In the late 1970s, Preston Powell was a D.J. who would travel to the South Fork on summer weekends to work. He’d pack 300 disco records into a drum case and wheel the 200 pounds of vinyl from his apartment on West 72nd Street to Penn Station, where he’d hop a train to East Hampton. Susan Leonard, the owner of a small club at 44 Three Mile Harbor Road called Mellow Mouth, would pick him up at the station and give him dinner, after which he’d spend the night in the dark and smoky disco, spinning until last call around 4 in the morning. Once the patrons straggled out, he’d repack his music, have breakfast, get back on the Long Island Rail Road, and head home. He didn’t mind the long day. “The energy was amazing,” he said. “I couldn’t wait to get out there.”

It was the height of disco, and while there was a lot less traffic on 27 East in those days, “the Hamptons” was already shorthand for wealth and privilege, a playground for the moneyed set. Preston was one of a cadre of city D.J.s who wanted to be a part of the new summer party. Before the Mellow Mouth gig, he hadn’t known much about the East End scene and he’d fallen for it, hard.

“It was a great time,” he said. He liked the old-money values and how understated the club felt. “It was a city crowd, but out there, in a beautiful country setting. It was a hip club, basic, but done very well.”

Powell said Leonard paid extraordinary attention to detail, curating special theme nights, like “Paris Nite Life,” and investing in what he called a “serious sound system.” She’d created a laid-back vibe in the barebones place, with black walls and a small set of carpeted risers next to the dance floor, onto which the good dancers would climb to dance. The T-shape of the building caused a bottleneck when crowds were trying to navigate between rooms. It got so hot most nights, the sliding glass doors would have to be opened to cool off the young, shoulder-to-shoulder crowd, even if it was pouring rain.

Unlike the Hamptons of today, patrons weren’t there to post about their night on Instagram, or to launch a brand, or to influence anything. They came to dance.

Love is the Message by MFSB was a hot song then, Powell said. Everyone was really into the music then. “That place used to rock. Those kids came to party.”

Blame It on the Boogie

Most people under the age of 40 today are barely, if at all, aware of just how wild and varied nightlife was out here for basically the entire 20th century. There were roadhouses with dance orchestras, a speakeasy with bootleg rum run by a famous showgirl in the 1920s, a gay-club scene in Wainscott with roots all the way back to the 1940s, and an endless parade of new discos opening and closing each Memorial Day weekend. In the ’70s and ’80s, some of the more well-known ones included Le Mans, Danceteria, Martell’s, the Hansom House, and Oceans, to name just a few.

Mellow Mouth, however, marked a unique moment in time, just before the truly big money — Wall Street money, international money — came pouring in. Mellow Mouth was the kind of place where you could walk in the door with just $10 in your pocket (not today’s $1,000 for bottle service) and everyone danced until they were drenched in sweat (no one caring about their blowout). Locals partied alongside summer people. Everyone was welcome.

The party must have been good, because, when asked, most people are a little foggy on the details. Except for one point: Everyone who reminisces about Mellow Mouth says it was so much fun. Unequivocal, inexpensive, old-fashioned fun.

During the pandemic, Kate Steinberg was feeling so nostalgic about her teen years at Mellow Mouth that she made a Spotify list called “mellow mouth mix” to share with her friends from high school. They’d get dropped off early in the evening by someone’s parents for Teen Night, every other weekend. They were 13 or 14 years old and dressed “preppy or fake preppy” in jean skirts with ballet flats or “weird little Candies heels.” Steinberg knew most everyone there, and if she didn’t exactly know a person, she said they at least looked familiar. She and her friends would dance until their feet hurt. There was a sheet over the liquor bottles behind the bar, but she’d buy a Coke for $3. “Nobody drank water back then,” she said. “It wasn’t in the beverage rotation yet.”

By the time Steinberg was 16 or 17, they would go after 11 p.m. on real disco nights where the sheet was off and booze was served. She used fake ID to get in, which was common, and then, hardly anyone blinked an eye. (The drinking age in New York State was 18 until December, 1982, when she was in her senior year at East Hampton High School.)

Diana Ross, Gloria Gaynor, the Village People, and Chic made Steinberg’s throwback playlist, and, of course, the queen of disco, Donna Summer. “All the girls would dance in a circle with our purses on the floor,” she said. “MacArthur Park would come on and we’d act out the slow part, then dance when the music picked up.”

Steinberg, who now lives in Brooklyn, remembers the place being “undesigned” and having a disco ball that would sparkle when the disco lights came on throughout the night. “It wasn’t nice,” she said. “But I loved it.”

Victoria Brown used to arrive at Mellow Mouth with a friend, wearing nearly matching outfits, and dressed ready to dance. “My mom took me to the mall and got me a blue, long-sleeved, Danskin leotard with a sparkling metallic sheen, and matching skirt with a flounce on the bottom,” she said. “It was 150 degrees in there, but nobody cared.” She remembers the club as being unintimidating, welcoming, and exciting. “In a way it was a sweet slice of what was happening in Studio 54 in New York for us dopey young teenagers,” she said. “Even though there was no drinking, it still felt sweetly forbidden. Like we got to do this thing. Inhibitions were put to the side.”

At 18, Clair Libin was saving money for college as a cocktail waitress at Mellow Mouth, making $4 minimum wage. She had to kick her way through the crowd on the dance floor so she didn’t spill her big tray of drinks. “It worked,” she said. “They were high and oblivious because they were in the music. My hands weren’t free and they were busy dancing.” She said she had no clue what she was doing — and didn’t even know how to pronounce the name of the Russian vodka people were ordering. It didn’t matter: She was young and cute and got great tips, a point not lost on one co-worker, who happened to be Grace Jones’s brother. “He was always annoyed with me when we tallied the money at the end of the night.”

“It was before AIDS,” Libin said. “Lots of drugs. A lotta sex. The Women’s Movement. It was a really great time. Everyone was feeling free and wanted to have fun.”

East Hampton was different, too. “It was a real place. There were real stores. There was a candy store. A musty-smelling hardware store with toys upstairs. Mellow Mouth was filled with regular people. People could afford to go out then, nothing like now,” she said. “By the late ’80s and ’90s, people with money started coming out, complaining about noise.”

Disco Inferno

Unsurprisingly, Mellow Mouth, like most of the clubs back in the day, had its share of noise complaints and trouble. There were fire-code violations that involved the courts and fines, and the police were called in over reports of fights on a fairly regular basis. One fight involved the swinging of a three-foot ax. Once, the police were called because a man was sitting at the bar drinking his beer with a shotgun on his lap. In 1976, right after Mellow Mouth opened, a Bible college student wrote a letter to the editor of The East Hampton Star complaining about the “nauseating display of those lips” in the club’s lipstick-kiss mouth logo.

If Mellow Mouth was the height of affordable fun, the Jag, with its zebra motif, was the inflection point to another kind of nightlife and another kind of Hamptons. The Jag opened its doors in the former Mellow Mouth space at 44 Three Mile Harbor Road in 1984. The customers became a little more well-heeled. The Ferraris and Rolls-Royces had arrived.

Tony Cerio, who was one of the owners of the Jag, described that time as “on the brink.” The Hamptons was changing, he said. “Back then, it was a whole different temperature. Everybody knew everybody. There were no airs.”

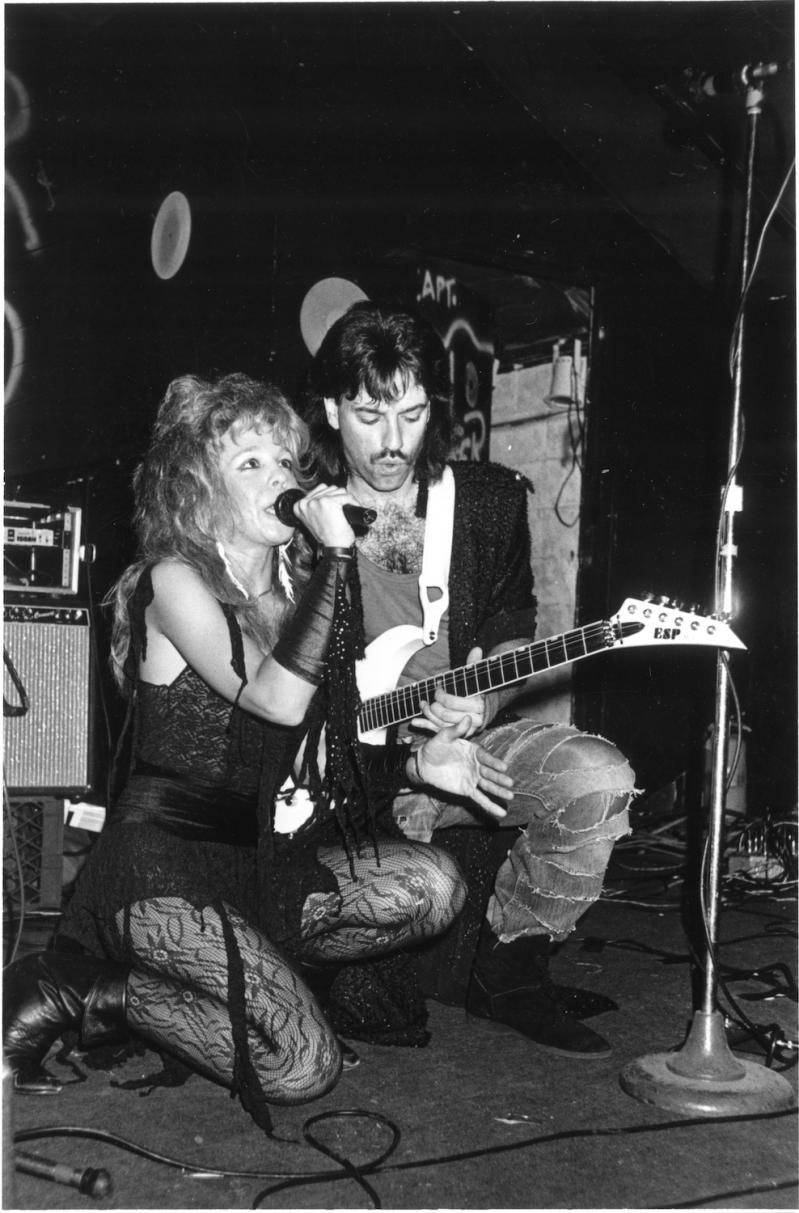

Everyone danced their faces off at the Jag, too, but live music was its big draw, including the likes of Iggy Pop, who brought in $25,000 in one night, and the Ramones. The club got so popular its managers had to build barricades around the stage.

Legally, the Jag had a 250-person capacity, but some nights 600 or even 700 reportedly packed in — with hundreds more standing in the parking lot trying to hear the music through the walls. More and more celebrities showed up to be part of the crowd, alongside the old mix of South Forkers and city people: Eddie Murphy, Too Tall Jones, and David Keith, among others. The vibe, as with Mellow Mouth, was fairly epic.

Brown saw A Flock of Seagulls at the Jag, and glimpsed a bit more of the new wavers than she had bargained for: “I was walking through the parking lot to meet my dad, who was picking me up,” she said. She passed the band’s tour bus with its interior lights on and got an eyeful of the half-naked band changing out of their stage clothes. “I was startled. I couldn’t quite believe what I was seeing.”

The Jag was popular, but it was during the Jag years that 44 Three Mile Harbor Road first became associated in the minds of local people with some really bad, dark memories. A high school girl named Tracy Herrlin left the club at 2 a.m. one night and was murdered by an acquaintance. The incident shook the small town and became intertwined with any reflecting on the era. Folks relishing the happy memories from those days don’t do so without also talking about how unsettling Herrlin’s murder was for them. Her murder wasn’t the only tragedy at 44 Three Mile. Later, a beloved former East Hampton High School sports star named Kendall Madison, who was promoting an event at the space in 1995, died after being stabbed in the parking lot at the age of 21. Nothing really good seemed to happen there after that.

When news broke this spring that the property’s current owner wants to raze the building, a lot of people — older people, those who remembered — said they’d be glad to see it go.

Shadow Dancing

The definition of party in the Hamptons has shifted over the years, the changes driven by many things. Mostly money. Buckets and buckets of it. Fame, too. Celebrities used to escape to the East End to avoid the spotlight, but eventually they began racing out east to bask in it. Everything became a commodity as the curtain fell on the 20th century: not just actual real estate, but place names, bragging rights to localism, square footage on the beach, even telephone-number exchanges. This cultural shift paved the way for the glitzier club scene of the ’90s, where velvet ropes became an every-night thing and the lines guarded by bouncers grew longer. Clubs like JetEast and Life at Tavern didn’t have V.I.P. sections–the owners described the club’s patrons as entirely V.I.P. Fun, as the

Hamptons knew it, evolved. Or devolved, depending on who you ask.

The days when a group of college kids or 20-somethings from Manhattan could rent a summer place — make some cash waiting tables, and spend nights at a disco — are over. Regulation might have started the decline of the share house, but the pandemic was its death knell. Young people are all but priced out of the East End these days.

Sarah Rehm, age 24, is a dancer by profession and she has only heard about dance clubs from her parents. They talk about how places like that no longer exist. “There’s nowhere to dance,” she said. Nowhere affordable to have fun on the East End either. She lives in Holbrook. Her Hamptons experience today requires intense research and mostly off-season visits. For her 24th birthday, she, her brother, and some friends rented a condo in Montauk for two nights. “Because of the cost, we decided to cook in one night,” she said, “We researched to find a burger that was $20, not $40.” They researched an affordable place to hang out after dinner, too, and ended up at the Stephen Talkhouse, where the cover that night was $10. (Of course, when a hot band is playing the Talkhouse, the price of entry goes up to $100 or more.) Given the cost of the South Fork, the North Fork is where Rehm and her friends will be heading for fun this summer.

“Employees nights” — or “industry nights” — were a big thing among young people in the ’90s. “It was affordable,” said Heather Wyatt, whose family has had a house in East Hampton for three generations. She remembers hanging out at 44 Three Mile Harbor when it was Diamond Lils, once with a group of people that included Jerry O’Connell “before he was anyone.” She and her friends would go there or to Oceans in Amagansett at least twice a week.

Wyatt and her friends always worked summer jobs, as kids did then. She used to save for college with her tips from the Lobster Roll, collecting envelopes of cash to carry her through the year. “The party didn’t even start until midnight,” she said. “You had to go home and shower after work.” She’d wear her pin-straight hair down and dance until 4 a.m., not caring that it got soaked. “The next day, we’d wake up and go do a double.” Wyatt said.

“Everyone has internships now,” she added, somewhat ruefully.

“The vibe was killer back then,” said Cerio, the Jag owner. “It was a whole mess of wild moments and craziness. It was fun and I looked forward to going to work. After a while, it wasn’t anymore.”

The Jag might have lasted the longest in the 44 Three Mile Harbor space. It was probably also the building’s last real hurrah. Eventually, it started losing money. “It went downhill. Everything changed. Drinking changed,” Cerio said. “It got hard.”

Daddy Cool

Powell loved his East Hampton deejaying days so much it gave him an idea. He, another D.J. named Viviano Almonte, and Joann Lara had vision. They saw the untapped opportunity that was the late ’70s on the East End, so, in 1981 they bought a roller rink called Neros in Sag Harbor and in 1982 opened, eventually turning the space into a much talked-about new music venue: Bay Street. The space was originally a Grumman airplane factory. “It was a huge 10,000-square foot loft warehouse,” Powell said. “Occupancy like that was unheard of out there. Mellow Mouth was more like a warm, house party by comparison. Intimate, like all your friends. All here to party.”

Between 1986 and 1989 the club saw its heyday. Billy Joel, Simply Red, Tina Turner, Madonna, and James Brown played at Bay Street, plus Sunday Reggae on the Wharf was a huge night. The club drew fans from all over to the village, which was then still less crowded and less expensive than other neighboring hamlets. On big concert nights, the hotels would sell out and the restaurants were packed. “We were reasonably priced,” Powell said. “We were the spot for live music out there. But then the ’90s came, it got more commercial, and showy. It got glossier.”

Plus, the village and township were tightening rules, and trying to shutter the place. After 10 years, Powell, facing another lease, saw the writing on the wall. He decided to close Bay Street, and, along with it, a chapter in the party history of the Hamptons. He looks back on those days fondly. “We put Sag Harbor on the map.”

Don’t Leave Me This Way

As the price of everything went up on the East End, what happened after dark became part of the marketplace—a commodity — too. Everyone and their mother started a charity, and pricey galas and then auctions took over the social scene. Instead of art openings at which bohemian painters and poets did improvisational modern dance on a lawn to the sound of jazz — instead of fund-raisers with a $100 ticket cost — there were $10,000 tables and “step-and-repeat” photo ops every night. The publicists arrived. Getting press suddenly drove everything and people showed up to be seen and photographed.

Perhaps one of the most notorious pivot points in the Hamptons party scene happened when Lizzie Grubman, a Manhattan publicist, had a verbal spat with a bouncer at the now-defunct Conscience Point club in Southampton, then threw her Mercedes S.U.V. into reverse and ran it into a crowd, injuring 16. It would be hard to imagine a more cinematic representation of the beginning of the end.

East Hampton is now, officially, according to Forbes and Fortune, the playground for the ultrarich. The uniform is practically official too: white jeans and Loro Piana loafers, a bottle of rosé in hand. The party is sitting around a dinner table (inside because, mosquitos) being served by a private chef. Instead of tequila shots, someone is passing around gummies.

Dancing, for the most part, died. The East End seems to have developed an inverse relationship between having money and having nightlife fun, where sadly, you can’t have one without a whole lot of the other.

If These Walls Could Talk

The owner of 44 Three Mile Harbor Road, Cilvan Realty, has made several adjustments to its plans to build a mixed-used structure for retail, housing, and more, but after multiple hearings with East Hampton Town’s Planning Board and Architectural Review Board — plus a fair amount of neighborhood outcry — approval is still pending as of press time. But the history of the old roadhouse is eye-opening. Here’s a decade-by-decade look back at more than a century of jitterbug joints and red-hot discos.

1910s

Whether or not the original building was once a potato barn — as a later owner speculated, based on its design — is lost in time, but by 1910, a grocery store is being run here. Perry White, known around town as a “courtly” waiter at the inn later known as the Maidstone Arms, is the proprietor, opening it for his son to run.

1920s

The grocery store goes out of business. The first roadside restaurant opens on the site.

1930s

Roma’s Inn opens its doors — a year-round “Dance and Dine” night spot with music and a floor show with chorus girls. Palma’s Tavern follows, in 1938, with food (“Chow Mein and Chop Suey a Specialty”), swing dancing to live music from Seller’s Greenport band, and a bowling alley.

1940s

During the war years, Palma’s Tavern holds “Service Men’s Night” on Mondays, giving huge crowds of Navy and Air Force men free sandwiches, cakes, pies, and beer. Around 1943, Peter Fedi, a groceryman who owns commercial property on nearby North Main Street, buys the building and opens Fedi’s Tavern, advertising “Pizza Pie, Soft Shell Crabs, Steaks and Fine Foods.” After dark, Don Reutershan and His Orchestra serenade the diners. In 1948, a pair of brothers calling themselves “the Tango Boys” start managing the club, “Pete’s Tavern,” though it will still be owned by Fedi into the 1960s.

1950s

The Harbor Club opens its doors, boasting an air-conditioned dining room, cocktail lounge, and a menu that is a combination of Italian and Chinese dishes. There is dancing three nights a week to the sweet sounds of the Bob Ellis Trio (“direct from the Hotel Plaza in New York”). In 1958, plainclothes detectives catch Bill Leonard, Fedi’s business partner, selling “gin and orange juice” — called a “screwdriver” in those pre-vodka days — to high school students. No one seems particularly outraged.

1960s

A decade that begins with dine-and-dance and ends with disco. There’s the Supper Club, and, in 1965 a realtor named Joseph Luciano opens Fontana d’Notte, an Italian restaurant offering after-theater dinner specials and “the fountain lounge.” Fontana closes in 1967, and a club called the Laughing Stock takes its place, with dancing seven nights a week. There are beatnik evenings of poetry readings and “Paco’s Paella.” By 1968, the word “discotheque” enters the lexicon in Laughing Stock ads. On Fridays, “Eugene’s East” nights heat up the Laughing Stock scene and things are getting wilder, with “Political Cabaret,” a rock band called the Aluminum Dream, and Arthur Hertzog — author of The Swarm — “as ringmaster.”

1970s

In 1971, Richard Polo opens a night spot called Polo, with a distinct group-house-singles slant: “After a hard day at the beach, come to POLO. . . . Bring your whole house. Or come alone and meet someone here and establish a meaningful relationship.” In 1973, Patricia Fabry Smith — onetime circus performer and impresario of popular “women’s bars” in Manhattan and Provincetown — transforms the space into Patchez, a restaurant and gay bar. Celebrities come. Ads for Patchez in The Star tout “the only female chef in the Hamptons.” In 1976, Mellow Mouth Club — which began life as the colorful “Mellow Mouth Nice Cream Parlor” in Amagansett — opens at 44 Three Mile Harbor Road. Through the high-disco years, Mellow Mouth, with its red-lips logo, reigns. It is open all year. On Tuesday nights, singles are invited for “backgammon, rap sessions, and dancing.” On weekend afternoons, it’s Teen Disco.

1980s

Disco nights give way to a crowded concert scene. For a time, the club is called Hurrah. Next, it becomes the Jag, which is less disco, more New Wave, and has a four-year run with performances by Flock of Seagulls and Men at Work. Lobster A-Go-Go follows, with a similar formula and major acts, including Iggy Pop and the Ramones.

1990s

It’s Lil ’s restaurant for a while, then the Moschetta family, who have owned the property since the 1970s, opens a restaurant called Kristie’s, specializing in brunch on the patio. Things are relatively calm, and then Danceteria — Hamptons edition of a legendary New York Club — opens in 1995. Hopping again. Cilvan Realty buys the building in 1998 and NV Tsunami kicks off

2000s

Before being busted, in 2000, a conman posing as a Rockefeller frequents NV Tsunami, rubbing shoulders over sushi and Veuve with the likes of Sean (“Puffy”) Combs, Billy Joel, and Donald J. Trump. After Tsunami closes, another round of pretenders (Resort, the Pink Elephant, Le Flirt, and Kobe Beach Club) keeps popping up, blazing for a weekend or two — attracting TV and music stars famous enough to appear in paparazzi photos in the gossip websites — then fizzling out. Many are eastern outposts of Manhattan boîtes.

2010s

More clubs with expensive bottle service, a smattering of celebrities, and a short life span: Lily Pond Restaurant, SL East, Finale, Club Philippe (or “the Club at Philippe,” run by Philippe Chow, which lasts a couple of years), and the Leo. Is it possible the internet has killed off club culture? In 2019, the Spur co-working space in Southampton tries to win customers by converting the building into the Spur East, but co-working doesn’t catch on. The sign remains out front for ages.

2020s

During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, it’s briefly a last-chance, drive-through discount wine and liquor store; customers order from a laminated menu. In 2021, Club M A R S opens. “It’s Mars, like the planet, it’s a different level. It’s a nightclub, dining room, and a garden that will [be] like Tulum style on Mars,” its impresario, Ivan Busheski, tells Page Six. It’s gone by 2022, when El Turco, an offshoot of a well-known Miami Turkish restaurant, opens. As of press time, the doors of El Turco had reopened at 44 Three Mile Harbor Road, but its future remained uncertain.