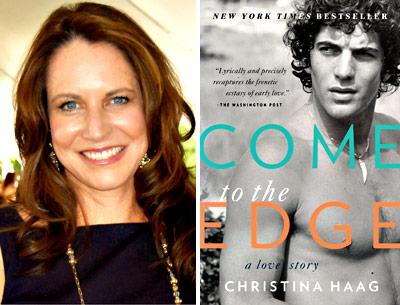

A Kennedy Love Story Told With Restraint

A Kennedy Love Story Told With Restraint

While many Americans had some memory of or reaction to the recent 50th anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Christina Haag had a more personal investment than most in the tributes and recreations of the events that day.

Only a child herself at the time, she would come to know, befriend, and then fall in love with the president’s only son, John F. Kennedy Jr., a story she recounted as part of her memoir, “Come to the Edge: A Love Story,” published by Spiegel and Grau in 2011.

She said in a conversation on Friday that the media coverage and presentations of the life of the former president were mostly familiar to her, but found the “American Experience” biography broadcast on PBS very moving. “They showed how as a boy he grew up, and in the pictures his mannerisms reminded me of John.”

The dramatic loss of his father when he was just 3 years old was “incredibly tragic, but John was a positive person. His mother kept his father’s memory alive in a loving way, but they didn’t live in the past.” She said Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis told stories at the dinner table and kept his presence there among them.

“I think John was curious about his father and did have a few stories of his own” that he remembered. “He was proud of the things he accomplished, like the nuclear test ban treaty.”

Online, she found a home movie of the extended Kennedy family taken when the younger Kennedy was 12 with his cousins and mother in the summer at Montauk. The film shows them diving in the water. It was particularly meaningful to her because of where she wrote her book.

Ms. Haag could have chosen Greece or Italy or any number of writers’ retreats to write her memoir several years ago, but she chose Montauk and Noyac as her places of inspiration, cementing an affinity for the East End sown in her from her first summer in Quogue when she was an infant.

“It was instinctual. I spent my whole childhood out there every weekend and in the summer,” she said of her decision of where to write the book. “Come to the Edge” is a chronicle of her life, with the centerpiece being her long friendship and then five-year love affair with Kennedy. The best seller was well received for its insights into his life and personality, told with restraint.

Ms. Haag will be a featured author at the John Jermain Memorial Library’s annual authors lunch on Sunday from noon to 2:30 p.m. at the American Hotel. She said that the Sag Harbor library and the East Hampton Library were two of her refuges when she needed to take a break from the solitude of writing.

Having kept journals since her elementary school days at the Convent of the Sacred Heart in New York City, she said she began to feel an urge to bring them all together in book form around 10 years ago. It was more challenging than she thought, however, to cull all of the material into a cohesive whole. “It was a knock at the door that kept getting stronger.”

She studied theater arts and English at Brown University and went on to Juilliard to pursue her love of acting, but “as I grew older my love of writing also became stronger.”

She was living in Los Angeles primarily but came back east regularly, and trips to visit friends on the South Fork were plentiful. “I wrote chapters in Sag Harbor and Montauk early on, and the writing there came easily.”

On the West Coast it was a different story. “I’m not a great multi-tasker. I was in a play and I thought, ‘After the play opens I’ll be writing again.’ But the play was not a good play, and I spent most of my energy on how to make it better. By this point, I had a book deal.” It was time to get serious.

She first rented a cottage on Fort Pond in Montauk in the year before the Surf Lodge opened and through the year after, catching only the beginning of the evolving scene that became “hipster Montauk.” Fortunately, it was still quiet on the off days. She spent downtime with family and friends in East Hampton, Bridgehampton, and Amagansett. After a few weeks of kayaking on Fort Pond, “one day I stopped in the middle of the water and looked around and realized it looked similar to a place John and I water-skied on Martha’s Vineyard.”

As the book progressed, she continued to find comparable inspiration there and in Noyac. “The walks I took — by the wide beaches at dusk, on the wooded trails and the paths between the raspberry bushes at Quail Hill Farm — were as much a part of writing as sitting down with my pen. . . . It would have been a different book if it had been written somewhere else.”

She needed the space and the breaks from writing, which could become intense. The people she wrote about — “John, my father, Mrs. Onassis, my grandmothers” — became “very vivid, as if they were sitting by me as I wrote. They are there with you again for a time, and there is joy and sorrow in that.” At the same time, she was revisiting her “25-year-old self and reaching across the table — and in the end, understanding.”

Given the subject matter and the infinite fascination the world has with the Kennedy family, she found herself in the whirl of book publicity, appearing on national broadcasts such as the “Today” show and in print in Vanity Fair and other publications. “Certain media outlets have their Kennedy story and they want to use you to tell their story.” She said that part was challenging, but she was glad she did it.

Ms. Haag said that to this day some members of the paparazzi continue to recognize her (surely in part from her notoriety in the late 1980s as the girlfriend of People magazine’s “sexiest man alive,” an honor Kennedy received in 1988). That recognition has increased since the book was published. “People often want to come up and talk to me about him.” She said they respond to the description of Kennedy and his family as well as the love story in the book.

This Thanksgiving, she was at a party and a well-known gossip columnist approached her to tell her she had spotted Kennedy with her early in their relationship. The columnist recalled that when Kennedy saw her watching them, “he put his arm around you and whisked you away. I asked him later, ‘Is this a scoop or should I let you live your life?’ He said, ‘This is special, could you leave it alone?’ ” Which she did.

The inside story Ms. Haag tells demonstrates remarkable discipline and respect. She managed to provide enough details to make it engrossing without risking overexposure. She credited her editor and a dedicated group of readers she selected from her friends to help her gauge which incidents were most compelling and how best to present them. One of her favorite reactions to the book was from a producer friend who said, “It reads like a goodbye you didn’t get to say.”

A shorter work will be in “The Brown Reader” anthology, to be published by Simon and Schuster in May. Ms. Haag continues to act and was recently featured in “Law and Order: SVU.” And she is currently at work on a historical novel set in New York in the 1880s. It is one she hopes to finish writing back on the South Fork, where she can take her breaks at Provisions, Indian Wells Beach at dusk, Yoga Shanti, Mary’s Marvelous, or a few of her other favorite places.

The John Jermain Memorial Library’s lunch also features Chris Knopf of Southampton, whose latest book, “Cries of the Lost,” won a Nero Award for best American mystery. The cost is $50, and reservations can be made through Chris Tice at [email protected].