Funereal Ins and Outs

Funereal Ins and Outs

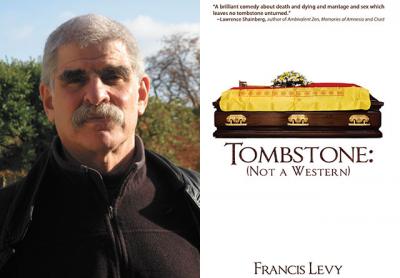

“Tombstone:

(Not a Western)”

Francis Levy

Black Rose Writing, $17.95

To be buried or cremated, that is the question. “Tombstone: (Not a Western)” is an absurdist tour of one man’s neurotic approach to his own demise. Our mapless guide is the unlikable but very funny Robert Bernstein, a skirt-chasing, peep show-visiting, Bukowski-reading baby boomer with a serious case of male pattern self-absorption who is constantly trying to get a leg up in a world full of barriers to getting your obit in The New York Times.

The novel begins in New York City with a shopping expedition: He’s out to buy a coffin. Maybe. But maybe not: “I know what I’m like and people are going to get over me pretty quickly. They won’t need a catered affair to realize they’re better off without me.”

Bernstein plumbs the depths of death-related duality: Does he wish to be cremated or to be buried along with his wife of 30 years? Cremation implies a rebellious turning away from the strictures of his wife and culture. He is, after all, claustrophobic. Burial, however, puts him in the fray of making “arrangements” — expensive funereal ins and outs laden with decisions that point to social class and family dynamics. Will his estranged kids even come to his funeral?

Our dubious hero collects his wife, Marsha, and chases these matters west of New York to El Rancho de Campo in Arizona, an all-inclusive resort for death tourism, “the world’s only resort devoted to death which also happened to feature a 27-hole golf course, a dude ranch, multiple cemeteries whose gravesites all boasted long-term care contracts and a slaughterhouse for grain-fed beef, a gesture to Stendhal’s famous novel, called ‘The Slaughterhouse of Parma.’ ” For example, they pick you up from the airport in a hearse, ply you with “samples of a potent cocktail made from embalming fluid” in the hotel lobby, and offer such seminars as “Stiff as a Board: Tantric Sex in the Afterlife and Beyond.”

Once at Rancho de Campo, the pacing of the book drags in a no-death-related-shtick-left-unturned litany, where joke setup and punch lines replace plotting for a portion of the narrative. But then again, maybe that’s life? And Mr. Levy is funny! His nimble facility with language contains the wry and the absurd. As parody, Rancho de Campo pokes at the commodification of death, and thus at the outer limits of commodification in general. Satire rounds up Mr. Levy’s theme, the human impulse to control the mystery of death rather than seek to come to terms with it.

In the era of the #MeToo movement, routine sexual objectification of women as the narrator moves from lust object to lust object might feel a bit gratuitous, since the ogling, albeit satirical, does little to deepen the author’s theme. But in the main relationship in the novel, between Bernstein and his wife, there is a surprising sense of tenderness hidden in Mr. Levy’s satire that emerges in spite of a kind of tacit enmity between them.

“We had never been into outright sadomasochism. That would have been a commitment to some form of pleasure that both of us had always been unwilling to make. Instead we’d held to the kind of constant bickering that freed us from the burden of having to decide whether we had any feelings at all. You get used to lots of things and the constant criticizing and feeling put-upon was what we called home.”

Once out of Rancho del Campo and onward to . . . spoiler alert . . . the afterlife, he has his wife constantly in his peripheral vision as they make their way to whatever comes next. For better or for worse, he is not in whatever it is alone. This forging ahead beyond the end defines the attitude of exploration that marks the novel.

“While I hadn’t wanted to die when I was alive, I’d always thought that the one good thing about death was that you got to slow down and relax — which is why I was surprised that in the afterlife I still found my mind racing.”

Mr. Levy’s project is an earnest and driven seeking. All those jokes are mined as fuel to keep the inquiry moving forward.

Those who are there — facing down “arrangements” or starting to take a sidelong look at mortality — will enjoy the company of Mr. Levy’s wacky, all too mortal machinations on the vagaries of death. In the ironic words of his vehicle Robert Bernstein: “The desire to have a proper funeral made me want to live.”

Evan Harris is the author of “The Quit.” She lives in East Hampton.

Francis Levy, a Wainscott resident, is the author of the comic novels “Erotomania: A Romance” and “Seven Days in Rio.”