Laurie Anderson: Looking for Clues

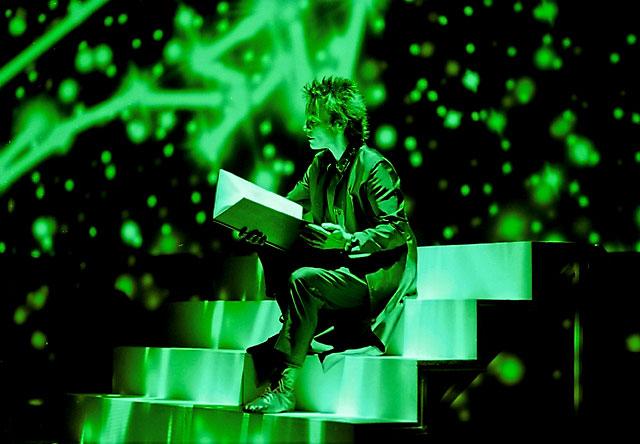

Laurie Anderson, the musician and visual and performance artist who has defied convention across a more than four-decade career, has made language and storytelling a centerpiece of her varied explorations. In a world in which the president of the United States lies more than 2,000 times per year while denouncing the news media as fake, and a foreign adversary simultaneously seeds social media with misinformation, she and other artists have ample material to consider.With “All the Things I Lost in the Flood: Essays on Pictures, Language and Code,” Ms. Anderson, who has a house in Springs, offers a career retrospective showcasing her expansive and varied oeuvre. The book features voluminous essays and excerpts thereof, photographs depicting performances given in multiple contexts across her career, and illustrations, among them a series chronicling Lolabelle, her rat terrier who died in 2011, in the bardo, the transitional state of existence between death and rebirth in Tibetan Buddhism. The latter was explored in her 2015 film “Heart of a Dog,” a meditation on love, loss, and death from a Buddhist perspective.On Saturday at 2 p.m. at Guild Hall in East Hampton, Ms. Anderson will talk about “All the Things I Lost in the Flood” with Christina Strassfield, Guild Hall’s museum director and chief curator. A reception and book signing will follow. The talk is free, but reservations have been requested by visiting guildhall.org.In her music, which may synthesize avant-garde, classical, pop, and more — “Landfall,” a collaboration with the genre-defying Kronos Quartet will be released tomorrow — Ms. Anderson regularly combines music and spoken-word meditations, her voice often electronically altered or distorted. A violinist, her instrument is also subject to manipulation, the result sometimes an entirely new or otherworldly sound. What is real, she seems to ask, in words, sounds, and images.With her late husband, the musician Lou Reed, Ms. Anderson lived along the Hudson River in Lower Manhattan. Two days after Superstorm Sandy “turned our street into a dark, silky river,” she writes in “All the Things I Lost in the Flood,” she went to the basement to check on the materials and equipment stored there. “Nothing was left,” she writes. “The seawater had shredded and pulped everything. Even the electronic equipment was now a lumpy gray sludge. At first I was devastated. The next day I realized I would never have to clean the basement again.”The day after that, she looked at a binder containing an inventory of all that had been lost. “I realized that since they were no longer objects, they had an entirely different meaning, and that having these long lists was just as good as having the real things. Maybe even better.”Language, loss, stories, impermanence, and, since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in New York and Washington, D.C., the rise of surveillance and data mining are woven throughout her work. In “Happiness,” an essay from 2001 excerpted in “All The Things I Lost in the Flood,” she writes that “every morning was like waking up in a parallel universe where it was suddenly possible that buildings and people could turn into dust before your eyes. . . . And when we look again we see the dreamlike impermanence of the world. The only words that make any sense to me now are the words of the Dalai Lama who said, ‘Your worst enemies are your best friends because they teach you things.’ ”Ms. Anderson is “in hyper-drive now,” she said last Thursday, “maybe because of some reaction to the Trump era. I’m kind of thinking, ‘What else can we do but work, make things, try to make some beautiful things?’ ”“I guess it was the last election,” she said, “that sent me over into the realm of what are stories, and what it’s like to live in a world of stories, especially when people are beginning to talk about how things end.” Such apocalyptic talk, she said, is manifested in discussions of catastrophic climate change, this month’s wild gyrations in the stock market and the uncertainty they represent, and the Doomsday Clock, which the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ Science and Security Board, citing an “obvious and imminent” existential threat of nuclear war, recently set closer to midnight. “People are seeing things in a much darker way,” she said. “Not everything has this very neat structure. Also, this was a story that a lot of people did not expect. When expectations are suddenly broken, I think a lot of people feel quite lost, it’s a ‘story emergency.’ ”She started working on the book, she said, “with this idea of what happens when the world kind of disappears, and records are an example: Records disappeared, then record stores. Books, and then book stores. It’s a world of representation. That is the jumping-off place for the talk about the book.”“It really is fun to do yet another layer of this — doing the book about the work, and the work about the book,” she said. “I like to build on things — it’s all, in a way, one long piece. I’m already seeing how it was working, understanding better what I was trying to get at.”Ms. Anderson was recently in Europe, where she began performing in the early 1970s, part of a wave of American artists who found, like jazz musicians before them, greater opportunities and larger, more responsive audiences there. Today’s political climate, she said, encourages projects beyond our shores. “I was an expat,” she said. “I got more opportunities to work in Europe than I did in the United States. . . . People were asking me constantly, ‘How can you live in a place like that?’ It was not a short answer. That’s why I wrote ‘United States,’ ” a five-record set recorded in 1983 that spanned eight hours in its live performances. “A very long piece, because it’s a complicated thing, obviously,” she said. “I feel that there’s many similar things going on now.”And not just here: A “giant fracturing” is happening in Europe as well, she said. “This carefully constructed version of your personality, the world, and suddenly you’re not so sure. . . . It’s a very intensely interesting moment now. When you no longer have the timeworn narratives you’ve been living by, that makes it a really interesting place, and you really have to live in the present, which most people aren’t doing, particularly.”Saturday’s discussion follows one in Boston on Feb. 7. Another happens at Town Hall in Manhattan tomorrow. “It’s fun to talk about something you don’t know so well yet,” she said. “You don’t have your rap down, exactly. Before it freezes into one thing, I’m enjoying what people think about it.”Along with Saturday’s talk, Ms. Anderson will offer a brief presentation at a screening of “American Psycho” on Sunday at 5 p.m. at the Southampton Arts Center. “I was one of the filmmakers asked to choose a film with ‘American values’ as part of the campaign to rebuild Sag Harbor Cinema,” she said. “I can’t stand violence, but look forward to seeing this film through a socio-political filter. This may not be completely fair to the film or to the filmmaker, but nevertheless it’s one way to see movies.”Ms. Anderson’s “Chalkroom,” a collaboration with the new-media artist Hsin-Chien Huang that she describes in “All the Things I Lost in the Flood” as a virtual-reality work in which the reader flies through an enormous structure made of words, drawings, and stories, will be on view at Guild Hall from June 2 to July 22. She plans a reading of her book in July, which she hinted would experiment with putting it into a musical context. “I left a lot out,” she said. “I wanted to focus on how words are affecting imagery. I didn’t really talk about music, and in many ways that’s my thing, being a musician.”