Carl Yastrzemski: Folk Hero, Role Model, Icon

It was 50 summers ago that Carl Yastrzemski became my first role model who wasn’t my parents. That season the Hall of Famer from Bridgehampton became a household hero by winning the Triple Crown, pretty much willing the Boston Red Sox from Nowheresville to the World Series, and turning a legion of Little Leaguers like me into forever fans. In just seven months he helped make me a better player, a better son, a better East Ender.

I liked Yaz before I saw him in action. In the winter of 1966 my father, Larry, took a break from the building of our house in Wainscott, parked outside the Yastrzemski family home in Bridgehampton, and proceeded to tell me how Yaz made himself a Major League hitter as a kid. Sitting in our Impala on School Street, I was amazed by young Carl’s routines, which seemed like the stuff of superhero comics. Hitting rocks after laying irrigation pipes on his father’s potato farm. Swinging a sawed-off bat at tennis balls fired from a short distance by grown men on the family baseball team. Swinging a lead bat hundreds of times at a tennis ball hung from the ceiling in the garage during the winter, swaddled in a sheepskin coat.

My dad was an advertising man and a lay preacher. His Yaz talk was a kind of Madison Avenue sermon. Be like Yaz, he said without saying so, and you’ll be better. I did, and I was. During my first Little League season I hit five home runs, including two in one inning, pumped by countless hours of swinging a weighted bat. I pitched two shutouts, primed by countless hours of hurling a tennis ball at a garage door to an imaginary Yaz.

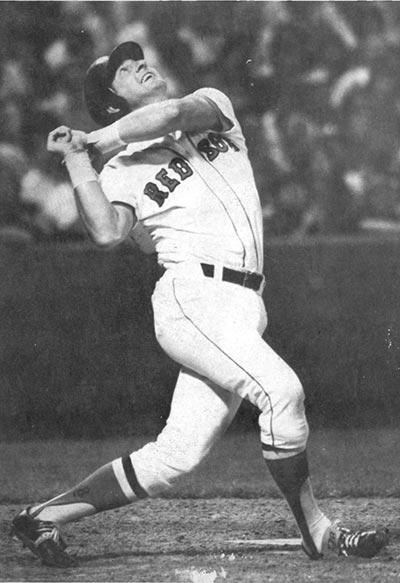

Yaz’s magical season began in Boston’s third game, when the left fielder temporarily protected a rookie pitcher’s ninth-inning no-hitter with a wide-receiver catch: over the shoulder, leaping, tumbling. By mid-July he had broken his season record of 20 homers, his strength and speed improved by an off-season conditioning program run like a Marine boot camp by a former trainer for Hungarian Olympic boxers. In mid-August he lifted the Sox after the season-ending beaning of the star slugger Tony Conigliaro, a handsome, charismatic Massachusetts native more popular in Boston than Yaz.

The next game Yaz had four hits in a win. The game after that, he hit two three-run homers in a 12-11 victory. The game after that, he reduced an 8-1 deficit with a three-run homer, then scored the winning run after being hit by a pitch and stealing second. His heroics boosted the Sox to their second long winning streak in a month, putting them in their first serious pennant race in 19 years, a minor miracle considering that in Yaz’s six previous seasons they had finished a whopping 100 games under .500.

By now the South Fork was jazzed by Yaz. His daily dramatics buzzed beaches, post offices, parties, church services, even the store where I bought my monster magazines. He was the man on Wainscott’s rectangular baseball diamond, where I copied his cooler-than-cool batting habits: rubbing dirt on hands; hitching pants; tapping helmet; raising bat high, cocking elbow to eye level; swinging with the lethal efficiency of a striking cobra. He was The Man at the Village Restaurant in Bridgehampton, where my dad and I heard salty, peppery stories from the proprietor, Billy DePetris, a high-school teammate of Yaz who was nicknamed Cobra. A true-blue capital-C character, Billy D. celebrated Boston’s unlikely success by draping the restaurant in red socks.

My father fed my Yaz fever by building me a pitcher’s mound in our Wainscott backyard. Pushing off a rubber of two bricks, I threw fastballs, curves, and knucklers to Dad, who used an oversize mitt he bought with cigar labels, kneeled on a garden cushion, and sipped a martini from a cocktail glass placed by his left leg. I’m happy to report that while I broke his toe with a pitch, I never broke the glass.

Rooting for Yaz on his home turf was over-the-moon exciting, off-the-chart thrilling. For the first time I became my father’s battery mate. For the first time I was connected to a community outside my family, my school, my church. For the first time I had a cause outside myself. On the Island I discovered I didn’t have to be an island.

Yaz saved his best for last. He had seven hits in eight at-bats in the final two games of the season, leading the Sox to the pennant on the final day. He continued his blazing pace in the World Series, hitting .400 with three homers. He couldn’t save the underdog Sox from losing the series to the St. Louis Cardinals, the first sports loss that made me cry. I consoled myself in the off-season by hitting potatoes in Wainscott fields owned by my pal Pete Dankowski’s family, reading Yaz’s autobiography, and eating Big Yaz Special Fitness White Bread (“For youngsters of all ages . . . with extra milk protein for extra muscle!”). I didn’t care that it tasted like doughy wood pulp, or that it was about as nutritious as sawdust.

My parents gave me a rare gift in 1968, after Yaz won his third batting title and saved the American League from the embarrassment of a season without a full-time hitter over .300. That October my father invited Yaz’s parents, Carl Sr. and Hattie, to eat at our Wainscott house. My mother, Pat, a native of England, treated the dinner like a State Department affair. She bought new white plates at Hildreth’s in Southampton and served ham because, after all, all Polish people like ham, don’t they, dear?

Yaz’s folks brought me a ball and a photograph signed by their son. I lost the ball in the Wainscott woods within the week. I was so embarrassed, I didn’t tell my dad until Yaz’s Hall of Fame induction in 1989. The photo remains a treasured treasure. I used it as a show-and-tell prop during my talk, “Yazzamatazz: Carl Yastrzemski as Folk Hero, Role Model, and Cultural Icon,” last month at the Bridgehampton Museum’s Archives Building. The lecture took place on Aug. 18 — 50 years to the day that Tony Conigliaro went down for the season and Yaz’s stock went up forever.

Yaz played another 16 seasons, never reaching his ’67 heights. As the years rolled by, as I graduated from pitcher to writer, I began to fully appreciate his durability and flexibility, reliability, and loyalty. He played his entire 23-year career with the Sox, tying him for second longest tenure with one team with Brooks Robinson, the Baltimore Orioles’ Hall of Fame third baseman. That’s a pretty impressive feat in this free-for-all age of free agency, when players puddle-jump in search of that extra year of contract, that extra $10 million, that last chance to be a contender.

Al Kaline, the Hall of Fame outfielder, has called Yaz the best all-around player he played against during his 22-year career, which he spent with the Detroit Tigers. Indeed, Yaz did everything well. He’s one of only 15 Triple Crown winners, one of only four players who never struck out 100 times in a season over 20-plus years, the only left fielder with 27 career double plays. He basically owned Fenway Park’s 37-foot-high left field wall, fielding tricky caroms off the Green Monster’s wooden facade, metal scoreboard, and rivets with the canny, uncanny flair of a jai alai master.

Yaz chronically tinkered with his batting approach, dropping his hands from ear to chest level to adjust for age and injury. He played through crippling injuries, often creatively. In 1971 he protected a severely strained wrist by taping the bat to his right hand, frantically unraveling the tape as he ran to first base.

Whenever Yaz was counted out, he came back with a vengeance. In 1975 he redeemed a mediocre regular season with a brilliant postseason. In the playoffs he threw out three Oakland A’s runners, including speedsters Bert Campaneris and Reggie Jackson, from left field, switching from first base for the first time that season. Running to the dugout at the end of the inning, he made sure he passed by second base so he could scold Jackson for daring to test his arm.

Yaz was a remarkably clutch hitter throughout his career. He batted a robust .414 in his 21 biggest games, including the fabled 1978 one-shot playoff against the New York Yankees. He was clutch even when he wasn’t. Sox fans still mourn his pop-up against Rich (Goose) Gossage, the wickedly fast reliever, that ended the ’78 playoff with the tying run on third base. Yet during the same game he made a terrific running catch in left field, homered off Ron Guidry, that year’s best pitcher, and singled in a run off Gossage the inning before. The night before Gossage nervously predicted that he would face Yaz with the season on the line, a tribute to a hitter who could still murder fastballs at 39.

Yaz played the game properly, without fuss or fanfare. There are no YouTube videos of him flipping his bat after a meaningless homer or pointing his fingers to the sky after a pointless single. Yet his intensity was memorably savage and occasionally funny. Luis Tiant told me, during an interview for a story about the pitcher-dominated 1968 season, about striking out Yaz three straight times on rising fastballs when he was pitching for the Cleveland Indians. Each time Yaz grunted louder, swung harder, and twisted himself tighter. By the third strikeout he could have been Wile E. Coyote tunneling into the ground like a tornado.

This special brand of stoic, manic heroism made Yaz a popular pitchman. In 1969 he cried, “I want my Maypo!” to his mom in an ad for the maple-flavored oatmeal. In the early ’70s he praised Aqua Velva, a no-nonsense smell (“just a good, clean, refreshing fragrance that makes a man smell like a man”). In 1985, two years after retiring, he sold Miller Beer without talking about beer, a strange omission for someone who stocked the Sox team plane with cases of Coors when it was a mainly west-of-the-Rockies staple. Instead, he toasted the virtues of growing up in Bridgehampton among hard-working, good-living farmers.

The Tribe of Yaz has many members from all over the map. A sports psychologist whose top leaders include Yaz, Abraham Lincoln, and Martin Luther King Jr. A lawyer who mentioned Yaz’s No. 8 uniform number during her inauguration as a Vermont college’s eighth president. A retired steel plant supervisor who insists that Yaz’s ’67 exploits inspired him as an Army intelligence officer in Vietnam. The retired Houston Astros first baseman Jeff Bagwell, who lobbied Yaz, his childhood idol, to attend his Hall of Fame induction this summer. The comedian, actor, and writer Denis Leary, who in an episode of his TV series, “Rescue Me,” honored his favorite player by singing a few bars of “The Man They Call Yaz,” the theme song for Boston’s ’67 “Impossible Dream” team. (Sample lyric: “Although Yastrzemski is a lengthy name / It fits quite nicely in our Hall of Fame.”)

Yaz belongs to the pop culture hall of fame too. He’s the only known human being to appear on “The Simpsons” (as a cartoon version of his ’73 baseball-card self, notable for his unusually long sideburns); in the film “The Shining” (as a signature on a bat used as a wife’s weapon against her dangerously crazy husband); in a Phish concert (as a muse and a mantra), and on bostonterrierhub.com (as the breed’s second most popular name).

Members of the Tribe of Yaz admire him as a gifted player with a global reach, a hero familiar enough to be an honorary uncle, a lunch-pail legend. Jews have Sandy Koufax, Italians have Joe DiMaggio. The rest of us, including Poles and English-Germans, have Yaz.

Yaz became my go-to guy again during the 2007 playoffs, when the Red Sox were down three games to one in their series against the Cleveland Indians. I watched the fifth game at my mother’s house while eating ham on china she bought for our 1968 State Department dinner with Yaz’s parents. After the Sox won, Mom and I decided to repeat our ham-and-white-plate special. Result: The Sox won both games on their way to their second world championship in three years and their third in 89 years.

Yes, even 24 years after he retired, even 40 years after he became my third role model, Yaz had some Major League mojo.

A former resident of Wainscott, Geoff Gehman devoted a chapter to Carl Yastrzemski in his memoir, “The Kingdom of the Kid: Growing Up in the Long-Lost Hamptons” (SUNY Press). He lives in Bethlehem, Pa. His email address is [email protected].

--

Correction: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this article referred to Red Sox pennants hung outside the Village Restaurant. Billy DePetris had hung actual red socks outside the restaurant.