Readings Ramp Up in Gansett

Readings Ramp Up in Gansett

Sunday marks the return of the venerable Poetry Marathon in Amagansett. This year’s series of readings starts at 5 p.m. that day with Joanne Pilgrim, an associate editor at The Star, reading from her verse, accompanied by Jan Grossman, a past fiction and poetry reviewer for the Rockefeller Foundation who has had poems published in American Arts Quarterly, among other journals. The readings are held in the East Hampton Town Marine Museum on Bluff Road, and a reception follows each.

The free series, organized by Sylvia Chavkin with the help of Annalee Collins, continues on July 19 with the playwright Joe Pintauro and the India-born Meena Alexander, whose collections include “Birthplace With Buried Stones.” The esteemed duo for July 26 is Grace Schulman, a professor of English at Baruch College and Springs part-timer whose latest book of poems is “Without a Claim,” and Kimiko Hahn of the North Fork, whose nine collections include “Brain Fever,” published last year by Norton.

Carol Sherman and Daniela Gioseffi are in store for Aug. 2, with George Wallace and Geraldine Green the following week. The series wraps up on Aug. 16, when Virginia Walker, whose latest is “Neuron Mirror,” and Carole Stone, the author of, most recently, “Hurt, the Shadow: The Josephine Hopper Poems,” read from their work.

Over at the Amagansett Library, the Authors After Hours series is back with another strong lineup of summer readings. It begins on Saturday at 6 p.m. with A.M. Homes, the East Hampton author of pungent short-story collections like “The Safety of Objects” and novels of how we live now, the most recent being “May We Be Forgiven.”

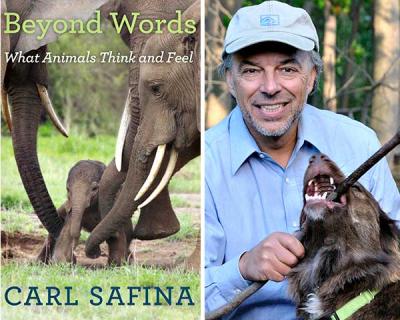

Following her on July 18 will be the hamlet’s own Carl Safina. The naturalist will talk about his new book, “Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel.” On July 25, also at 6 p.m., Chris Pavone will step to the lectern to discuss how his own experiences have informed his best-selling thrillers, “The Expats” and “The Accident.”

On Aug. 1 Tom Clavin will examine adapting books for the big and small screens, which is happening now with two of his books written with Bob Drury, “Last Men Out: The True Story of America’s Heroic Final Hours in Vietnam” and “The Heart of Everything That Is,” about Chief Red Cloud.

Also that month, on the 15th it will be Anna Bernasek and D.T. Mongan on “All You Can Pay: How Companies Use Our Data to Empty Our Wallets,” with the political cartoonist and journalist Ted Rall discussing his forthcoming “Snowden” the following week, and Christopher Bollen, the author of a new suspense novel, “Orient,” on the 29th.