Nature Notes: Changing Tides

Nature Notes: Changing Tides

When I was a boy growing up in Mattituck across the bay, there were no Little League baseball teams or summer camps to occupy our time and keep us from getting into trouble. We could work for money as soon as we could walk. My first job was plucking white leghorns on my grandfather’s chicken farm every weekend come midspring. I would also mow lawns with a push mower, pick peas, rake leaves, etc., etc. You didn’t get rich but the work was fun and mostly outside. A dollar in those days would buy you a hamburger and a milkshake at the Paradise shop, or get you into four movies.

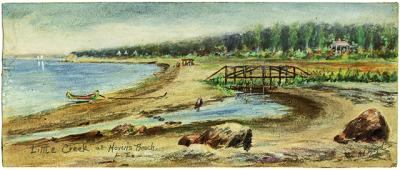

We were also clammers and fisherboys. Come early spring we would catch winter flounders as they arrived in Mattituck Creek to spawn. There were no catch limits in those days but we would not take more than we could eat or give to our neighbors. I sorely miss those times.

Come my tenure in the Natural Resources Department in East Hampton Town 30 years or so later, I began to think back on my early years. In the first years on the job I was surrounded by fishermen and fisherwomen, and it was a little like the old days growing up. The baymen with their fish traps, clam rakes, and scallop dredges scratched out enough to live on. Nobody got rich, but the fun of catching fresh stuff from the creeks, harbors, bays, and ocean was just compensation.

The late Stuart Vorpahl taught me that there were good years to catch certain species and bad years. When scallops were scarce you raked clams, when striped bass were scarce you caught porgies or sea bass. There were hundreds of aquatic species coming and going and all of them were tasty and nutritious. One of them, the blowfish, practically disappeared and then made a comeback beginning some six or seven years ago. Winter flounders, however, one of the most important fish species for baymen and one of the earliest in the season to harvest, have yet to do that.

In the mid-’80s the brown tides visited the bays, and scallops and other shellfish became scarce. The idea of growing marine shellfish and finfish to supplant scarcities came into being. It just so happened that what used to be called the Montauk Ocean Science Laboratory had gone fallow. Developers, then on the rise in Montauk, bought the buildings and property on Fort Pond Bay, an extension of Block Island Sound where it met the Peconics, to create condos. In a give-and-take procedure, the developer got his condominiums and with the help of Councilman Randy Parsons and the East Hampton Town Baymen’s Association secretary, Arnold Leo, the town saved one of those buildings, which otherwise would have been razed, and turned it into an aquaculture facility, the Montauk Shellfish Hatchery.

The town received a grant from the state to help with the conversion, which included new intake and outtake water lines, and we were on our way. The brown tide, which stretched easterly to east of Accabonac Harbor, had already crippled the scallop population, but luckily never reached beyond Napeague Bay.

Not only did we get a substantial building for free, we got the best bay water in the whole of the Peconic Estuary to grow shellfish in. We also got the wise hand of the late Anthony D’Agostino, a consummate marine biologist who specialized in lobster biology. The developer was going to raze his little lab, so we moved him into the aquaculture building.

At that time there were commercial shellfish operations on Fishers Island and in Great South Bay, and one other town aquaculture facility, that in the Town of Islip. We soon were in business and the hopes of the local fishermen were raised accordingly. The building had a long south-facing roof on one side, perfect for solar panels, and ample space outside for adding a wind turbine or two to help pay for the building’s energy needs. Unfortunately, except for Randy Parsons, the town board never got behind the energy saving idea and up till today, the building is run on standard PSEG-supplied carbon-based electricity.

Thirty years later and more productive than ever, the Montauk aquaculture facility stands in good stead under the leadership of John Barley Dunne, and the water drawn in from the bay is still plentiful and free of the colored plankton tides that have wreaked havoc with shellfish grow-out in the western part of East Hampton and all of Southampton.

Lately there is talk of a second large aquaculture facility on Three Mile Harbor. A rationale proposed for this new one is that transportation of juvenile shellfish for seeding in western town waters results in a large number of fatalities. Such losses are puzzling to me. According to one of Long Island’s most longstanding and successful aquaculturists, Robert Valenti of Multiaquaculture on Napeague, baby scallops and other shellfish can be shipped to Long Island waters for seeding all the way from Massachusetts suffering hardly any die-off. Another point with this idea that is baffling to me is the quality of the water in Three Mile Harbor.

I motor past it quite frequently and during the warm weather season the water is often colored in the same way that the water in western Shinnecock Bay and other Southampton Town marine waters are colored. It would seem that until such water is clear of colored plankton tides all year round, the method of live transport from the Montauk facility for planting in waters to the west should be improved to the point where such mortality is no longer a problem.

One other point that is troubling is the long-term fate of the baymen locally. Bay fishing largely made East Hampton the town that it is. What was in part learned from the Native Americans, e.g., the Montauketts, has been going on for more than 300 years without interruption. In my eyes there is no finer profession. Wouldn’t it be ironic if the town ended up with two world-class aquaculture facilities, but not a single bayman left to harvest their spawn.

Larry Penny can be reached via email at [email protected].