It took almost six years, but Adam Younes checked every conceivable box on the path to becoming a successful independent aquaculture farmer.

Undergraduate business degree from New York University, check. Graduate degree in marine and atmospheric sciences from Stony Brook, check. Aquaculture classes, check. Firsthand experience working at a shellfish hatchery, check.

Along the way Younes repeatedly heard this advice: Wherever you end up farming the sea, “you always want to be a good neighbor,” he said in an interview recently. He was told to reach out to other nearby sea farmers, fishermen, recreational users, and property owners on shore. You’ll need them, he was told. Among other things, they’ll be your eyes should something happen to your gear when you’re not around.

That’s what was on Younes’s mind last August as he was readying his equipment in his driveway in Springs, preparing to set up his operation in Gardiner’s Bay. That’s when the trouble started.

We are surrounded by water on the South Fork, but finding a site east of Shelter Island to have a small commercial oyster farm is no easy feat. Nearly every piece of water is public, owned either by the town or the state. The waters closest to shore (bays, creeks, and harbors) are controlled by the town, and East Hampton has traditionally opposed aquaculture on public waters—that is, it has, with a few exceptions, opposed the ceding of bottom and surface rights to private interests.

The only possible aquaculture sites have been in waters the state handed over to the county in 1969 precisely to develop sea farming. After an exhaustive process, town and county officials agreed in 2009 to open up oyster farming in Gardiner’s Bay, south of Gardiner’s Island, in a hook that stretches from the beach at Fresh Pond, along the shore by Cranberry Hole Road, eastward toward the old fish factory at Promised Land, and up to Hicks Island.

Younes, last year, secured a 10-acre site from Suffolk County to start his farm. Although the bay, routinely battered by the brutal northerly wind, is far from an ideal aquaculture location, he chose the most protected spot available, tucked into the southwest corner of the horseshoe curve of shoreline. Best of all, it was visible from the parking lots at both Fresh Pond and Abram’s Landing Roads, from where he could check his gear with binoculars.

On that day last August, Younes said, he was brimming with excitement. His project had been years in coming. He had poured tens of thousands of dollars in education and gear into it. He was ready: 80 floating mesh grow bags (into which his tiny seed oysters would be placed), lines, buoys, and anchors for the initial set of 100,000 oyster seed he intended for that first season.

There was one more step: The neighbors. He was keen to share the news—“I’ll have very local oysters for you in a few years!” he might have beamed—although, he figured, after all the years the county had been prepping for aquaculture in the bay, the neighbors probably already knew all about it.

The closest neighbor, the Devon Yacht Club—with its dock a distance, by his estimate, of 2,500 feet from his plot—was Younes’s first call. He dialed the main number, finding it in the phone book. It was the first and last call he made.

“They put me through to someone, I think it was the manager. . . . It didn’t turn out how I was expecting. Suddenly, I was in a confrontation, with the person asking where I’d gotten permission, and that they’d been using that area of the bay for a hundred years.”

When he hung up, everything had changed. In that brief exchange he learned that Devon, founded in 1908 and a power in the community with some 325 member families, would be deeply unhappy with his floating farm. His site was smack in the middle of their traditional sailing and sailboat-racing grounds.

“I remember feeling super alone,” Younes said. “It got into my head, and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it.” A few days later, he went ahead and set up his gear. By January, Devon had filed a lawsuit to block the county’s aquaculture program in Gardiner’s Bay. Due to a legal technicality, Younes is not named in the lawsuit, as it only challenges project activity beginning in 2017, but he’s heard informally from a Devon member that they don’t want him there, and will go after him next.

Farming shellfish for harvest has been taking place on granted bottomlands around East Hampton for centuries. It was once big business, with commercial operators both big and small, and armed guards protecting some of the plots scattered around Gardiner’s and Peconic Bays. The peak harvests came in the 1950s. But with increased criticism of mismanagement of the granted shellfish grounds, and a decline in seeding and harvests, Suffolk County was given control of most of the sites by the 1960s and, with the urging of the state, began considering other approaches to restore shellfish farming, of oysters in particular. Thus emerged the Suffolk County Aquaculture Lease Program, of which Promised Land is a tiny part.

The county began in earnest to develop its aquaculture program in the early 2000s. The intention was to give a boost to the once-huge Long Island shellfish industry and the tradition of making a living from the sea. But county officials were also driven by the promise of cleaner waters: Oysters and other shellfish improve water quality because they filter as they feed, removing nitrogen and other nutrients that promote toxic algal blooms.

After four years of deliberations—from 2004 to 2008—the county in 2009 identified huge swaths of Peconic and Gardiner’s Bays for aquaculture, 100,000 acres in all; it determined how leases would be handed out, and emphasized that the rollout would be methodically slow. The result has been a steady increase in oyster farming in the Peconic Estuary and around Shelter Island, launching—along with growers in Montauk—something of an oyster renaissance in these parts.

Farming oysters is much different now than it was in the time of the working grants. Back then, private operators like the Edwards Brothers’ Promised Land Oyster Company would buy oyster seed from Connecticut and cast it out over their grounds, the little oysters sinking to the bottom. The oysters would be left there until the grant operators returned a few years later to rake up what had not been eaten by predators, swept away in a storm, or killed by natural causes.

Some say that it is best for the environment, as far as seawater filtering goes, if oysters are grown on the bottom, and some producers still do prefer bottom cultivation, believing it to be the closest thing to what happens in the wild and that it produces a hardier shell.

But oysters grow faster in food-rich surface water in the warmer months, so today cultivators can choose from an array of surface-culture cages, racks, and mesh bags that conveniently hold them at the water line. Surface growing makes it easier for farmers to closely monitor their crops, reducing predation and die-off. In winter, the mesh bags—which the farmers in Gardiner’s Bay are expected to use—are lowered down and anchored to the bottom, away from deadly ice and the risk of damage or disappearance in a storm.

Finding a suitable location for surface aquaculture in East Hampton was difficult, but ultimately the county, with the help of designated town advisers and officials, identified the stretch of Gardiner’s Bay between Devon and Promised Land as the most suitable location.

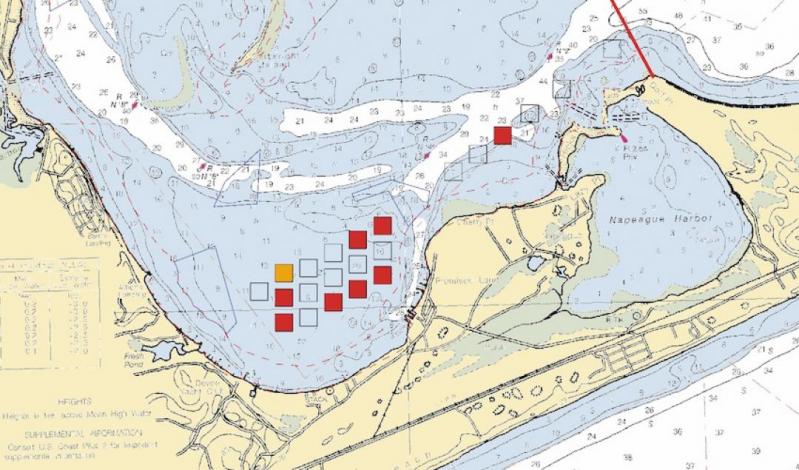

The location is made up of 22 individual 10-acre leases, with each site ringed by a 10-acre buffer, for a total of more than 300 acres in potential aquaculture. The cultivation sites will be marked out with buoys and it will be impossible for any watercraft to navigate over them. If all the leases go into operation, the floating farms would stretch from one end of this curve of shore to the other, with a channel left open between the grow sites at Lazy Point and the mouth of Napeague Harbor.

It’s astounding that a decision with such far-reaching consequences for Gardiner’s Bay could have been made seemingly without the knowledge of any adjacent property owners. But that’s exactly what happened, and it’s a key point in Devon’s legal arguments. Potentially, if all the sites go into use, not only would Devon’s sailing races be impeded, opponents say, but so would the navigation of private or commercial-fishing boats and pleasure craft.

“This plan was developed with virtually no input from recreational boaters and no consideration of these kinds of recreational uses,” said Linda Margolin, the attorney for Devon. “It’s as if they asked, ‘Where does Devon do their sailing programs?’ And then they put this right there. I know they didn’t do that, but that’s how it looks.”

Why, the club asks in its lawsuit, was the club not specifically contacted, and how could this have happened without the knowledge of its membership? The lawsuit alleges the leases would infringe on the club’s and others’ historic uses of those waters. What’s more, it asserts that the mass of sites in the bay blocking recreational uses is in violation of state environmental regulations, the aquaculture program’s own rules, and the town’s comprehensive plan.

Neighbors are not party to the lawsuit but are equally alarmed. Many ply the waters with every type of pleasure craft imaginable, and a north-south route through the lease sites is a favorite among sailboarders and kite-surfers. Upon learning that more oyster cages would be going into the bay this summer, one kite-boarder snapped bitterly, “Well, they better get ready for their gear to get vandalized.”

The county appears to have crossed all its T’s and dotted all its I’s. In 2004, it began to issue public notices, warning its proposals and meetings in The Suffolk Times. It reached out to municipalities, local organizations, and fishermen for guidance and comment, and the East Hampton discussions were reported in The Star. The advisory committee held more than 20 meetings. But most of this unfolded in the county offices in Hauppauge, which is where some public hearings were also held—so while this was an exhaustive process involving a great deal of legal precision, the bulk of the action took place UpIsland, and years ago, and Devon and its neighbors say they were blindsided. They had no idea this was coming. Not until Younes called last summer.

Along with the county’s aquaculture lease board, the Devon lawsuit names the county’s Planning Department and its director; a number of individual leaseholders who have yet to set up their operations; the Town of East Hampton, and the State Department of Environmental Conservation.

In addition to the yacht club, more than 50 residents with property nearby have signed letters of protest to East Hampton Town Supervisor Peter Van Scoyoc and County Legislator Bridget Fleming, citing the potential loss of their use of the bay for boating, paddleboarding, and kayaking and the commercialization of a public recreation area. Some homeowners also fear offshore oyster farming might hurt their property values.

“You can’t have any recreational uses of any meaningful kind with these things on the surface,” Michael Donald Patrick, one of the neighbors, said.

“Imagine what it will be like when you look out and all you see in the distance is a huge cluster of these things in the middle of the bay,” said Patrick’s neighbor, Philip Burkhardt. Like several of those who own property along the Cranberry Hole Road curve of Gardiner’s Bay, Burkhardt, it is worth noting, is a descendant of the Edwards brothers who in a previous century ran oyster-farming operations on the bay—but on bottomland, not in floating bags or cages.

The record of public comments leading up to the decision in 2009 to open Promised Land to oyster farming shows that concerns were raised about, among other things, floating equipment obstructing boating and other recreation. But county officials responded that the offshore farms would be clearly marked, day and night, by buoys and lights to prevent accidents.

“The program was vetted extensively,” said John Aldred, a member of the Aquaculture Lease Advisory Committee, and a current East Hampton Town trustee. He said there was ample opportunity for all users of local waters to voice their concerns. “There were hearings on the North Fork and the South Fork, articles in The Star.”

Brad Loewen, a fisherman who represented the Baymen’s Association at the time the location was selected—and who is chairman of the town’s Fisheries Advisory Committee—remembers: “We were looking for a place that didn’t interfere with the traditional local fisheries. That area didn’t interfere with trawling, gill netting, pound netting. The county agreed with us.”

Suffolk officials, meanwhile, are both confident that they are on solid legal ground and will win the lawsuit should it proceed, and dismayed at what they see as a lack of understanding. Although it has at its disposal some 30,000 acres countywide for aquaculture, the county is rolling out the leases at a snail’s pace of 60 acres a year, for a total of about 600 acres over 10 years countywide.

Dorian Dale, Suffolk’s director of sustainability, who also is on the aquaculture lease board, said Gardiner’s Bay isn’t the only place where shorefront owners are concerned about navigation, access, and free and unfettered enjoyment, and that those concerns are being taken into consideration.

“We are meeting with people all the time to work out concerns. But one thing in these things you can always be assured of,” Dale said, “is that everything gets blown totally out of proportion.”

Everyone seems to be in agreement that the county wasn’t being sneaky when it created and implemented its plan. Even opponents to the leases acknowledge that the officials behind the aquaculture program were guided by good intentions, and that oyster farming is to be encouraged.

But that leaves the question, What now? Will Younes be allowed to remain? Although his site is not part of the lawsuit, it likely will be part of any pretrial negotiations, and in the meantime he has too much at stake to simply abandon his farm.

“I had to file the lawsuit,” said Devon’s attorney, Margolin, explaining that the statute of limitations on the matter was set to expire in early 2018. But, she said, that “didn’t mean I’m not interested in sitting down with the county to resolve this. I have been trying for some time to do that.”

Legislator Fleming said she is working on bringing the parties together. Dorian Dale wants a sit-down, too, although he resents Devon’s claim to the entire bay.

“Read their lawsuit,” he said. “It’s like they own the waters all the way to Montauk, all the way to England, even, and it’s set down in the Magna Carta!” He added, betraying some annoyance, that the lawsuit had already had a chilling effect: Potential growers are steering clear.

Hackles might be up, but both sides are basically saying the same thing: The bays are big enough for all of us.

Opponents want the leases moved elsewhere, and the county, at least on the record, isn’t budging, arguing there’s plenty of room for everyone right there in the bay. Asked if the county would nix or move some or most of the leases, Dale demurred, unwilling to get into specifics lest he jeopardize the county’s negotiating position.

The Devon regattas and races will go off largely unhampered this summer, save for one obstacle: Younes’s little oyster farm. A state court this past winter granted Devon’s request for a halt—known in legal parlance as a temporary restraining order—to the granting of leases in the bay. Hearings to decide the next legal steps were expected in late June or July. But the two active leases, Younes’s included, were exempted from the order. The other active lease is at the opposite end of the bay, far from Devon, over by the fish factory, and it has been operating for several years.

Younes got an unfriendly call recently at the East Hampton Shellfish Hatchery where he works. It was a Devon club member, the voice on the phone said.

“Basically he was telling me to move my lease. That although I wasn’t in the lawsuit, they’d go after me.”

Although wracked by worry, Younes began in late May to pull his oyster gear from its overwinter bottomland placement and organize his surface setup for the summer. He plans to add another 100,000 oysters this season, bringing his total to 200,000. By the end of next year he could have market-size mollusks in an operation that could fetch $40,000 a year in sales, he estimates.

“But I can’t stop thinking that they”—Devon and neighbors—“want to get rid of me,” he said. “No one wants to have a farm in a hostile environment.”

“If only they’d think for a second and realize: They could have this guy and his wife, working on the water within sight of their club. We could bring fresh oysters right to their dock.”