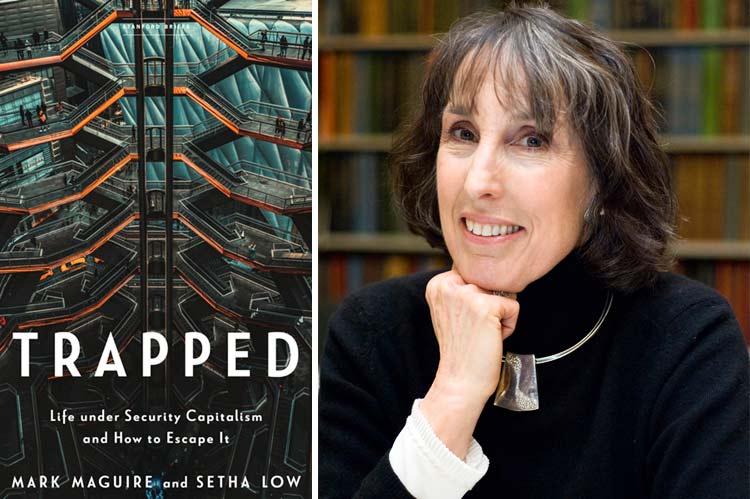

“Trapped”

Mark Maguire and Setha Low

Stanford University Press, $14

There is no doubt of the topicality of “Trapped: Life Under Security Capitalism and How to Escape It” by Mark Maguire and Setha Low.

In the time it took to read the book, the following occurred: gun rampage in Somalia (despite high security), bloodbath at a Russian concert (despite surveillance video and reportedly a U.S. warning), police officer killed in Queens, fatal subway shoving at 125th Street, and parents of students at the University of California at Berkeley hiring private guards to patrol the campus perimeter at a cost of over $40,000.

As Mr. Maguire and Ms. Low write, “Security is everywhere these days; thus, it is everyone’s problem.”

But the security problem examined in “Trapped” is not an elevated risk of personal harm, which the authors maintain does not generally exist, at least not in the United States. Rather, the authors want us to stop indulging fear — and allowing others to manipulate it — in ways that promote a society that is overgadgeted, overmilitarized, and oversurveilled, but less just, less cohesive, more segregated, and no safer than before today’s widespread reliance on the products and ideology of “security capitalism.” The authors explain that they prefer this term as broader than the previously coined “surveillance capitalism.”

In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, Congress passed the Patriot Act, which permitted greater government surveillance of individuals in the name of counterterrorism. “Trapped” focuses on how the private sector has piled on, including security companies, university researchers, and so-called security experts for whom, alarmingly, real public safety may be neither a skill nor a goal.

The book explores “middle-class complicity”; how individuals uncomfortable with risk have enabled the concentration of power in the security industry, which the authors define to include policing, given the increasing “privatization of many aspects of contemporary policing, swaths of the criminal justice process, and a significant portion of the prison system.” The authors cite an estimate that in the United States, “private guards outnumber police by a ratio of 3:1.” According to “Trapped,” in 15 states private guards are not even required to receive training to carry arms.

Ms. Low is distinguished professor of environmental psychology, geography, anthropology, and women’s studies at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. Mr. Maguire is professor of anthropology at Ireland’s Maynooth University and has done much field study in the area of international security. Though their subject is complex, the authors have produced a slender, highly readable book that packs a big punch. Using what they term “ethnographic” essays, they illustrate their points in chapters with provocative titles such as “Counter Counterterrorism” by describing places and people, mostly from the United States and Europe, including disillusioned security professionals.

For example, they describe a hard-working airport police inspector/training manager in Great Britain who had implemented community-policing techniques inside the airport, speaking regularly to “passengers, airline staff, drivers, cleaners,” and other workers. This “constant engagement with the community” had tipped him off to at least one incident in time to prevent it. Yet at a workshop sponsored by a global technology company, he found himself dismissed as a mere “end user” for the participants’ surveillance and futuristic wall-moving offerings, not someone who had anything of value to teach others based on his experience and successful record. Eventually, he changed professions.

Yet, according to the authors, human-centered tactics are the ones that work and should be expanded, not the quick but largely ineffectual fixes that the authors label “solutionism.” They cite research that more inclusive and egalitarian practices, especially knowing one’s neighbors, correlate strongly with feelings of safety, and while people want actual safety, feelings are vitally important because “the potent emotion of fear” drives socially detrimental behaviors.

One such trend, especially for many white, middle-class people, is the urge to isolate in gated communities. On Long Island, the authors note, the number of gated communities has increased from approximately five in 1996 to 40 in 2022. Nationwide the number of households/units in “secured communities” was 11 million in 2015, also a substantial increase from the 1990s.

According to Mr. Maguire and Ms. Low, gated suburban communities are no safer than others despite their guards and security cameras, which only serve to “reinforce perceptions of threats,” putting fear front and center in daily lives and stoking the demand for more “security.” At the same time, such communities have adverse impacts, “diverting resources, and contributing to racialized segregation and societal fracturing.”

In their fascinating chapter about New York’s Hudson Yards development, the authors portray it as an ultra-expensive, glitzy gated community built on public land with public subsidies in the form of large tax breaks, raising troubling questions about classism, racism, privatization of public spaces, and the future of image-conscious, financially strapped cities.

The behavioral expert and law professor Cass Sunstein has written of “habituation,” the human mind’s tendency to accept small changes with relative passivity. Habituation can be dangerous, allowing us to accept a series of incremental changes that would not be tolerated if delivered as one big change. “Trapped” is a disconcerting, anti-habituating read, suggesting that too much power has already been ceded to private security interests that are not accountable to the public.

Do we want to be “end users” of security offerings, or citizens of thriving communities? Mr. Maguire and Ms. Low say it is not too late to choose the latter. But to do that, we have to resist the “desire to pull away from everyday risk and the noisy chaos of social relationships.”

In other words, if you do not know your neighbors, maybe this weekend would be a good time to knock on their doors.

Marian E. Lindberg is an attorney, writer, and conservation professional who lives in Wainscott.

Setha Low lives part time in East Hampton.