Opinion: Parrish Re-Hangs Its Permanent Collection

Opinion: Parrish Re-Hangs Its Permanent Collection

The new Parrish installation of its permanent collection galleries, which is taking shape to be an annual fall event, offers some delightful surprises and some disappointments. The museum continues to attract major gifts and acquisitions to its new state-of-the-art facility in Water Mill, but the 2,700 works in its holdings are not all created equal and some seem just plain tired to eyes accustomed to the usual East End themes and memes.

First, there is the good news. It depends on how you navigate the rooms, but the ones closest to the double gallery separating the permanent collection from the temporary shows are the strongest. One side is devoted to Fairfield Porter and Robert Dash in visual conversation with each other. The other has a series of landscapes and cityscapes with an eclectic mix of older and more contemporary artists that looks even better the longer you linger.

During Dash’s earlier, more realist, days, he owed a great debt to Porter’s own distillation of artists such as Pierre Bonnard. He stayed at the Porters’ house in Southampton during the early days of his visits here before he created Madoo, the garden conservancy in Sagaponack.

While Dash echoes the Porter style, he does not mimic it, adding more open interpretations of color and form to create a more modern expression wholly his own. It is not as evident in a spare interior from 1965, which has a more Impressionistic feel. But just the simple choice of subject matter, a room entrance framing another one in the distance, is a more abstract construct than the more straightforward Porter subjects surrounding it in the gallery. Looking at it, one is far more aware of the painter and his choices, and even simple geometry, spaces and voids, lines and structure, than the more traditional landscapes and interiors of Porter.

Two other works from a decade later take these early departures much further, using the play of natural light as a launching point for a more individual interpretation of an outdoor terrace and a portrait of John Ashbery.

The room is a well-edited anthology of Southampton-style realism and another example of Porter’s enduring legacy through those who followed him.

The other exceptional room, titled “Painting as Metaphor,” again brings Porter together, not with his followers, but with those who tackled similar and not so similar subjects within the landscape genre. It’s a pretty room and can easily be enjoyed and then departed, but there is a lot going on in here.

Upon closer reflection, the superficially neutral subjects are country and cityscapes during times of distinct change and possibly upheaval. It is probably noticed first most prominently in Porter’s cityscape from around 1942. One of the few canvases in the room to portray people, the grouping of figures and their expressions reveal much of the uncertainty and hardship of the time.

The three figures, a matronly woman, a man in a dress coat and hat, and a child in the distance, could be a family in another context, but here they seem to be archetypes, removed from each other to lend symbolic weight and psychological complexity. The isolation of the modern city and the divisions taking place in families from the war effort no doubt inform this work.

In the background, modern high rises loom over the tidy block of brownstones and an old neighborhood begins to lose its character. Porter moved permanently to Southampton in 1949.

Implied metamorphosis is all over this room. It figures into the earliest painting as well. William Merritt Chase’s image of Bensonhurst in an oil sketch from 1889 shows a bucolic waterfront, developed only with a promenade and in no way recognizable in the cityscape of today.

John Sloan’s depiction of Gloucester from about 1916 would lead one to believe he had been in France prior to painting it. The avenue he represents has the feeling of Nice or other southern French seaside towns or cities. As a new, racy convertible charges down the street, it kicks up dust in the direction of a horse and buggy and ruffles the feathers of some birds gathered there. Flaneuses promenade their way down the sidewalk, revealing their ankles in a modern style. It is not quite the Roaring Twenties yet, but this is already modern America in its infancy.

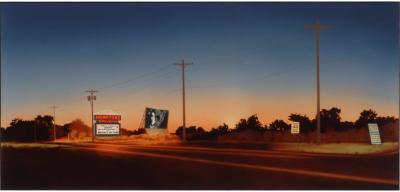

As the empire rises, so does it fall, and with it outmoded technology and amusements. In what could have been merely a honey-coated nostalgia piece, Howard Kanovitz takes the complexities of post-Modernism and locates them, writ large, on the South Fork landscape. Even a rural paradise is subject to the shifting needs and wants of its populace, and what seemed state of the art a few decades ago becomes a lumbering dinosaur when tastes change. In “Hamptons Drive-In,” a photorealist work from 1974, Kanovitz presciently captured the dusk of that Bridgehampton landmark, helpfully imbuing the horizon with the salmony-orange glow of a Hamptons sunset at last light.

Perhaps realizing that this might be his magnum opus, he painstakingly documented each step of its creation in a documentary also in the Parrish’s possession. The film on the drive-in screen, caught in a still and helpfully announced by the depicted sign, is “Cabaret,” set in Weimar Germany, another time and place where society and the landscape would be radically altered within the next decades. As if all this foreshadowing were not enough, a small sign at lower right announces the availability of stores by Kimco, the developer that transformed the site into the present Bridgehampton Commons, home to such country pleasures as Kmart, Staples, and The Gap. Once seen in this light, every painting seems to tell a similar story, some more subtly than others but none as powerful as this.

The other rooms might be termed the eat-your-vegetables rooms. They dutifully pay homage to some of the titans of the East End art-making tradition, or in some cases the titans of Parrish patronage. That is not to say that Esteban Vicente does not deserve his due, but the museum may be risking overkill in its effort to show appreciation for his foundation’s financial support for its new home. Still, even the room devoted to his circle brings several exciting pieces out into the light, including some great works on paper by Robert Motherwell, Perle Fine, Norman Bluhm, Lee Krasner, and James Brooks.

Other rooms bring out new aspects of the museum’s sizable collection of William Merritt Chase and a few other themes that continue to be relevant from the mid-20th century to the present, such as the artist at work in his studio and the enduring relationship between practitioners of arts and letters.

We should look forward to future iterations of these installations. They will no doubt continue to tell both the story of East End artists and the Parrish’s evolving role in presenting them.