Through a Clear Lens

Through a Clear Lens

Think of the cold air that blew into town this week as a crystal clear lens provided for viewing the night sky, especially on Monday in Montauk, where there is virtually no ground light to interfere.

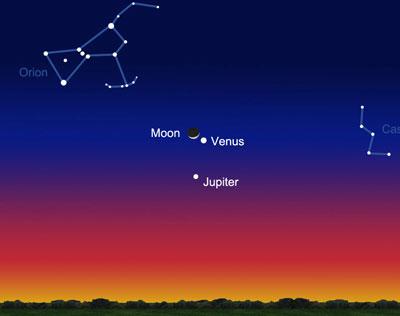

The crescent moon was bright enough to make you squint, and Venus just below and to the right nearly so. Jupiter hung directly below Venus and if one were fortunate to have a telescope or even powerful binoculars, its moons would have been visible. On Tuesday night Venus was at its farthest point from the sun.

On Sunday, April 1, Venus will be paired with Pleiades, or the Seven Sisters, a cluster of stars that in ancient time marked the start of the fishing and farming season. As it happens, April 1 marks the start of the freshwater fishing season in New York, as well as the season for winter flounder in marine waters.

East Hampton has no trout, but the Southampton Town Trustees stock several water bodies including Wildwood Lake, a beautiful place southwest of the Riverhead traffic circle toward East Moriches. Alcott Pond in East Quogue, and Beaver Dam near the Quogue-Westhampton Beach border are stocked, as well as Big Fresh Pond and Trout Pond.

Would-be trout fishermen who are not residents of Southampton must hire a resident guide, who can be contacted through the trustees’ office. “People from outside Southampton Town, non-residents, whether from Europe or New Jersey, need a resident guide,” Fred Havermeyer, a trustee, said on Tuesday.

As for winter flounder, Nat Miller, a bayman and East Hampton Town Trustee, said there was no early showing — no word that the prized flatfish had come out of the mud — despite the unseasonably warm weather prior to this week’s colder snap. “Bunkers in the bay, seals around. It was so nice last week, flowers, and now there’s frost warning this week.”

Although he said he’d already driven his trap stakes, the net will not likely be hung until about May 1. “Jumping the gun is jumping the gun. If you start early you’re not going to catch much and get the nets dirty for when the fish do arrive.”

Not so long ago, baymen including the late Francis Lester set fykes (small underwater fish traps) in Lake Montauk early and could tell you exactly when the flounder rose from their winter slumber. No one has fished fykes there in years.

East Hampton Town does have black bass of the largemouth and smallmouth varieties. Anglers may target them now — up until the Friday before the third Saturday in June — but catch-and-release only and using only artificial lures. The regular freshwater bass season begins on the third Saturday in June and runs until Nov. 30. Bait can be used to catch bass with a minimum size of 12 inches. This year, the bag limit will be five per day.