Long Island Books: No There There

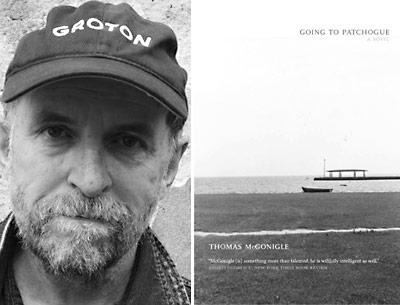

Thomas McGonigle’s “Going to Patchogue” is a slight, basically plotless metafictional novel of loss, identity, and discovery. First published by the Dalkey Archive Press in 1992 and out of print for a number of years, it has recently been reissued in a paperback edition. The Dalkey Archive is a small publisher known for its interest in less traditional literary works.

“Going to Patchogue” is more unconventional in terms of style than subject matter. The novel is first and foremost a meditative and reflective story about how one’s sense of self is determined by one’s relationship with and understanding of the past and the place one grew up. The novel shares some characteristics with the tradition of the road novel, even if the road here is no more than the 60 miles of Long Island Rail Road between Manhattan and Patchogue and may be more metaphorical than actual. The book is what Kerouac termed a “true-story novel,” and Mr. McGonigle’s sustained use of stream of consciousness, free association, unpredictability, and spontaneity to tell his story seems to embrace Kerouac’s advice that the writer “sketch the flow that already exists intact in mind.”

Stylistically, he stretches the narrative boundaries by including a few dull photographs, a railroad schedule, newspaper clippings, and a play segment, although none of these items particularly benefit the story.

The protagonist, age 40, depressed and disheartened, and also named Tom McGonigle, decides to return to his hometown of Patchogue in the hopes of discovering or rediscovering who he is. He is motivated, in part, by his memory of Melinda, his distant and unrequited love from Patchogue High School. Whether Tom actually returns to Patchogue is not completely clear and not necessarily important because his trip is less geographical than it is emotional and intellectual. As he proclaims, “I don’t have to travel to Patchogue to be there. I am always in Patchogue.” His descriptions may be literal but the viewpoint is shaped wholly by his imagination, “avoiding the sterility of facts.”

“Going to Patchogue”

Thomas McGonigle

Dalkey Archive, $15.95

Tom attempts to work through his extensive list of longings, memories, disappointments, and missed opportunities as he tries to come to some understanding of who and what he is by way of where he has been. How is his identity — his sense of who he is (or is not) — connected to his life experiences growing up in Patchogue? Can he move beyond them to arrive at, if certainly not paradise, at least some better place? He speaks (endlessly) of going back to Patchogue as well as traveling to Bulgaria, Istanbul, Venice, and Dublin. He is in a constant state of traveling somewhere but never arriving, always caught in between and short of a destination he cannot ever satisfactorily identify.

As he looks back and reflects on his years in Patchogue, the people, places, and events become him. He tries to understand himself by understanding them, by “marking out the territory to be explored.” That territory comprises both inner and outer landscapes, and the autobiographical identity is constructed (if at all) in relation to the actual or imaginary people and places he remembers or encounters.

Although the novel is not so much about Patchogue as it is about Tom McGonigle and his idea of Patchogue, the local chamber of commerce will be in no hurry to endorse its errant son and the portrait of the village he presents. As Tom remembers it, the “old home town” is racist, insular, ugly, small-minded, and welfare-ridden. The people live marginalized lives within strict social and racial hierarchies. Patchogue is best defined by its excessive number of parking spaces. The depiction is an amalgamation of the subjective mind and actual fact. But if what he says is true about Patchogue, that it is a place “where nothing is forgiven, learned, or remembered,” then is it also true about him who seeks to define and understand himself by his experiences there?

Mr. McGonigle directly alludes to a number of writers, including Dante (Melinda is his Beatrice, Patchogue his hell), Thomas Wolfe, Thoreau, and Celine. He evokes Melville’s “Moby-Dick” at the beginning by merging and paraphrasing the brief introductory passages of Melville’s “Etymology” and “Extracts.” He offers up an accumulation of purported facts about Patchogue to establish the verity of the village to serve as his book’s ballast as Melville defines and affirms the whale to serve as his. The factual provides the foundation for the philosophic. Ahab has his whale, and Tom has his excessive pursuit of himself.

“Going to Patchogue” contains passages of intelligence, humor, and insight. These individual pieces, however, do not coalesce into a sustained and successful narrative. One can admire much of what Mr. McGonigle is attempting to do here without necessarily recommending the whole. Tom’s tiresome journey ends in a greater sense of despair, emptiness, and persistent unawareness. He admits, “I have brought nothing back from this journey.” It is a conclusion the reader may share.

—

Thomas McGonigle is the author of “The Corpse Dream of N. Petkov.” He lives in New York City.

William Roberson, who lives in Mastic, taught literature at Southampton College for 30 years and is now at the Brentwood campus of Long Island University. His book “Walter M. Miller, Jr.: A Reference Guide to His Fiction and His Life” came out earlier this year.