Peconic Bay Nitrogen Research Nears Completion

Peconic Bay Nitrogen Research Nears Completion

A project to determine how much nitrogen is entering the Peconic Bay through groundwater and identify its specific sources, which has been under way since fall, will conclude next month. A joint venture of Cornell Cooperative Extension, the Peconic Land Trust, the Noank Aquaculture Cooperative, and the National Grid Foundation, the findings will be presented this summer.

The effort is intended to identify specific causes of algal blooms that are harmful to shellfish and finfish, as well as to the eelgrass beds which are spawning and nursery habitat. The estuary, which contains several shellfish farms, is considered an important component of the East End’s economy. While algae blooms can occur naturally and are a key food source for some marine life, nutrient pollution, including excessive levels of phosphorus as well as nitrogen, contributes to harmful blooms.

Brown tide, an algal bloom that began appearing in the Peconic waterways in 1985, was followed by a precipitous decline in the bay scallop. And last year, the East Hampton Town Trustees closed Georgica Pond to the taking of shellfish and other marine life for much of the summer owing to a bloom of cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae.

The researchers plan a project in the Town of East Hampton, where aging septic systems and cesspools are suspected of contributing to excessive nitrogen in waterways.

Nitrogen is a primary contributing factor to the growth of algae, Kim Barbour, of the Cornell Cooperative Extension Suffolk County marine program, said this week. “More than just pointing the finger at people, we need to come up with solutions,” she said. “This project is interesting because, using state-of-the-art technology that no one else is using, we are able to track and quantify groundwater seepage coming through the bay.”

Nitrogen can enter surface waters by various means, including runoff and atmospheric deposition, but, she said, nitrogen “coming up through groundwater could be very significant to the equation.” The hope is that data from the research program will be useful in remediation efforts, she said.

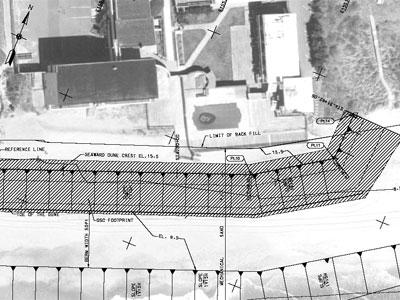

The research has been focused on the Peconic River, Noyac Bay, and Orient, Chris Smith, a natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension, said. The researchers use equipment including a trident probe, which measures conductivity and temperature. “It uses ultrasonic sound to measure flow rate at very low flow levels,” Mr. Smith said. Once a groundwater source is identified, samples of the water occupying spaces between sediment particles — are taken and brought to a lab for analysis. From there, the rate of nitrogen seepage during a tidal period, the length of time between successive high or low tides, is calculated.

An examination of land use alone would not necessarily provide a correct diagnosis, Mr. Smith said, “the reason being that aquifers are driven by gradients of pressure.” In areas where the terrain is hilly, like Shinnecock Hills, aquifers are usually associated with a lot of pressure, he said. “In flatter areas, it might barely contribute groundwater to a location.”