Barney Rosset’s Great Wall May Come Down

Barney Rosset’s Great Wall May Come Down

This past year, some of recent history’s more creative and flamboyant spirits have discovered and interacted with an eccentric and eclectic monument to the artistic pursuits of one of their own. That the artist was Barney Rosset, known primarily for his championing of literature and film, surprised most. But the artifact he created stunned all.

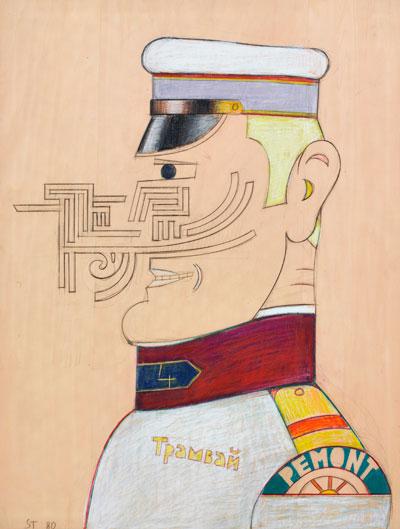

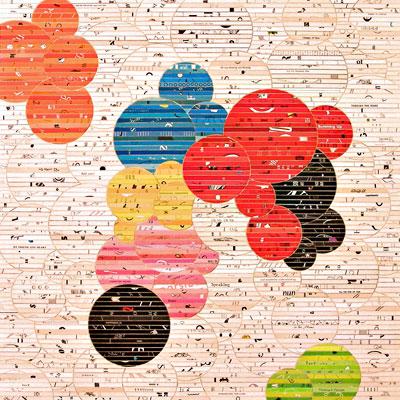

What they saw was a 12-by-22-foot wall-spanning mural, as ambitious as it is idiosyncratic, and a true emblem of the 20th century, even though it was conceived during the 21st.

Mr. Rosset, who died in 2012, worked on the mural in the last few years of his life. Astrid Myers-Rosset, his widow, said it was in 2008, after Rosset sold part of his archive to Columbia University, that he started the project. “With everything gone, the space opened up and he rediscovered the wall. He started the mural and it was three years going on.”

Those who came to see it were invited and filmed by a team that included Williams Cole, David Leitner, and Sandy Gotham Meehan. They aimed to capture both the viewers’ initial “pure response to it” and their reflections on it after they had a chance to observe all of the detail. “Barney’s Wall,” a documentary about the wall and its meaning to this group of people, will serve as a salute as well as a testament should something happen to it, a possibility that is becoming ever more likely unless someone steps in to preserve it.

Throughout his life, Rosset courted controversy through his love of literature and film and his struggles to ensure censorship did not silence creators of art. When he wasn’t fighting to import works like Henry Miller’s “Tropic of Cancer” and Vilgot Sjoman’s “I Am Curious (Yellow)” to America, he nurtured an unconventional relationship with real estate, both in East Hampton and New York City.

Here, he bought Robert Motherwell’s Quonset hut in Georgica from the artist and had plans to move Grove Press to East Hampton in the 1950s. He developed Hampton Waters off Springy Banks Road for his staff. When Grove’s move didn’t happen, he sold the land to artists and creative types.

The loft the mural currently occupies was also the former offices Rosset used for his book imprints, Foxrock Books and Blue Moon Books, a space he took up after selling Grove Press in 1986. It is also the home of Ms. Myers-Rosset, but the building is up for sale and its future is uncertain.

A conservator has estimated the cost of moving the mural and setting it up somewhere else at about $100,000. The group has reached out to the Parrish Art Museum, hoping Rosset’s long association with the South Fork and its creative community will be an enticement to take and preserve it.

Mr. Cole said that Rosset made the loft his own by “filling it with books and painting. He painted everything, even the kitchen cabinets, the butcher block, and the fridge.” The carpet was a collage of rugs. Posters from films and photographs still fill the walls and bookcases. Columbia has accepted much of the remaining archive, and Ms. Myers-Rosset was in the process of packing it away while filming took place late this spring. Although much diminished, the space still reverberated with the creative spirit of its former inhabitant.

According to Ms. Meehan, “the original thought was to do a short, edgy film, a visual poem” to the mural. Then Lorin Stein, the editor of The Paris Review, came to the loft to see a letter Rosset had written to George Plimpton before Plimpton died, but never had a chance to send. “We caught his reaction to the wall and immediately knew we had a different film.”

“We’ve gotten friends, family, and even people who didn’t know him well,” Mr. Cole said. “We chose people whose reaction we wanted to see. There are so many references.” Without giving too much of the film away, one visitor sniffed the wall, another performed a ritual to summon Rosset’s spirit.

It was on a day in mid-May that they were setting up for David Amram, a composer and musician. Mr. Amram, who is a spry 83, started out in the 1950s with mentors like Charlie Parker and Aaron Copland and eventually worked with such diverse talents as Odetta and Johnny Depp, among many others. He wrote the scores for such films as “Splendor in the Grass,” “The Manchurian Candidate,” and “Pull My Daisy,” on which he worked with Jack Kerouac in 1959.

While he did speak about what the wall meant to him, his more immediate response was to play a hulusi, an ancient Chinese flute, for his friend and the mural — “part Lascaux, part Sistine Chapel” — he had created. He noticed the pool players with skulls as faces. It reminded him of celebrations of life in Mexico and remembering the dead. “I think that one is Barney,” he said, pointing to one of the players.

“He never said what he was doing or what things meant,” Ms. Myers-Rosset said. “He would stand for hours, so focused. He wouldn’t eat or drink, just paint, stand back and look at it, and paint some more. It was enviable to see him so absorbed.” She bought him a stepladder to reach the top of the wall, and he was up on it painting until the last six months of his life.

Ms. Meehan said that to her the mural was “a map of his life” that honored free expression, both his own and that of others. Unfinished at the time of his death, it may have been a project without end, as Rosset kept changing it as he went along.

It was the same here on the South Fork, Ms. Myers-Rosset said. “He planted a forest on a half acre of land. There were trees everywhere, and he kept moving them when he saw something that didn’t quite work. You could never say to him ‘that can’t be done.’ That spurred him on.”