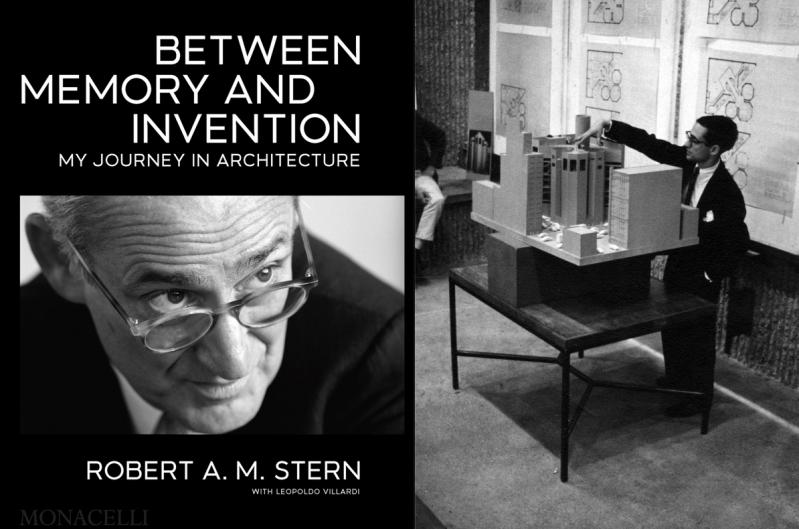

“Between Memory and Invention”

Robert A.M. Stern

With Leopoldo Villardi

Monacelli, $60

As the subtitle, "My Journey in Architecture," suggests, this is the autobiography of a career, not so much of an individual. It is also an extended essay on a philosophy of architecture, and, as such, it is of interest to buffs as well as experts. This reviewer belongs to the former category and found it very interesting.

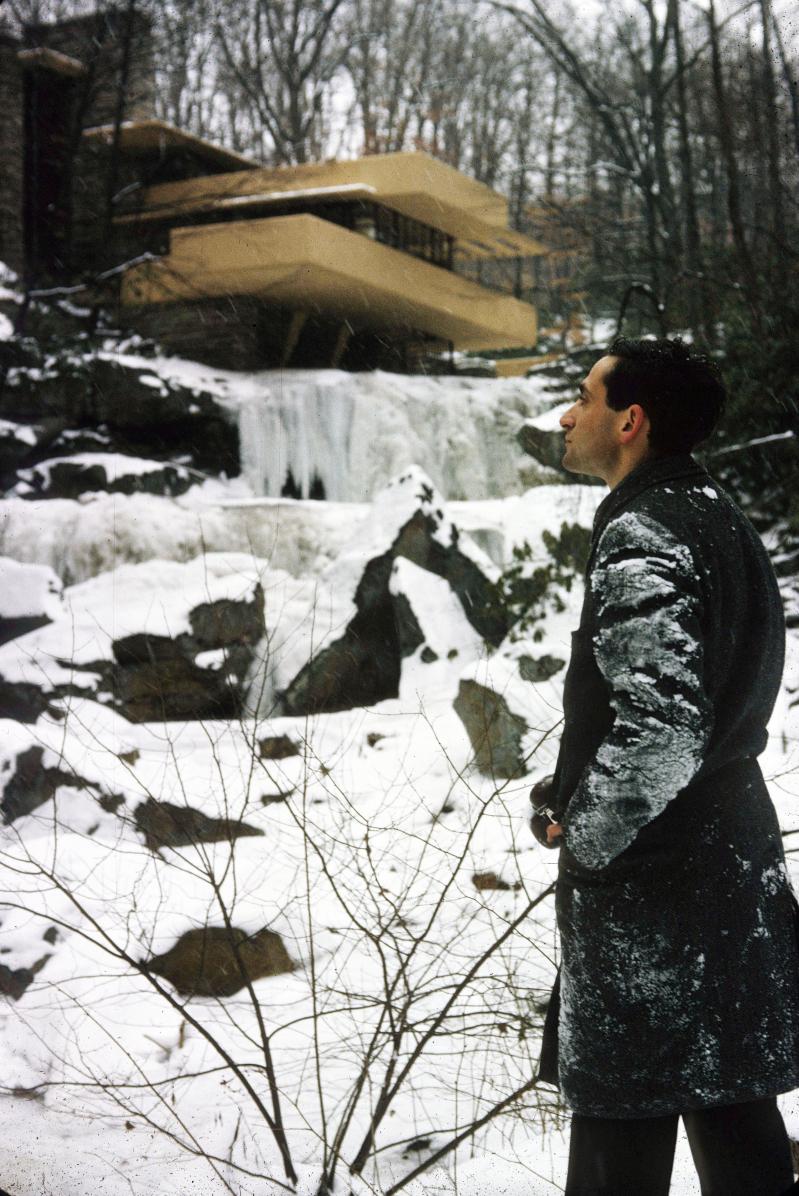

Robert A.M. Stern is a highly visible (and to some critics controversial) architect of houses, big buildings, and teaching institutions, notably Columbia and Yale. His first commissions were vacation houses in the Hamptons beginning in the late 1960s. From the start, he tells us, he was influenced by local vernaculars, which around here means the Shingle Style, which he married with modern design ideas. Throughout his career, this conception remains a constant thread woven through his work, thus the title, "Between Memory and Invention."

When Mr. Stern started out, contemporary architecture was dominated by the so-called International Style — think Manhattan's Seagram Building or Lever House — against which he would rebel. "My thesis project [at Yale in 1965] represents the beginning of my struggle to evolve an approach that would free my work from the orthodoxies of late modernism."

He also combined designing with writing books, first with "New Directions in American Architecture" in 1969. Of this he writes, "It is an opinionated work of youth, but I nonetheless stand by it, though it was written as a critic more than as an architect." Here, as in many more places — for example, "I ruined lots of apartments with weird changes that I would never make today" — he exhibits the attractive candor with which he relates his professional journey.

Another aspect of Mr. Stern's telling is his frequent allusion to influences on his work, those of other contemporaries as well as historical references. Often mentioned in the latter category is Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944), who was famous for adapting traditional styles to contemporary needs.

"[B]y the mid-1970s I was anxious to go the next step in a search for a new richness of expression in design — to put back into architecture what orthodox modernism had taken out of it." This is the movement that came to be known as postmodernism, which he describes as follows:

"The term as it came into play in the 1970s was not, in my mind, an art-historical term describing a new style but simply a convenient description of an emerging new stage of modern architecture that did not call for a naive and wholesale junking of modernity itself. Nor was it a revolutionary movement seeking to reject the recent past outright, but it urged architects to tear off modernism's self-imposed blinkers and repudiate a misconceived totalizing utopianism that, in the postwar era, had resulted in buildings belligerently unrelated to place or symbolic purpose. . . . Most significantly, postmodernism represented a return to figuration and to a sense that architecture needed to communicate, at times with frank use of ornament. . . ."

And in these words, the reader can sense Mr. Stern's passion for his convictions, another hallmark of this narrative.

He calls himself a "historicizing, contextualizing" architect. At an American Institute of Architects convention in 1978 he defined this by laying out his five core beliefs (here abbreviated) as to what this means:

1. Applied ornament is no crime. 2. Buildings that refer to other buildings in the history of architecture are more meaningful than those that do not. 3. Buildings that refer and defer to the buildings around them gain strength over those that do not. 4. Buildings that associate with ideas about specific events which caused them to be made are more meaningful than those that do not; the pursuit of specific images to convey ideas about buildings is relevant to design. 5. Architecture is a storytelling or communicative art.

Since the 1960s, Mr. Stern has had a home in East Hampton. In 1982, he produced a book "with the help of local scholar Sherrill Foster" titled "East Hampton's Heritage," which documents the Shingle Style of houses built between 1870 and the 1930s, noting that to do this he set himself to "the task of leafing through the collection of local histories as well as all the copies of . . . The East Hampton Star" in the local library. Thus, "with each new project [my firm's] understanding of the shingle style matured. At the same time, my interest in classicism grew, leading to opportunities to synthesize the two."

During the same period, Mr. Stern made a documentary series on American architecture for PBS, "Pride of Place," which marked his growing interest in preservation.

Starting in the 1980s, he and his firm began an extensive relationship with Disney under Michael Eisner to which Mr. Stern devotes a long and detailed chapter. He calls his design for the Walt Disney World Casting Center in Orlando, Fla., "a serious piece of Disney whimsy — it is architecture parlante on a popular level" — a riff on Balanchine's musique dansante, meaning that the dance is in the music. The collaborations with Eisner include Celebration, the planned community in Orlando. Its downtown, Mr. Stern notes, "was inspired by the village of East Hampton."

A late chapter in the book covers his unusually long tenure as dean of the Yale School of Architecture, which started in 1998 and lasted 18 years. Along with promoting all styles of design, he insisted that students learn to draw and use technology in creating their plans — another aspect of his commitment to integrating past and future.

About his career, he says at one point, "I have an immodest willingness to say I helped to initiate a very interesting period in architecture that was broad enough to include those who might be called 'architectural outsiders.' "

Along the journey, Mr. Stern provides amusing anecdotes and detailed commentaries — pro and con — on the work of many of his contemporaries, including much praise for the late Jaquelin Robertson, his partner in designing Celebration and the architect of the wonderful extension at St. Luke's Episcopal Church in East Hampton.

Ana Daniel taught modern European history at Southampton College. Retired from a Wall Street career as a management consultant, she lives in Bridgehampton.