More Emerges About the Freeman Ned

It is a simple entry in the 1780 town trustee records: “Ned negro to ring the bel for 30/,” and yet it says so much.

Until recently, all that was known today about Ned was that he was a free black man whose grave marker was in a backyard off Morris Park Lane in East Hampton. Last year, through the efforts of quite a number of people, it became clear that he had been buried near his own home on land either sold or given to him by a member of the Osborn family, to whom he may have been either an indentured servant or a slave previous to gaining his freedom.

Ned’s story, now that it is beginning to come to light, is important because it adds a fresh dimension of understanding about East Hampton around the time of the American Revolution and about the country as a whole. In him we recognize that the communities that would become the new United States were a lot more complicated than the almost all-white versions of history we might have learned in grade school.

Hugh King had phoned me on Monday to say that Rosanne Barons had found Ned in the East Hampton Trustee records 28 times between 1780 and 1816, hired annually for varying sums to ring the town church bell.

Several weeks ago, after an article I had written about Ned and the search to learn who he was appeared in The Star, Ms. Barons, looking through the trustee records for something else, noticed his name.

He appears in the 1784 record as “Jeremiah Osborn’s Ned” agreeing to ring the bell for one year for 24 shillings and so on in the ensuing years’ records. In a church membership roster for 1799 that Ms. Barons directed me to on Tuesday, he is listed as a “freeman.”

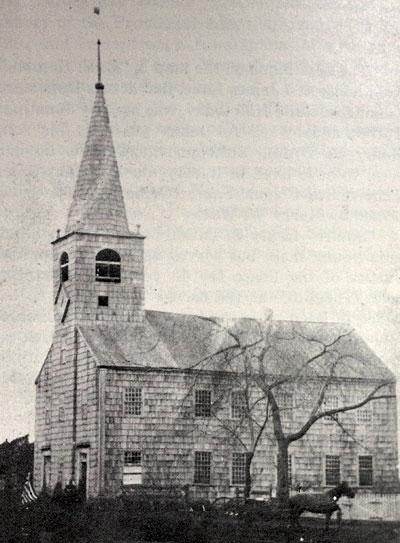

The church where Ned rang the bell for as many as 36 years stood directly across Main Street from where the Star office is today. The site now contains Guild Hall’s nondescript north wing. It was a tall, shingled building, with two doors facing the street and at least two dozen 30-light pane windows. A square bell tower rose above its broad, sloped roof, and above that was a six-sided steeple topped by a mast and, finally, a weathervane.

More than one might assume still remains of the 1717 church. The clock face, a black and white-painted wooden square about six feet across, is in the East Hampton Historical Society collection and was exhibited last year. The weathervane is preserved at Clinton Academy.

April 8, 1816, is the last time that Ned’s name appears in the copy of the trustee records we keep at The Star. On that day, he again agreed to ring the bell for one year, and, by then, was to be paid in dollars — four. The names of the people hired to tend the bell in the years following his death in 1817 are not recorded.