Gabriele Raacke: An Imaginative Approach to Painting

Gabriele Raacke: An Imaginative Approach to Painting

Gabriele Raacke, who grew up in a small village in the Black Forest near Freiburg, Germany, wanted to be a bookseller. To that end she attended the booksellers school in Frankfurt, which offered a three-and-a-half-year program required for anybody who wanted to work in a bookstore or publishing house.

“You learn about literature, everything to do with books, including the business side of having a bookstore,” she said recently in her East Hampton studio. “And after three and a half years you get tested, and if you don’t pass you have to go back to school.” Her sister had a bookstore, but it turned out Ms. Raacke never did. Africa intervened.

To those who know her as an artist who has been exhibiting her paintings on the East End for the past 20 years, it may come as a surprise not only that she is self-taught but also that she had several lives before ever picking up a brush.

When she was 19, she met her future husband, Gordian Raacke, who is now the executive director of Renewable Energy Long Island, an East Hampton nonprofit. Two years later, on a whim, they traveled together to Africa.

“The first year, we traveled for a few months and fell in love with Africa. We crossed the desert in a Citroen 2CV and we got the bug.” They made three trips there, returning to Germany when they ran out of money, then going back to Africa when they could afford to. They worked on a development project in the Central African Republic.

“With all the warfare in that region, I don’t think I’ll ever go back,” she said. “It was difficult. There were no roads, so we had to build our own. For some children we were the first white people they had ever seen.”

After a few years in Germany, they came to New York City, “with a guitar and a backpack. We were hippies. We didn’t know we wanted to live here. We had this fantasy that we would cross America.” However, Mr. Raacke’s mother purchased an unfinished loft on Chambers Street in TriBeCa and asked if her son and daughter-and-law would fix up the space. “So we built a bathroom, two bedrooms, and a kitchen. That was how we were able to stay there.”

It becomes clear very quickly in conversation that the Raackes have a longstanding tendency to do things themselves, whether it’s building roads in Africa, renovating a loft, or, eventually, building their energy-efficient, solar-powered house and studio on five wooded acres in East Hampton.

While living on Chambers Street in the late 1980s, a friend from Brazil came to stay with the Raackes. “He was a painter, and he had this big canvas. Every night he painted, and every night I watched him work because I thought it was amazing. At one point I think he got tired of me watching him, so he handed me a brush and said, ‘Why don’t you start to paint yourself?’ ”

While she worked on canvas at first, she is best known for her reverse paintings on glass. The transition began in the early 1990s with a series of glass dinner plates. She painted silhouettes of animals in reverse on the backs of the plates, then added a layer of gold, copper, or silver leaf beneath the image. Bergdorf Goodman purchased 12 of the plates to begin with, sold them, and eventually ordered more than 100.

Then a friend decided to remodel her house and gave Ms. Raacke 14 windows, suggesting she paint on them. Again, working in reverse, she started by painting the outlines of the image, then built up the paint beneath the image to get the background. The technique can be traced back to the Middle Ages.

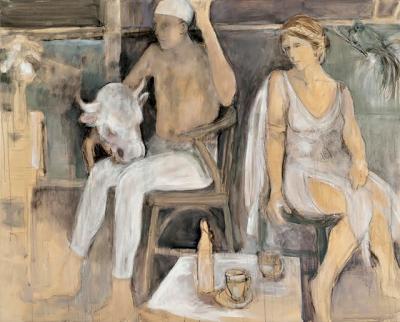

“I don’t know how to paint on canvas anymore,” she said, “because it’s just the opposite.” The fact that the paint is beneath the glass adds a luminance that can’t be achieved on canvas. Because the back is essentially an abstract painting in itself, some collectors hang them so that both sides are visible.

Ms. Raacke’s images have been influenced by her childhood memories of the Brothers Grimm fairy tales, with animals, acrobats, and circus performers figuring prominently in her work. While there is a fanciful quality to her paintings that suggests Chagall, a strong layer of surreal humor runs through the work: a flautist serenades what appears to be a hippopotamus in a tree, a pig plays a kettle drum, a cockroach walks a tightrope, a fish stands in a doorway juggling, bumblebees surround a woman whose hat and dress resemble a honeycomb.

Her portraits, too, surprise with their wit. One woman wears a crown of apples, several other figures sport sailboats on their heads, and a cat wears a necklace. Flowers and plants are another favorite subject, these so naturally unusual that they need no adornment. Whatever the subject, her use of vibrant colors and the luminosity of the glass give the works an almost ethereal airiness.

Ms. Raacke’s other passion is theater. During the 1980s she worked with several avant-garde companies in New York City, among them La Mama and Lee Nagrin’s Sky Fish Ensemble. For the past 15 years she has been involved with the East End Special Players. “When I saw them at Guild Hall, I knew they were the people I wanted to work with.”

At first she created the backdrops, then designed the costumes, and for the past few years has served as producer. Several of her paintings inspired “The Fish Juggler,” the company’s 2015 performance at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill. “The kids chose five or six of my paintings, so I had to build everything I had painted in three dimensions, large enough so the actors could go inside the houses.”

The Raackes spent 10 years in New York before moving to Boston, where they worked in a color lab, he as a photographer, she as a receptionist. After two years there, they returned to New York at the same time as Mr. Raacke’s mother decided she wanted to move to East Hampton.

While visiting her in the Northwest Woods, they began to look for land and found the wooded, rolling property where they now live. “The land was so cheap that we decided we could buy it if we built the house ourselves. We built the studio first, then the house,” which is several hundred yards away. They moved in 1998.

The south wall of the passive-solar studio is Polygal, a double-walled polcarbonate that diffuses daylight and provides insulation. During a recent visit, the temperature outside was in the 40s, but the studio was warm from the sun. The house has solar panels in addition to its passive solar orientation. Their monthly electricity bill is $5.

Ms. Raacke’s sister lives in Munich, her brother in the village where they grew up. The three siblings are close and visit each other regularly. “My mother’s family were farmers,” she said. “But I did not inherit the green thumb.” Given her do-it-yourself history, it’s likely she could master gardening if she chose to.