as well as a more pointed examination of the effects of global warming.

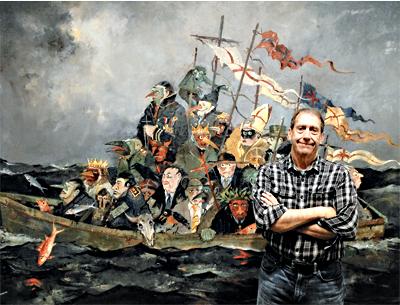

He has not entirely abandoned the figure. His “Lost Souls” depicts a choppy sea and a dinghy crowded with animals and people who look like historical and mythical bad guys. Many are wearing Venetian-style bird masks, which make them look more menacing, creating parallels between them and the other paintings that feature birds and fish.

There is a crude and primitive quality to this work that undermines the skill with which it is painted. “Technique is important to me. I spend a lot of time on it.” Mr. Alexander has a number of champions in the academic and institutional worlds and a fair number of voluble detractors, but everyone seems to agree that the man knows how to paint.

The exotic birds he paints are real, “ones you see in the Texas Gulf Coast and in Florida. They’re originally from South America, but they have been making their way northward.” Their northern appearance does raise the issue of global warming, said the artist, just as other species never or rarely seen here are becoming more common. “I don’t carry signs, but I am very concerned emotionally about the environment.”

Here, the birds’ eyes, which in reality are on the side of their heads, are looking up and out at the viewer. “And that’s purposeful,” said Mr. Alexander. “I’m very conscious of them having a psychological experience with the viewer. You’re looking at them and they’re looking at you.”

The birds exist in shallow space, as do most of the subjects and objects in his recent compositions. “I want them to be in your face. In the early days in the 1970s, I did nothing but deep-space paintings. These are not that, and it puts them in a much more psychological confrontation.”

The earlier works came from a childhood spent looking out the window at the vast open Texas landscapes of Beaumont, where he was born, and the rest of the state’s southeastern region. “You’re detached. The landscape is out there, but you’re not.” He noted that it can be 250 miles between cities; growing up, he became accustomed to spending enormous amounts of time in cars. The road trips he took when he was at Southern Methodist University could be five hours long, he said, just to spend a weekend in New Orleans. “It would be like driving from Syracuse to New York City for the night. People in the Northeast just don’t drive they way they do in Texas.”

Mr. Alexander has a unique way of dealing with traditional still life subjects, such as fruit or oysters, as well. They are not the subdued memento mori of history, laid out elegantly on a table. His oysters are jammed into the painting in an allover flat composition that manages to be about formalism even though its subject matter is recognizable. It came from an encounter with a photograph in New Orleans, where the artist guest-teaches and spends a good deal of time. At night from a gallery window, the photo looked like the subject was oysters, but up close and in the light of day it turned out to be an abstraction of something quite different. “I thought what a great idea it was to paint oysters the way I thought I had seen them,” and so he did.

The watermelons, another allover composition of smashed and mutilated fruit still on the vine, are quite another thing. They are a link to his childhood and the flora and fauna he grew up with, but there is something else there too. “There are two reactions to that painting,” he said. “People find it beautiful or menacing, and for me that is successful. It’s what I’m trying to do as an artist, if that comes across.” Since his early days, he said, a sense of impending doom has been attached to all his paintings. “It’s aimed at the natural environment.”

Just as powerful, however, is that other distant attachment and meaning, one that has become more compelling as he grows older. “You go to the grocery store today and you buy a bunch of watermelons and hack them up, but your heart and soul is in that other time, in the sandy, east Texas soil. It never leaves you.”

It’s a feeling that people either understand and embrace or viscerally react against. “I see people at my exhibitions and some walk in and out, but others stand there and stare forever.” His detractors, he said, often make their complaints about him personal. “Also, it’s hard to classify me. Where or what category would you put that picture of watermelons?”

For Mr. Alexander, painting can sometimes be “just like jazz. You’re making noise, then it becomes coordinated and structurally sound. You get those instruments working together and it means something. I like when painting brings a lot of things together that way.”

His work is emotionally provocative, and that is a conscious decision, “but only to my own feelings.” When people view his canvases he would like them to think about the world around them and about painting itself. “There’s nothing pretentious about it, or me,” he said. “I’m filled with insecurity. And if you think you’re great then you just start repeating yourself. You need a little fear.”