African Childhood, European Roots

African Childhood, European Roots

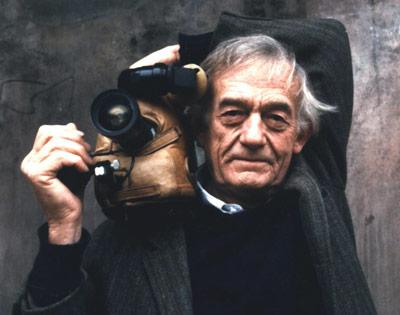

“Beautiful Tree, Severed Roots,” the cinematic journey Kenny Mann will offer viewers on Sunday at the Bay Street Theatre, is not strictly a memoir, although it is about her past. “It’s a story of identity,” she said, adding that others will be able to relate to the documentary. “So many people today are misplaced, it’s very relevant in today’s political climate.”

Ms. Mann was born and raised in Kenya, the child of Jewish refugees who escaped the Holocaust. “It’s an unusual story,” she said. “My parents were incredibly charismatic.” Her mother, Erica Schonbaum, whose last name means “beautiful tree,” was from Romania, and met Igor Mann, who was Polish, in Bucharest. When the Nazis invaded, the couple escaped thanks to faked papers that were bought and paid for. “My mother had two birth certificates,” Ms. Mann said. “They had to tell so many lies to survive.”

The couple ended up in an Israeli refugee camp for a year. “But the British were looking for educated people,” Ms. Mann said. Her father was a veterinarian and an animal husbandry expert, so her parents were sent by troop ship to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). “He became world famous for his ideas,” Ms. Mann said. “He was very, very far advanced, talking about ecology long before it was a buzzword.”

Her parents settled on a cattle ranch on Masai land in Kenya, on the Athi River, where Ms. Mann was born and named for her parents’ adopted country. She lived in Kenya until she was 24, knowing very little about her ancestral past. “There were no family photos, no relatives except my grandmother,” Ms. Mann said. “There was a big vacuum.”

It wasn’t until she started going through family documents that Ms. Mann realized how deeply her Eastern European roots ran, and her sense of identity was challenged.

“I wasn’t tormented by it,” she said, but it did raise questions. “Who are we, really? I was a non-practicing Jewish person, but I didn’t feel Jewish. I wanted to find out more.” She was able to interview her mother extensively before she died in 2007.

Her father had died in 1986, but information about him is still coming down through several interesting pipelines. “I discovered that Dad’s niece was a well-known journalist in Holland. Before her parents were taken away by the Nazis, her mother had yelled out to her, ‘Don’t worry, you will survive. Your uncle in Africa will send you pineapples.’ ”

Ms. Mann has been shooting this documentary, her seventh film, for the past six years. “Kenya is so incredibly photogenic,” she said. “But the film isn’t typically what you would see. It’s visually surreal. I wanted it to be more poetic and metaphorical. It’s built a great deal on memory and I wanted to avoid the usual, educational documentary.”

Ms. Mann’s last film, “Walking With Life: The Birth of the Human Rights Movement in Africa,” won several awards.

She heads up her own film company, rafIki Productions. “Rafiki is the Kiswahili word for friend,” Ms. Mann explained on her Web site. Her nickname as a child was “Iki,” and she chose to “name my company rafIki as a fun combination of my name and my roots.”

The Bay Street Theatre program will begin with a performance by Masai dancers, courtesy of Association of Maa Abroad, followed by a screening of about 40 minutes of the unfinished documentary and a brief discussion about identity.

“Because of the Internet, we are hearing that allegiances and nationhoods can change, without being geographically tied. But the more that happens, are we programmed to need that personal identity more than ever?” she asked.

“For anyone who is curious, the journey, both physically and emotionally, has been necessary to see what I can choose to accept or reject. It’s led me to see that I am a global citizen. But knowing one’s roots adds a dimension to life, even if they are very distant roots.” And even if those roots, like Ms. Mann’s, have been severed and left behind.

The theater’s box office will open at 1:15. The dance performance and the film begin at 2 p.m.