Book Markers: 01.23.14

Book Markers: 01.23.14

For Ye of Some Faith

“Recipes for a Sacred Life” may sound like one of those self-help books that will boost your wellness best if bypassed, but in fact it’s a collection of true stories drawn from the author’s life and aimed at a subtle, everyday kind of enlightenment.

The author, Rivvy Neshama, tells of encounters she’s had that she considers touched by the ineffable — from a Viennese rabbi to an Irish woman from the Bronx, even friends and family. The ingredients include Eastern, Sufi, and American Indian spirituality, and the resultant recipes have to do with living a good life.

Ms. Neshama, who lives in Boulder, Colo., and Sag Harbor, will talk about the book on Saturday at 5 p.m. at Canio’s Books in Sag Harbor.

Changes at Permanent

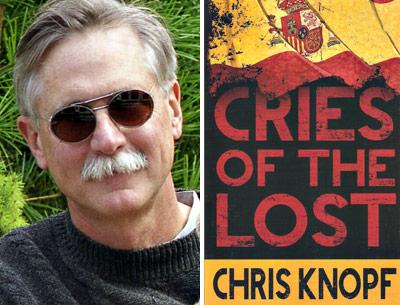

Chris Knopf’s relationship with the Permanent Press involves five Sam Acquillo “Hamptons mysteries,” his novel “Elysiana,” and two other crime titles featuring the technologically adept sleuthing of one Arthur Cathcart, the latest of which, “Cries of the Lost,” was reviewed here last week.

The Noyac publishing house’s dominant author is taking over — really taking over: He’ll be joining the owners, Martin and Judy Shepard, as a partner this year, with an eye to leading the press’s future operations when the Shepherds retire. He will continue, of course, to write.

Mr. Knopf lives in Southampton and Connecticut, where he runs a marketing and communications firm. His mysteries have won Nero and Benjamin Franklin Awards.