Myth and Mystery

Myth and Mystery

“Origins of the Past”

Edited by Tom Twomey

East End Press, $40

Chroniclers, diarists, and historians often must have felt what East Hampton’s master mechanic Nathaniel Dominy IV scribed on the rear of a metal tall-case clock dial he made in 1788: “Where oh! Where shall I be when this clock is worn out?” Heaven may have been the answer Dominy was suggesting, but to the recorder or analyst of history the perfect solution is to be published and remain a viable source of information.

Dominy’s late-18th-century clocks are still keeping time — the pendulums swing back and forth, the rhythm of the tick alive and well. And the writings of many of our past regional historians remain a constant resource to understand the very complicated creation of East Hampton Town. Their books are not worn out. Their words transmit many thoughts that have become part of the myths and realities of East Hampton’s past.

It is to our present historians that the task of sorting and verifying these authors’ works falls. It is a job of sifting through documents that often were not available to past generations and reformulating old information with recent research. Historians are forever rediscovering bits of the past and thankfully startling us with their fresh interpretations.

The South Fork of Long Island has been well chronicled by several 19th-century historians, William S. Pelletreau, Henry Hedges, and George Rogers Howell in particular. In the 20th century, James Truslow Adams, Harry Sleight, Jeannette Edwards Rattray, and Abigail Fithian Halsey added greatly to our understanding of our communities in earlier days. Today, Timothy Breen, Faren Siminoff, John A. Strong, and David Goddard have produced important books that involved endless research and innovative thinking.

But East Hampton lacks a comprehensive modern scholarly history. Our last history of East Hampton Town was published 60 years ago. So many important archives have come to light since then; so many ideas have been developed about the Atlantic world and the great migration of the 17th century. We all await the next “History of East Hampton.”

Luckily a local institution has been compiling volumes of selected writings from both past and present authors to help quench the thirst of those who love the stories of old-time East Hampton. The East Hampton Library has been in the lead regionally in supporting the publication of books on local history. Besides being the keepers of a renowned resource of East Hampton material in its Long Island Collection, it has consistently held public programs that have focused on local history writers.

Indeed, the library’s first volume of East Hampton historical essays was “Awakening the Past: The East Hampton 350th Anniversary Lecture Series — 1998,” a celebration of scholars and history writers who brought a worldview to local studies. This book was quickly followed by three other compendiums, including the writings of Henry Hedges, Jeannette Edwards Rattray, and a gathering of 19th-century essays by men of letters like Walt Whitman and William Cullen Bryant.

Today we are looking at the fifth in the library’s series, “Origins of the Past: The Story of Montauk and Gardiner’s Island.” It was a brilliant idea to choose two of the most romantic areas within East Hampton’s borders for examination. Both have had their share of myth and mystery. Just say “Gardiner’s Island” and everyone has a tale to tell, be it of buried pirate treasure or a bit of bragging about once being on the island, illegitimately or not.

The book is divided into five parts, starting with “The Montauketts: Montauk’s First Inhabitants.” Gaynell Stone and John A. Strong are the pre-eminent scholars of East End native peoples and have consistently ignored the patronizing Eurocentric approaches that most local histories engage in. They offer the reader a well-documented paper that is as vivid as it is factual. Following Ms. Stone and Mr. Strong is a contemporary account of the famous 18th-century Native American missionary, the Rev. Samson Occum, who recorded some of the social customs of the Montauketts. Both of these pieces are very important windows into the First People.

Part II includes discussions of the role that local wampum making had on the destinies of the Montauketts and the Shinnecocks. Sad destinies replete with European greed and manipulation. Wampum beads were made out of purplish-black or white whelk and quahog shells. The shell fragments were arduously drilled, rounded, and polished. Native Americans used these beads as money, and after white contact some were woven into belts as treaty documents. The essays by Lynn Ceci and Elizabeth Shapiro Pena are vital to our understanding of what wampum meant to the original inhabitants and how it became lusted after as the currency of the coastal colonists.

The book’s editor, Tom Twomey, the chairman of the East Hampton Library, who spearheads these volumes, next introduces the reader to Part III, where we find several historical fragments that give Lion Gardiner a voice, as well as some useful history of the Pequot War and two rare impressionistic essays relating to the Montaukett Pharaoh family.

This acts as an introduction to Part IV, “The Legend and Lore of Gardiner’s Island,” in which the individual articles include a mixture of myth and scholarship.

And how do we escape the legends of Gardiner’s Island — and do we want to? Mr. Strong’s incisive lecture from the 2009 Stony Brook University conference “Worlds of Lion Gardiner (1599-1663): Crossings and Boundaries” is the best writing we have on the personality of Gardiner and his relationship with the great sachem of the Montauketts, Wyandanch. Its illustration of Gardiner’s business acumen may taint their sentimental friendship, which has often been depicted in the past.

This lecture is a very important addition to this anthology. As is Roger Wunderlich’s “ ‘An Island of Mine Owne’: The Life and Times of Lion Gardiner, 1599-1663,” a clearheaded history of Gardiner’s purchase of the island. Some of the older selections are included to focus on the lore.

The final section, “Montauk Through the Ages,” includes eight pieces, one a full chapter (over 100 pages) by the noted historian David Goddard, whose splendid “Colonizing Southampton: The Transformation of a Long Island Community, 1870-1900” was published two years ago by the SUNY Press. Mr. Goddard summered in Southampton for a number of years and became intrigued by the history of land ownership, the development of the South Fork’s summer colonies, and the histories of two of its most famous golf courses.

Titled “On Montauk,” Mr. Goddard’s article is positively the best and most accurate research done on the convoluted story of how this Montaukett land became part of East Hampton. The obtuse twists and turns, the cast of characters, and the fraught relationships between supposed owners is almost operatic. Only a scholar with a sure hand could keep all these players in order. If there is one article you must read, it is this one.

There are other jewels in this section. Jeff Heatley’s “Col. Theodore Roosevelt, the Rough Riders, and Camp Wikoff” is sharply written and combines a number of very informative quotes to fully put a face on this almost forgotten war (the Spanish-American) and a rather overlooked part of Montauk’s history. It is entertaining to see Walt Whitman, Henry Osmers, and Jeannette Edwards Rattray sharing these pages of Montauk stories, and what fun to imagine them trading tales.

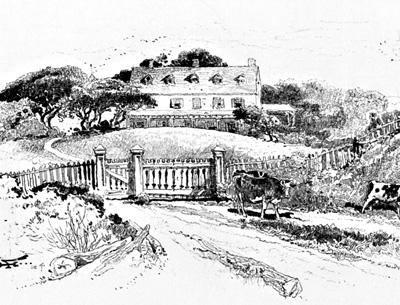

I was pleased to see one of my favorite pieces of old-time travelogue writing show up in this last part. First published in 1871 in the New Monthly magazine, the painter Charles Parsons gives us a visual essay on what Montauk looked like in the fall almost 150 years ago. Here, seen by an artist’s eyes, is all the romance that a rustic retreat could rustle up. “Mile by mile we walked by the sea; the beach was a pure clean sweep, free from seaweed, pebbles, or stones. Tiny sandpipers were running along in front of us, following the curves of the incoming and receding waves.”

This world may be lost now, but it lives on like an old Dominy grandfather clock. The words are here in this collection of writing, ready to seduce or enlighten us. It is the history of East Hampton ticking away. It feels good to have it saved within the boards of a book. These days, could anything be more historic than a book?

Richard Barons is the executive director of the East Hampton Historical Society. He lives in Springs.