My Affair With ‘The Affair’

My Affair With ‘The Affair’

I hate rubbernecking. I think it’s mean to stare down a waitress after she’s dropped a tray of dishes, cruel to slow down to inspect a highway wreck, stupid to obsess over the extramarital flings of the C.E.O. of the U.S.A.

Yet I gladly rubberneck “The Affair,” the Showtime series that spins around two couples who split but can’t quit each other after a summer infidelity in Montauk. For four seasons I’ve avidly followed four basically decent people who keep making disastrous mistakes: abandoning a child to get mentally well; burning down a house to deny and confirm a family curse; stalking a stalker who may not be a stalker. Alison, Cole, Helen, and Noah are the black sheep of my TV ark, the rogue surfers of emotional tidal waves that crash into my life on and off the South Fork.

My affair with “The Affair” began on Halloween 2014, a day of expected and unexpected treats. I was visiting friends in Wainscott, where I lived from 1967 to 1972, when I discovered all my major passions, from baseball to sex to writing. That morning I satisfied my love for nature by walking the Walking Dunes in Napeague, the Sahara stand-in in Rudolph Valentino’s silent film “The Sheik.” I hiked over the mountainous mounds into the sandy bowl where I once ate hot dogs grilled on a hibachi and listened to twilight ghost stories. All that trudging made me hungry, so I headed to the Clam Bar on Napeague for Manhattan chowder, sweet potato fries, and my first-ever midday beer. Driving back to Wainscott I saluted another Napeague landmark, the Lobster Roll, where I ate my first lobster roll and met my first lover.

That night I accidentally tuned into a rerun of the first episode of “The Affair,” which opens, lo and behold, at the Lobster Roll. Not only that, the eating place is the meeting place for the titular cheaters: Noah, a bored Brooklyn writer and teacher summering with his family in Montauk, and Alison, a Montauk-raised waitress and nurse mourning her drowned son. In an instant a sexy coincidence became seductive.

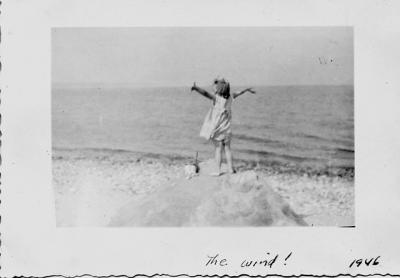

“The Affair” sucked me into its riptide of misery, ecstasy, and murder mystery. What really sucked me into the show was the undertow of my memories of Montauk, where I first made love, flew a kite, bodysurfed, clammed, clam baked, picked black-eyed Susans, and roller-coastered on the slaloming Old Montauk Highway. My senses go haywire on the East End’s East End; the Montauk Point panorama makes me feel enshrined in one of those huge Kodak photographs that illuminated Grand Central Station.

“The Affair” is a handsome exploration of ugly behavior. Writers and actors expertly examine the detritus of divorce: the guilt, the relief, the guilty relief, the torn treaties, the lashing limbo. I know because I’m one of divorce’s children. My parents’ 15-year marriage dissolved after my father sold our Wainscott house without telling my mother. At the time he desperately needed money after losing his job and $10,000 of his kids’ college tuition on a bad business deal in Montauk. The bickering between Mom and Dad escalated after he married the owner of a bigger Wainscott home, which I passed every time I visited Beach Lane Beach. Their arguments were aggravated by their loneliness. Dad missed his children; Mom missed her mate.

My parents made peace after Dad’s second divorce. Three months before he died, they agreed to share a gravestone. Three months later, she came with me to see his corpse. She wanted to comfort her son and say goodbye to the only man she truly loved.

“Affair” characters bury axes with their exes, too. Alison and Cole buy and restore the Lobster Roll, which replaces the Montauk horse ranch he lost with his brothers and mother. Helen nurses Noah out of a psychotic haze caused by a nearly fatal stabbing; he swears his attacker is his alleged stalker, a jealous prison guard. Helen is essentially repaying Noah for essentially saving their family by confessing to a crime she essentially committed.

Noah’s hell is very much like my father’s. My dad mastered pretty much everything: selling ads, playing tennis, singing barbershop, telling stories, writing whimsical animal poems worthy of Ogden Nash. The only things he couldn’t master were his alcoholism and his manic depression. Living alone in Hampton Bays after his second divorce, he substituted wine for lithium, which led to a stroke, which led me to move him into my apartment. Embarrassed by feeling like a burden, he disappeared for a month, living in shelters and parks in Manhattan, where he’d worked for four decades. He was rescued by psychiatric nurses, social workers, and loved ones who knew he was a good guy in a bad way.

Noah pays dearly for his affair. He turns it into a best-selling novel that angers Alison, who has a child with Cole that Noah thinks is his for two years. My affair was a lot less costly. Helen — yes, she shares the name of Noah’s ex — and I had four nights of passion 12 years after one night of passion that climaxed a year of beautiful mental foreplay. She was tickled when I told her I decided to scratch our itch while I watched Clint Eastwood and Meryl Streep do the same in “The Bridges of Madison County.”

After our erotic reunion, Helen returned to married life in Texas. I returned to single life in Pennsylvania, where I’d met Helen and the very decent fellow I always knew she would marry. Over the next 20 years our friendship deepened while our yearning lingered. We never regretted our affair; we only regretted that we didn’t pursue a romance when she was single. We continued to have refreshingly frank, funny phone conversations until three weeks before her sudden death less than a year after her daughter’s sudden death.

I hear myself talking to Helen and my other exes whenever “Affair” characters ruthlessly inventory their relationships. When Noah and Helen fill a favorite restaurant with confessions, accusations, and resolutions, it reminds me of the last great chat I had with my former wife. It took place, lo and behold, in our favorite restaurant right after I told her, in our therapist’s office, that I didn’t want to be married anymore. We were so relieved that we still liked each other, we hurried home to make unfettered, unmarried love.

It took me 30 years to realize we were auditioning for “The Affair.”

Geoff Gehman is the author of “The Kingdom of the Kid: Growing Up in the Long-Lost Hamptons” (SUNY Press). He lives in Bethlehem, Pa., and can be reached at [email protected].